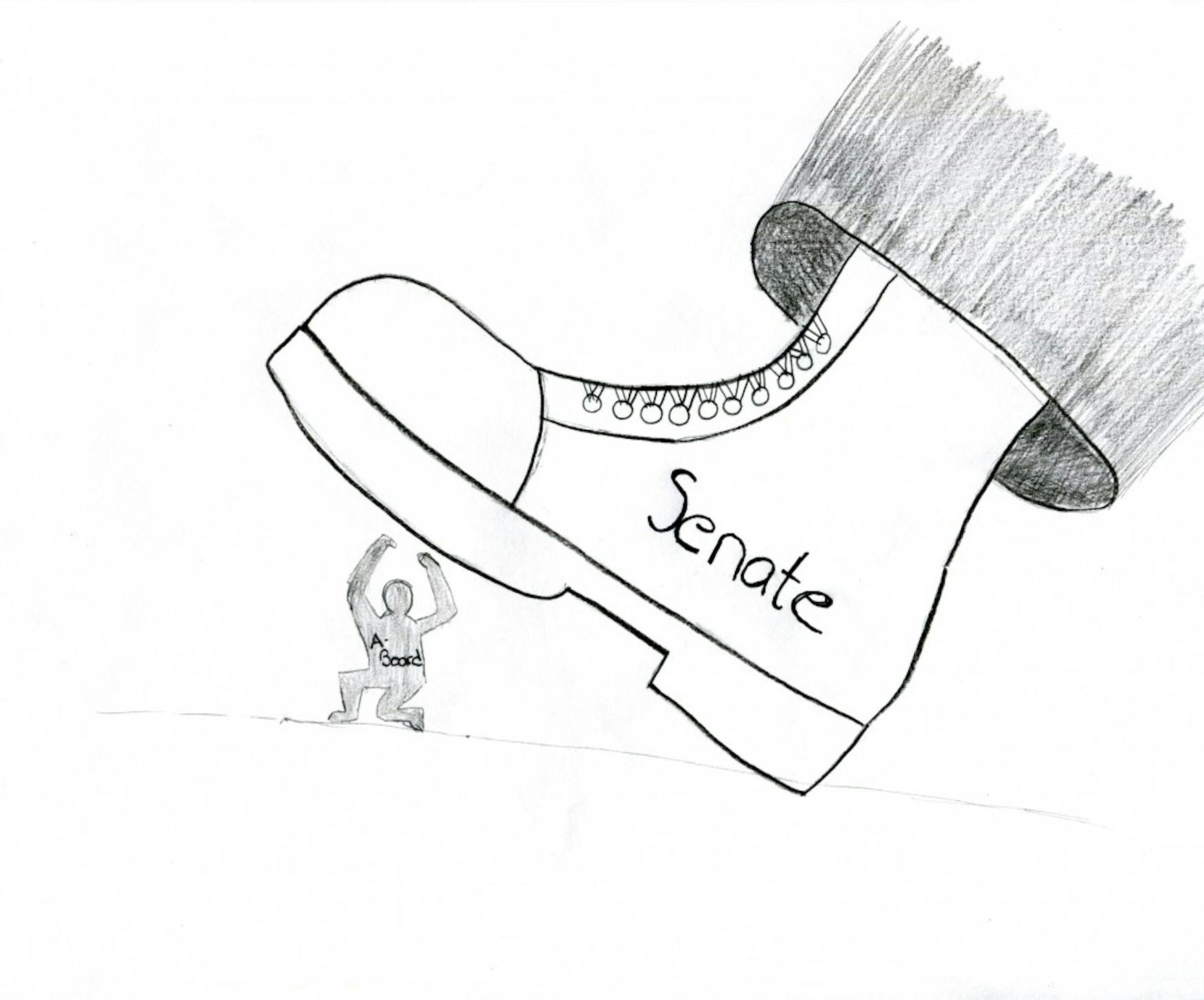

EDITORIAL: Senate should rethink draconian amendments

Class of 2020 Senator Aaron Finkel has drafted two amendments to the Student Union Constitution that would strip the Allocations Board of final authority over all allocation decisions and policies and distribute it between the Senate and Union president. The justification for the amendments states that they would “ensure maximum accountability and fairness,” but this board believes the actual amendments do not effectively address either issue. To properly institute oversight of A-Board without adversely disrupting the balance of power in the Union, both amendments will need to be significantly altered.

Union President Hannah Brown ’19 has the right to veto any A-Board “policy, rule of order, or specific allocation decision” prior to the semester for which the allocation is made, according to Article V, Section 4 of the Union Constitution. This veto can be overturned by a two-thirds vote by A-Board. Finkel’s first amendment — which is co-sponsored by 12 members of the Union, including Brown and Vice President Benedikt Reynolds ’19, but only one member of A-Board — would allow the president to veto these decisions at any time. More concerning is that the amendment also proposes eliminating A-Board’s power to override this veto by a two-thirds majority — transferring that power to the Senate instead.

