Returning Zorn to Boston: An Anders Zorn talk with Dr. Johan Cederlund

Zorn Museum Director Johan Cederlund delivered a lecture on renowned 19th Century Painter Anders Leonard Zorn at the Scandinavian Cultural Center in Newton, MA.

Reaching the end of the grandeur of Renaissance Italian masters in the Raphael Room of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, one will find the Short Gallery. Amongst the various contemporary paintings displayed is a glowing portrait of Isabella Gardner in her trademark string of pearls. Portrayed in front of the renowned Venetian Grand Canal at night, the obscure background heightens the luminosity of Isabella in her white dress, which in turn accentuates her soft facial features, the dramatic effect of the flunging-open of the doors, and her elegant composure. The noticeable fireworks at a distance provides the spectators context to her excitement. The creator of this piece was Anders Leonard Zorn, a Swedish artist and friend of Gardner’s whom she remained in correspondence with until his death in 1920.

On April 11, Dr. John Cederlund from Sweden’s Zorn Museum delivered an animated lecture called “Anders Zorn – Sweden’s Master Painter” to local art lovers in the Newton area. The event was hosted by the Scandinavian Cultural Center in Newton in partnership with the The New England Chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art and Swedish Womens’ Educational Association. Dr. Cederlund has been the Director at the Zorn Museum in Mora, Sweden since 2006. Prior to taking the position, he was Chief Curator at the Uppsala University Art Collections. He also serves the position as a Royal Chamberlain to the King of Sweden, a role he has held since 2016. Many of his books have been translated into English, including “Anders Zorn – Sweden’s Master Painter” (2013) and “Classical Swedish Architecture and Interiors” (2007). With this lecture, he hoped to bring Zorn’s popularity back to the States.

At the turn of the century, Anders Zorn was one of the most well-known Swedish artists in the United States and around the world. He was not only a talented craftsman, but also a calculating businessman, never neglecting chances for commercial success. When his paintings garnered massive attention in Chicago, his first response was to call home to Sweden to ask for more of his paintings to be sent to the States to be commercialized. Today, greater attention is placed on Zorn’s contemporary, Carl Larsson, for the latter’s tranquil pastoral images featuring folk cultures better fit the stereotypes of the Swedish identity. Thanks to popular culture depictions, one’s impression of Sweden can hardly stray from a Larsson-esque country house of pastel hues in the midst of vibrant plants. Nonetheless, Zorn’s influence on art can still be seen omnipresently. Frida Kahlo was known for collecting Zorn’s etchings, and Zorn’s own works are still widely exhibited across the east of the United States.

Born 1860 in a pastoral village of Mora, located in the midwest of Sweden, Anders Zorn was raised by his grandparents on a farm. Though the artist traveled around the world, the rural scenes had remained an omnipresent motif in his craftsmanship, like many of his contemporaries. He was artistically trained at the Royal Academy of Arts in Stockholm where he was known by his peers and instructors as an immensely talented prodigy with incredible potential.

In 1885, he married Emma Lamm, the daughter of a Jewish merchant family in Stockholm. Despite his artistic success in Stockholm, Zorn was troubled by the disparity between their respective social classes; therefore, most of the four-year engagement was hidden from the public. After their marriage, the Zorns traveled extensively around the world, well-funded by Emma’s family. In Europe, Zorn quickly made a name as a portrait painter. In Paris, he painted portraits for wealthy Jewish families, introduced through the Lamm’s connections. Their stay in Paris inspired Zorn in two ways, initiating oil painting and Impressionism.

Zorn's depiction of moody lighting is notable in "Summer Vacations", a watercolor painting.

Like other artists in Paris, Zorn began to experiment with oil painting. While Zorn’s watercolor pieces depict sophisticated illumination — almost resembling the effect of oil colors in its opacity — oil painting allowed him to dramatize the contrast of light and dark. In France, the experimental style of impressionism began making its way to Parisian salons through expressive strokes and bold use of colors, pioneered by Claude Monet and Vincent Van Gogh. Nonetheless, they were yet to gain mainstream success. “I wouldn’t say that [Zorn] was an impressionist. No,” Dr. Cederlund pointed out, “he is more of a Naturalist. Juste-Milieu.” “Juste-milieu,” meaning “middle way” in French, refers to the artistic style that found the middle ground between the radicality of impressionism and the traditional. The “juste-milieu” artists experienced the most commercial success, and Zorn was one of them.

