DeisRobotics shares past triumphs and plans for this coming semester

In an interview with The Justice, the Club’s leadership talks about hands-on plans for battle bots, workshop offerings and open door hours for newcomers.

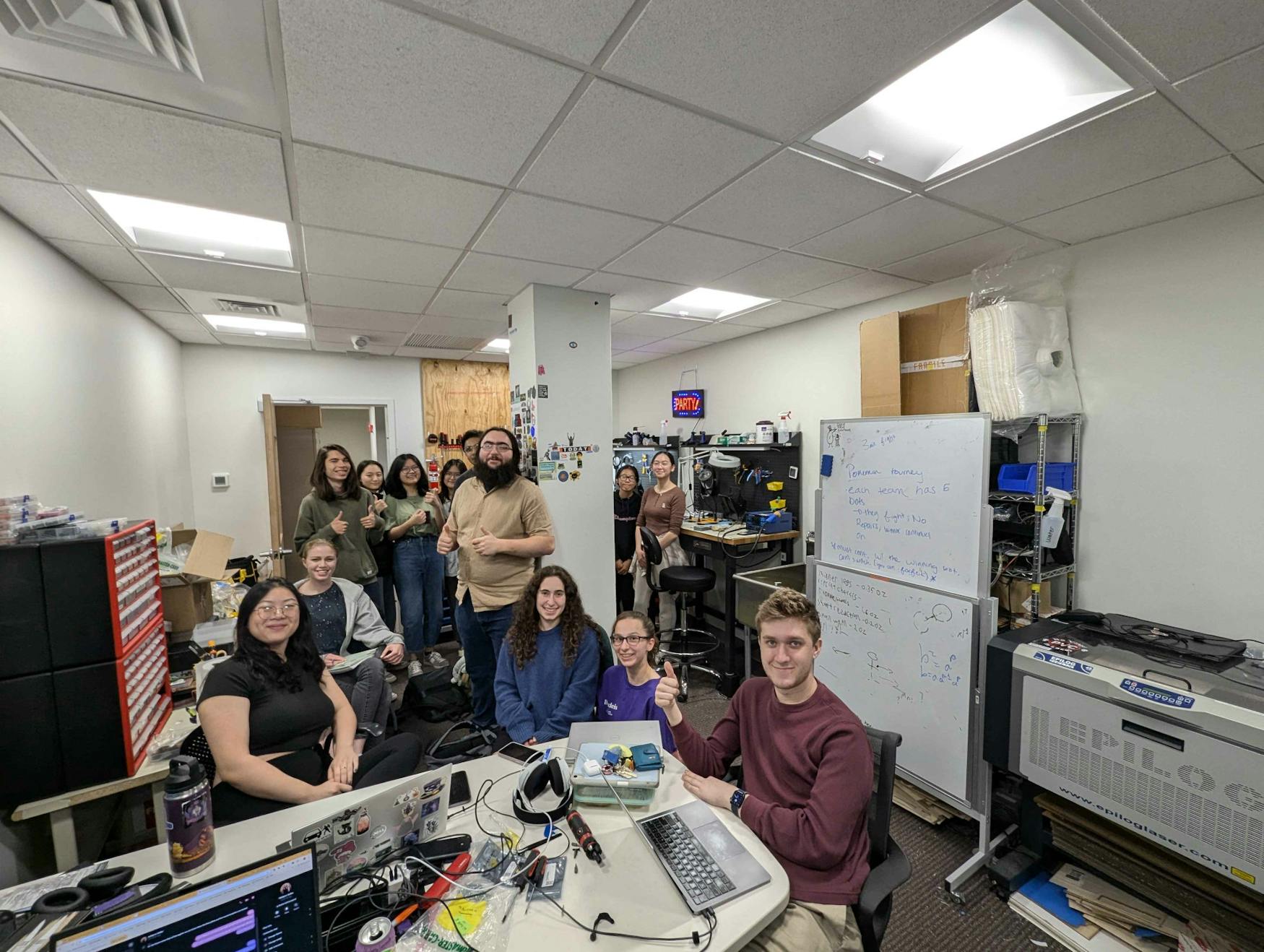

Tucked away in the back of Goldfarb Library is the Automation Lab — home to DeisRobotics, Brandeis’ very own robotics club, which competes regularly in National Havoc League tournaments in Norwalk, Connecticut and holds informative workshops for students interested in engineering and associated skills. Last semester, the team qualified for the NHRL world tournament and won second place in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Combat Robot Competition.

“Our [university] is kind of notable in this space, and I feel like a lot of students don’t know that,” Daphne Yan ’26, a co-president of the Robotics Club told The Justice in a Sept. 25 interview.

