EDITORIAL: University protest regulations endanger activists

This year’s Student Rights and Responsibilities handbook laid out new and more restrictive guidelines on student protests. The 2018-19 handbook had mandated that students notify the Dean of Students Office of upcoming protests — but for the first time this year, students must also gain pre-approval for protests with DOSO. Per a Nov. 15 email between University Director of Media Relations Julie Jette and the Justice, in which Jette cited Assistant Dean of Students Alexandra Rossett, students who fail to speak with DOSO would be liable for disciplinary consequences determined on a case-by-case basis. This board finds this restriction problematic ideologically and practically. It both contradicts the University’s social justice-oriented ideology and endangers vulnerable students seeking to make change or have their voices heard. This board calls on the University to revoke or clarify the policy, to remove case-by-case opportunities for subjectivity and bias and to reify their alleged belief in the importance of student action for change.

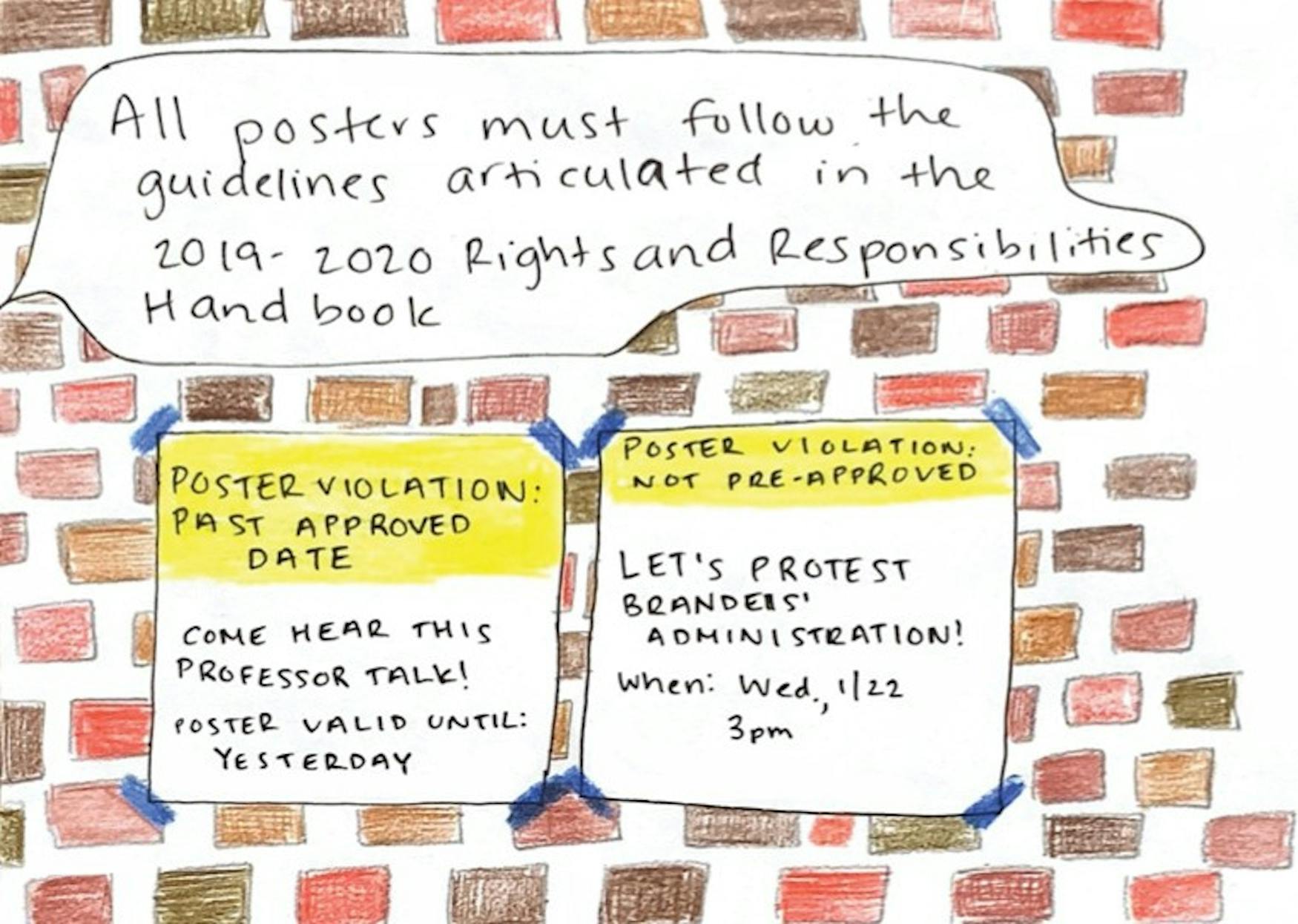

The DOSO website does not contain any mention of student protest policies, nor are they posted anywhere else on the Brandeis website. Without carefully reading the Rights and Responsibilities handbook, students would have little or no indication that DOSO should be involved. For students looking to hold a protest, lack of clearly-posted policies might imply a lack of policies. This oversight should be corrected, so that students can act as fully informed members of the Brandeis community. There are easy solutions for this! DOSO could hold an information campaign as the University did when implementing Workday; they posted signs about the new system, sent numerous emails and held trainings. This provoked students to pay attention and, even if students did not read the emails or attend a training, the majority of the student body was aware a change had been made. Here, there has been little attempt to publicize the new rules.

DOSO should also correct their oversight by creating written forms and policies and linking them on their website. There are many protest guidelines listed in the student handbook; by posting them on the more accessible DOSO website, students will learn about them before breaking them — not afterward. Students could also easily find and fill out the registration forms on the website, and then be contacted by DOSO for a follow-up within a standard timeframe. Should a protest be time-sensitive — if it corresponds to a nationwide event or demonstration, for instance — students could check a box indicating they need the process expedited, and state when they must have approval by. None of these forms should ask about the content of the protest — by restricting that, the University would put itself in the position to police student speech. Rather, each form should solely ask about logistics, location, nonviolence, etc.

The University should clarify and standardize the punishment process as well as the approval one. Right now, there are no rules about what is or is not allowed. Lack of specific and consistent guidelines means that biased punishment could occur. This endangers students who may already be more vulnerable within the school and who have more to fight for: low-income students fighting for new means of dispersing aid, for instance, or another Ford Hall. The University says it values these populations as an essential part of Brandeis, and their voices should be protected. Such groups tend to be punished more severely, may have fewer resources and backup options and face a history of institutional marginalization. It should not be up to administrative or the