Zorn thrived artistically, socially and financially in Paris. “Talent like Mozart, success like Napoleon,” Cedurlund said of the artist. As he garnered more success internationally while in France, Zorn became the envy of many other Swedish painters. Nonetheless, Zorn’s name and work did not reach the United States until his encounter with Isabella Stewart Gardner at the 1893 Chicago World Fair. Zorn’s 1892 work “Omnibus,” depicting a Parisian metro crowded with people, attracted the attention of the renowned Boston art collector.

After becoming fast friends, Gardner invited the Zorns to join her on her trip to Venice. “Like many female tourists to Venice, Isabella fell for a good-looking gondolier,” Cederlund joked, “and she asked Zorn to paint him.” Zorn did, “but only from the behind.” The majority of the image is dominated by the back of a gondolier; at the far end, another gondolier lifts up his head towards the direction of the first gondolier, seemingly creating a correspondence. “Perfect composition of a dialogue,” described Cederlund of this painting.

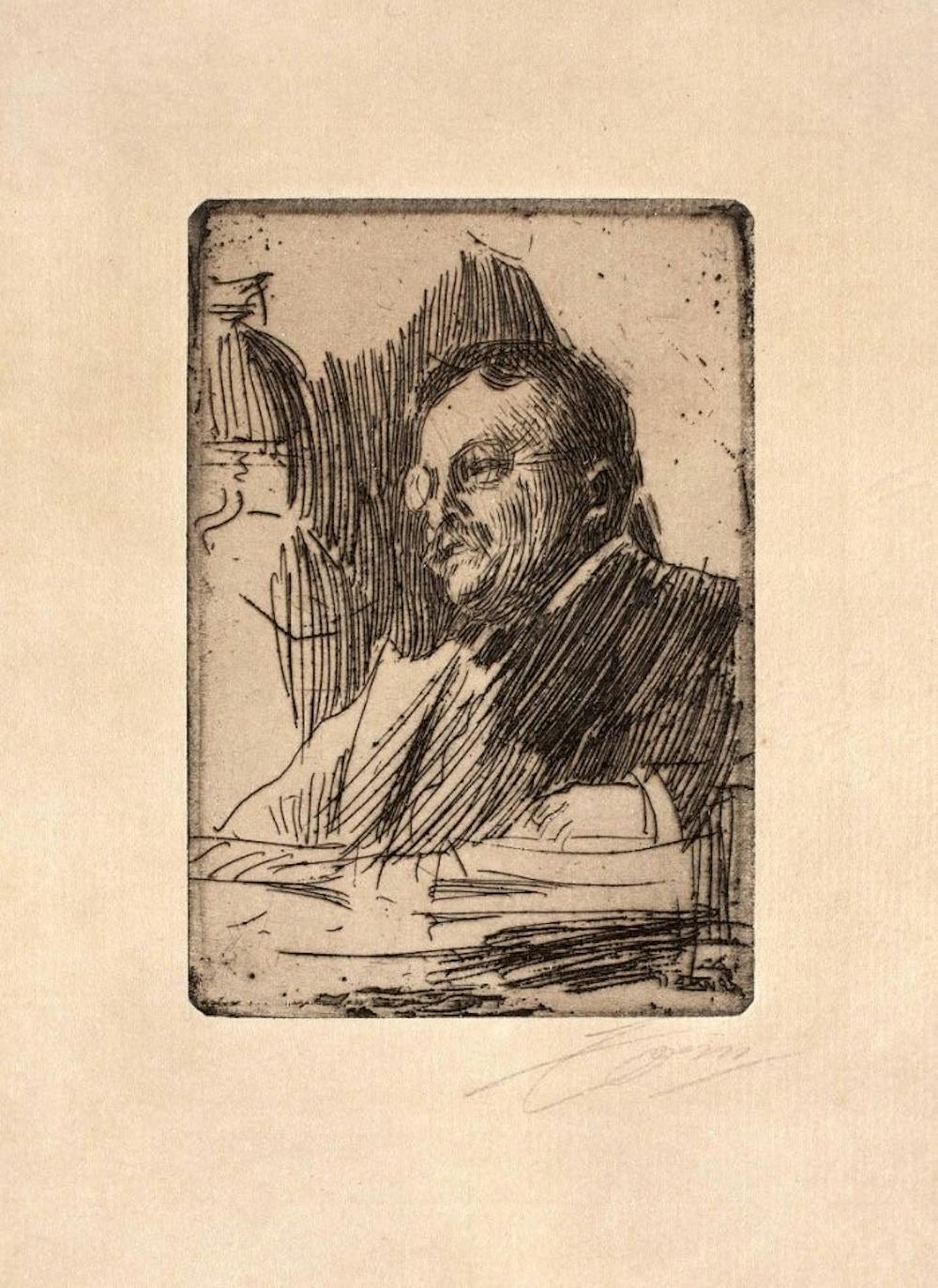

In the United States, Zorn’s name was heavily publicized due to his friendship with Gardner. In a total of seven visits to America, Zorn received commissions to create etchings of three US presidents, Taft, Cleveland, and Roosevelt, and multiple influential figures in the American upper-class social circles. Today, “Omnibus II” is displayed in the Gardner Museum.

Dr. Cederlund was keen to stress that Zorn employed a variety of mediums for his artistic creations, including oil painting, watercolor, etchings, and sculptures. The watercolor and oil paintings of Zorn capture fleeting moments, appearing to be done in an uninhibited manner, as was the fashion of the time. Nonetheless, x-ray scans revealed that underneath the watercolor pigments of his paintings were in fact careful outlines of thin oil paint strokes as well as layered remnants of painting — suggesting corrections — overthrowing the notion that the paintings were completely without any drafting.