While the justification for these amendments promises that the president and the Senate would intervene “only if absolutely necessary,” the amendments themselves do not actually restrict when or for what reasons they could exercise this veto power. Finkel told the Justice that the presidential veto is “completely ineffective right now,” because A-Board members “vote unanimously on everything.” But the clear implication of the Union’s constitution is that A-Board, not the president, is designed to have the final say on funding decisions. If the Senate and president dispute the outcome of an allocation decision, they should appeal to the Union Judiciary — not rewrite the Constitution to put A-Board under their jurisdiction.

An earlier draft of this amendment even granted the Senate the power to overturn any A-Board policy or allocation at any time by a two-thirds majority, subject only to the president’s veto. This, of course, would have included allocation decisions involving money requested by the Senate and president. Finkel says that amendments to ensure oversight of A-Board have been considered over the past few years and that these changes were not drafted with recent Union drama in mind. Nonetheless, it’s difficult to imagine that E-Board and the Senate would be so intent on upending allocations policy had A-Board not rejected their $12,000 request for emergency funding several weeks ago.

Allowing the Senate and president to have control over the amount of funding they receive would have presented a glaring conflict of interest; under this new clause, they could easily have vetoed any decision that did not provide them with $50,000 — the Union’s current funding benchmark. While we appreciate that the Senate scrapped this provision, it is difficult to understand how proposing to effectively relegate A-Board to an arm of the Senate and E-Board was ever squared with the stated goal of “fairness.” Finkel told the Justice that the goal of the amendments was to impose “checks and balances” on A-Board, but the appropriate way to do this is to call on a neutral third party such as the Judiciary, not to hamstring A-Board.

Much of the current tension between A-Board, E-Board and the Senate is the result of misunderstandings and miscommunications regarding the way funding is allocated. The Student Union was allocated $45,000 for fiscal year 2018, according to an A-Board email obtained by the Justice. Of that $45,000, over $15,000 remained at the end of the fiscal year. Based on those Union expenditures, or lack thereof, A-Board set the Union’s fiscal year 2019 budget at $38,000. Finkel explained that E-board and the Senate requested the emergency funding to “assure everyone in the Union that [they] have enough money,” because Senate projects were stalling due to a perceived lack of funds to implement them. But their emergency request did not mention that — nor did it specify how much money these projects would require, or clarify that the remaining money in the Senate’s discretionary fund had largely been set aside for the fall and spring Midnight Buffets. Instead of providing these details, they asked A-Board to reach out if they needed additional information — which A-Board would have been wise to do, though they were not strictly obligated to.

A-Board denied the emergency request and later overturned Brown’s veto of that denial, arguing the Union hadn’t demonstrated an urgent need for funding or specified what it would be used for. Brown wrote that the denial of funding “limits the ability of the Student Union to provide meaningful and frequently difficult to anticipate services to the student body, ... interact with students through co-sponsorships and innovative projects, …. [and] serve as efficient representatives for students.” In their email to overturn Brown’s veto, A-Board wrote that they will provide funds on a “project by project basis once the Union's finances actually represent the need for additional funds.”

A-Board and E-Board are both correct. A-Board cannot allocate money without receiving specific details about what it will be used for — this is true even of the Union and other secured clubs. And the Union cannot function effectively without a way to swiftly access funds for previously unanticipated projects. The solution here is better communication; introducing polarizing constitutional amendments will only make matters worse.

The second amendment, the A-Board Operations Reformation Act, is sponsored by the same Union members and two other senators. Article V, Section 2 of the Union Constitution establishes that A-Board can pass “policies and rules of order” by a majority vote. Finkel’s amendment would have the Senate, not A-Board, approve any policies by a majority vote. The amendment’s justification does not name any current A-Board policies or rules that Finkel or the co-signers believe are problematic, nor does it explain why the Senate specifically is better qualified to have the final say on the workings of A-Board.

Finkel expressed his frustration that A-Board could change funding policies without the input of the Senate, which he says frequently receives complaints from students about the allocations process. A better solution would simply be to require A-Board to provide more detailed explanations for any changes they make, and to direct the Judiciary to examine these policies if any issues arise. In the current climate of distrust between branches of the Union, granting the Senate power to veto A-Board policies, without clearly expressing what immediate problems this would solve, only invites further tension and potential gridlock.

Finally, there is already a significant checks-and-balances mechanism in place: voting. Students have the power to vote any Union member out of office. If they are dissatisfied with A-Board’s conduct, they can appeal allocations decisions, vote for new A-Board representatives or run themselves.

This board hopes that E-Board and the Senate will rethink their approach to modifying the allocations process. Any changes they implement should advance their intention of ensuring fair oversight, not simply fracture already-strained relationships by overturning the Union’s distribution of power. As major bodies of student government, A-Board, E-Board and the Senate should focus more on cooperating to improve student life.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.