Student Conduct Board’s whims to decide whose speech merits which consequences. There will always be situations that fall outside of clearly-defined rules, but the administration must remain cognizant of the fact that case-by-case policies grant them discretionary power which can be used to punish different groups of students disproportionately, often exacerbating power imbalances and histories of oppression. The policy worsens this dynamic by increasing administrative discretionary power, rather than reducing it, and it should be reformed to minimize this potential for harm. One way to help alleviate this harm — if the University insists on maintaining prior approval — would be to have a transparent, independent appeals process.

This concern also could be somewhat alleviated by clear policies about what is or is not allowed. These should also be listed as a publically available document. Moreover, speech and content should be out-of-bounds for punishment: the punitive process could focus only on the form of the protest, noting if it was disruptive in areas not allowed or during a certain category of event.

In addition to posting forms and policies online, this board calls on the University to make registration optional. The new University policy was inspired by Princeton University’s, per a Nov. 19 Justice article, but Princeton does not mandate pre-approval in its protest guidelines, section 1.2.3 of their handbook. In response to a Justice query, Michael Hotchkiss, Princeton’s deputy spokesperson, affirmed in a Nov. 14 email that they “encourage, not require, students to register such events in advance.” Moreover, Hotchkiss noted that Princeton’s policies were not “adopted by the University administration,” saying, “They were approved by a vote of … a governing body with representatives from all constituencies on campus.” Brandeis would do well to follow Princeton’s example in these regards. Giving students an equal say in University conduct policies and rendering approval optional would provide students opportunities to connect with administration willingly and to choose whether to seek University support for their movement.

Beyond practical concerns, this board believes the 2019-20 protest policy violates Brandeis’ core — or alleged — ideology. The University’s mission statement claims it is a “center of open inquiry and teaching, cherishing its independence from any doctrine or government.” It goes on to say that it “considers social justice central to its mission” and “honors freedom of expression.” In September 2018, the University adopted a set of Principles and Free Speech and Free Expression. Protest is a form of free expression and is a tactic used by justice movements on campuses, in the U.S. and worldwide. Does Brandeis stand by these stated values, or does this new policy take precedence?

Student protest has also been vital in shaping our school’s legacy. In 1969, a coalition of Black students and allies occupied Brandeis buildings in a movement known as Ford Hall. Their demands — which included adding an African Studies department and recruiting Black students and professors — have shaped Brandeis. In 2015, a student movement calling itself Concerned Students 2015 followed in Ford Hall’s footsteps with demands such as increased diversity and inclusion workshops, increasing the minimum wage for University employees and adding more nonwhite counseling staff. Would anyone argue that these changes have not been beneficial to the University, helping it move in a more equitable direction? Helping it embody its stated social justice ideals? By restricting students’ ability to protest, the University is sending the message that it regrets this legacy.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.