Labor economist explores the role of gender in the conflict between career and family

“The quest for career and family has been a long journey, so we are not yet at the end of the road,” Claudia Goldin said as she opened her talk on the social and economic struggle of choosing between pursuing careers and families. Her talk took place last Thursday and was entitled, "A Long Road: The Quest for Career and Family," and discussed how American society has developed through trends in labor economics.

Goldin, the Henry Lee professor of economics at Harvard University, is a labor economist “best known for her historical work on women in the U.S. economy and the gender wage gap,” according to the event description. Goldin explained that, starting in the 1970s, college-educated women began defining their success as having both a career and a family. By the 2000s, college-educated women had entered high-paying, male-dominated fields in large numbers.

Goldin presented a graph that showed how birth year corresponded to the percentage of women who had not given birth by a particular age. The number of college-educated women without children has dropped substantially in recent years, something that is “pretty astounding,” according to Goldin. “When I was an assistant professor, and for many years after, women assistant professors were not pregnant, [but] now they are,” she said.

Meanwhile, she said the presence of gender inequality still means that women in relationships devote more time on average to families than their male partners.

Goldin turned to her own term, “temporal flexibility,” to explain why women in couples end up being paid less than their husbands. She explained that this term comes from the difficulty of controlling how each partner uses their time while still maximizing household income.

According to Goldin, the distribution of labor between a couple changes over time as a result of many factors, including marriage, children and moving residences. Thus, the gender gap is actually measured by a set of numbers, not just one.

Goldin first highlighted the problem of labor market bias as contributing to this inequality. “The real problem is that many jobs, especially the higher-earning ones, pay far more on an hourly basis when work is on-call, longer rush, evening, weekend and by-and-large unpredictable,” she said, pointing out that “these time commitments interfere with … family responsibilities.” As women traditionally take on these familial responsibilities, this means that women cannot take on this higher-paying work, she said.

Goldin gave a generalized example of a highly educated couple, with the wife being “professional, highly respected, on-call, at home,” and the husband being “professional, highly respected, on-call at the office.” She explained that “he earns more than she does, even if they work the same number of hours.”

Goldin explained that these two job situations can be seen as “flexible,” in which the person can work from home and also attend to household tasks, and “inflexible,” in which the person cannot work from home but is paid more for their inconvenient work hours. If a couple both took inflexible jobs, they would get extra income, but they would not have time to get household tasks done — especially the important task of child care. If both took flexible jobs, they would lose out on extra income. This means that a couple normally has one person take a flexible job — and do household work — and one take an inflexible job, creating gender inequality even if both work the same hours.

“It is the condition of those periods and hours offered by most jobs rather than women’s own competitiveness that results in such problems,” Goldin said of this inequality. She noted that although “wages are seen soaring in the post-1980 period, the inequality is also seen soaring.” She summed up the issue by saying, “The problem is how work is structured.”

Goldin then turned to look at the 20th century historical trends of women college graduates facing this career-family dichotomy.

Goldin divided the 20th century’s women college graduates into five cohorts, based on the year they graduated. The cohorts were divided into 1900-1919, 1920-1945, 1946-1965, 1966-1979 and post-1980. Goldin then looked at the choices each cohort made: The first cohort chose a family or a career, the second cohort chose a job and then a family, the third cohort chose a family and then a job, the fourth cohort chose a career and then a family, and the fifth cohort has chosen career and family.