One tale Cederlund brought up to underscore Zorn’s unconventional process was an 1886 painting, “Törnsnåret” (The Thornbush), currently on display in the Zorn Museum in Mora. The Zorns were traversing through the woods on the island of Dalarö in the Stockholm archipelago when his wife’s dress got caught in a thorn bush. Rather than helping his wife free herself, Zorn sprinted home to grab his water paint and materials to depict the moment. Emma complained of being bored, stuck in the thorn bush as Zorn carefully and slowly painted the scene, so Zorn returned with a girl for Emma to talk to to keep her company, whose figure is visible at the far left of the scene. Take it from poor Emma’s personal experience, the appearance of a rapid completion of Zorn’s paintings through expressive, bald strokes is a mere illusion.

“Etching” is a production technique that consists mainly of designing illustrations on a waxed metal plate which later inked to be compressed onto wet paper — a lengthy and tedious process. While having learned to manufacture etchings in his schooling years at the Royal Academy, Zorn did not put it into use until very late in his artistic career. He showed a natural talent and immense passion for the practice, collecting and finding inspirations from the etchings of Rembrandt. Nonetheless, he was ambivalent when it came to a preferred medium to work with. Cederlund concluded as he showcased a number of masterpieces completed in different mediums on the displayed slide, “He believed that ‘All good art is about craftsmanship.’”

From the Zorn Museum of Mora, Dr. Cederlund’s lecture “Anders Zorn – Sweden’s Master Painter” returns not “Zorn” to Boston, but context to his pioneering reputation as a Swedish artist abroad and the retelling of stories that made him a significant master of art in this city. One hundred years after his death, the name of Anders Zorn is remembered in the city of Boston as a friend of Mrs. Gardner, but the talk reminds us that at the turn of the previous century, he was a national pride of Sweden. As Dr. Cederlund remarked at the beginning of his talk, “He was damn good. Absolutely the star.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.