In the same interview, Samuel Herman ’27, the club’s other co-president, agreed with Yan’s sentiment, stressing that Brandeis’ reputation as a liberal arts institution should not insinuate that its engineering capabilities are lacking. Instead, the University’s flexibility for interdisciplinary studies is an added advantage. He highlighted that the robotics club holds workshops to make the club as accessible as possible to students across academic fields. In fact, many members of the robotics club are not involved in science, engineering, technology or math studies.

While the Robotics Club encourages its members to pursue projects beyond BattleBots, these competitions are one of the organization’s primary focuses. Yan explained that for each NHRL tournament, some members of the club prepare their own robot to participate in the rounds of combat, and that Brandeis mostly participates in one pound and three pound competitions, the difference being in the weight of the robots fighting.

Herman explained that each match is about three minutes long, and the overall goal is to “disable the other robot, either by ripping it apart [or] hitting some pieces of electronics that make it stop working.”

Even though these robots are small and light, they are very powerful. Herman explained that they have the strength of “a small rifle” through the use of lithium ion batteries, which are designed to have high energy density. “Those are then connected to a set of electronics that drive brushless motors,” he shared. These motors are the same ones used in model airplanes or drones. Herman explained that these motors then spin hardened steel disks, which generates the energy needed to power the robot.

“Note that just basic physics, the heavier the weapon is, the faster — or the more torque — you can get pushed into it. The more damage it’s going to do,” added Leo Gray `27, the club’s vice president.

Herman clarified the power behind the weapon isn’t the only factor that determines its capability for damage. “There’s a lot of design constraints that go into figuring out how to unload that power onto another robot,” he said.

The team mentioned the power behind these robots can often cause dynamic exchanges during competitions, despite their small size. Yan recalled that there have been fights where robots get ripped in half, rounds where fires have started and sparks have flown.

“Regularly, bots hit the ceiling and break the lights on top of the cage,” added Tim Hebert, the head of the Automation Lab and the robotics club’s staff advisor.

In past competitions, Gray has seen weapons such as a jaw similar to a bear trap that could latch onto robots, and a flamethrower that could melt robots. The flamethrower was at such a high heat concentration that it melted the cage’s plastic.

Gray shared that the tournament periodically adds different regulations to its rule sets — such as a 50% weight bonus if the robot does not require wheels in order to move. “So right now, I’m making what is called a torque walker, where the bot basically has weapons mounted at an angle, that way, when it spins up, it can sort of shift its body around using the torque,” he described.

Hebert stressed that the most celebrated aspect of combat robotics is “doing things that are unique and creative.” Some of his past creations could be controlled by a drum kit, “Dance Dance Revolution” dance pad or “Guitar Hero” guitar. “A bad idea, executed well … is celebrated within the community.” Hebert fondly recalled winning his round of combat with the robot using the dance pad. He believes that part of why robotics is so successful at the University is because so many members of the club come from varying disciplines. “Folks coming from a different background and then getting their hands on some of these tools — they have more of that creative aspect, and they can approach the problem in a different way,” Hebert explained. He said that the most learning takes place when a robot loses, because it allows its creator to troubleshoot what went wrong.

“So as long as you go in with the right mentality of like, every single fight is a learning opportunity, it doesn’t actually matter if you win or lose,” Hebert said. “It matters if you learn something, because then you’re making progress.”

Having a culture of trial and error also helps to keep the environment lighthearted and collaborative, Yan shared. However, it also requires a robust set of safety regulations, she stressed. “The more you learn about [lithium powered] batteries, the more you realize, they’re just tiny bombs,” she said, emphasizing that all robot testing and driving has to take place within caged test runs. The club has someone keeping time of the battery usage because overuse can damage the batteries. Meanwhile, another person must hold a sand bucket in case there is a battery burst.

“That’s never happened, and it’s not going to happen,” Hebert said. He explained the club’s intricate contingency plans. Additionally, the NHRL has safety regulations for robots’ weapons — each one has to have a lock in the form of a solid metal bar, running across the machine, for instance.

The club expressed their love for the sport on numerous occasions. They are ever optimistic about the future of their bots and are not afraid of the carnage. “We don’t care if it’s the other robot or our robot … it’s fine to get destroyed,” said Herman. He explained that members of the club can always go back to the design stage and consider ways to improve each iteration of their robot.

Looking forward, DeisRobotics hopes to host more events. They have a full sized testing cage to become a local “hub” for BattleBot competitions here at the University, according to Herman. He added that the club is also looking to start creating robots to fight in higher weight classes, such as 12 and 30 pounds, and with this larger cage, they could test these heavier robots right on campus.

In the meantime, DeisRobotics will continue to hold workshops in topics such as 3D printing, soldering and more. Herman emphasized that the club hopes to leave its members with lifelong engineering skills that can come in handy across disciplines.

— Editors Note: Justice Senior Editor Eliza Bier ‘26 is a student worker manager at Brandeis Design and Innovation and did not edit or contribute to this article.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.