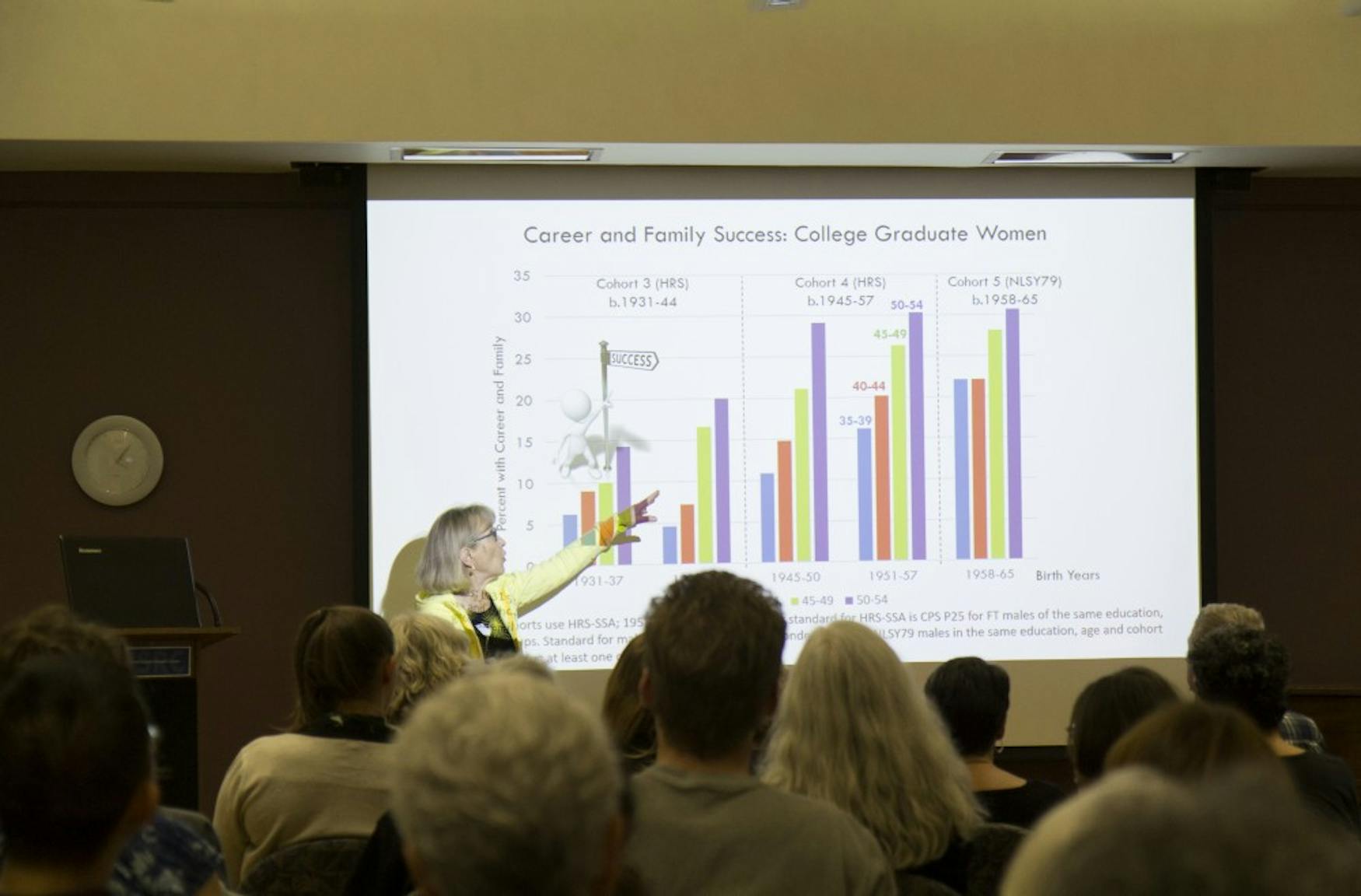

Looking at the third, fourth and fifth cohorts, Goldin said that “there has been considerable improvement.” Yet some imperfections still exist, as Goldin pointed out that “the rates [of having both a career and a family] are still low for young women … much lower than those college-graduate men.” She explained that 50-60% of college-educated men have families and careers, while only 20-30% of college-educated women have the same.

For Goldin, the center of this gender inequality stems from the high price women pay in lost wages for choosing jobs with flexible hours. “Any solution must be about lowering the cost of what I am calling temporal flexibility, the ability to control these hours,” she said. She jokingly suggested that “the simplest way of doing that is to create perfect substitutes” for people, like clones. She did suggest that “really good IT” could help to play this role of a substitute. A more realistic solution that Goldin suggested was firms lowering all of their costs of production, which could help decrease the cost of temporal flexibility.

After her talk, Goldin took questions about labor economics from the audience.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.