Reevaluate minimum wage to prevent homelessness

Today, over 610,000 U.S. citizens are living without a roof over their head, according to a 2012 report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Three million more suffer from homelessness at least a few nights a year. Even more telling than these staggering statistics is the idea that the American dream is clouded by such suffering: one homeless person can remind us of the egregious wealth gap that persists in America. Narrowing this socioeconomic gap will require a large effort by the national government, one that must make homelessness prevention a priority, not an option.

Recent trends charted by the National Alliance to End Homelessness show that the number of homeless individuals is increasing in certain states despite a decrease in homelessness nationwide. Furthermore, the problem is becoming more perverse as many Americans rise into the upper echelons of society, separating themselves from the impoverished. Nowhere is this more apparent than in San Francisco, where entrepreneurs who work for multimillion-dollar companies walk on sidewalks littered with dog and human excrement alike. The irony here highlights a shameful truth: in America, some people live like dogs and others like kings, and this is unacceptable. In delving into capitalism and political jamboree, America has left some of our own out on the street without two dimes to rub together.

To put this chronic problem into perspective, one only has to look so far as Hurricane Katrina and other natural disasters. During the hurricane season of 2005, the city of New Orleans was flooded with ten feet of seawater. People were stranded on their roofs for days with limited access to food, water and other necessary resources.

Delayed response by the New Orleans mayor and the Bush Administration sparked national outrage as images of survivors streamed through the media. This strong reaction shed light on the plight of living without a home. What was not translated was that the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina—being stranded—is a reality the homeless face every day.

Some may argue that homelessness is self-inflicted, whereas the victims of Hurricane Katrina were innocent in their misfortunes. However, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development reports that one-third of homeless people have severe mental disabilities. Others suffer from domestic violence, family disputes and depression.

If such skeptics still insist that the two cases are different, they have a serious misunderstanding of mental health. The bottom line is that in addressing human suffering, one cannot be biased.

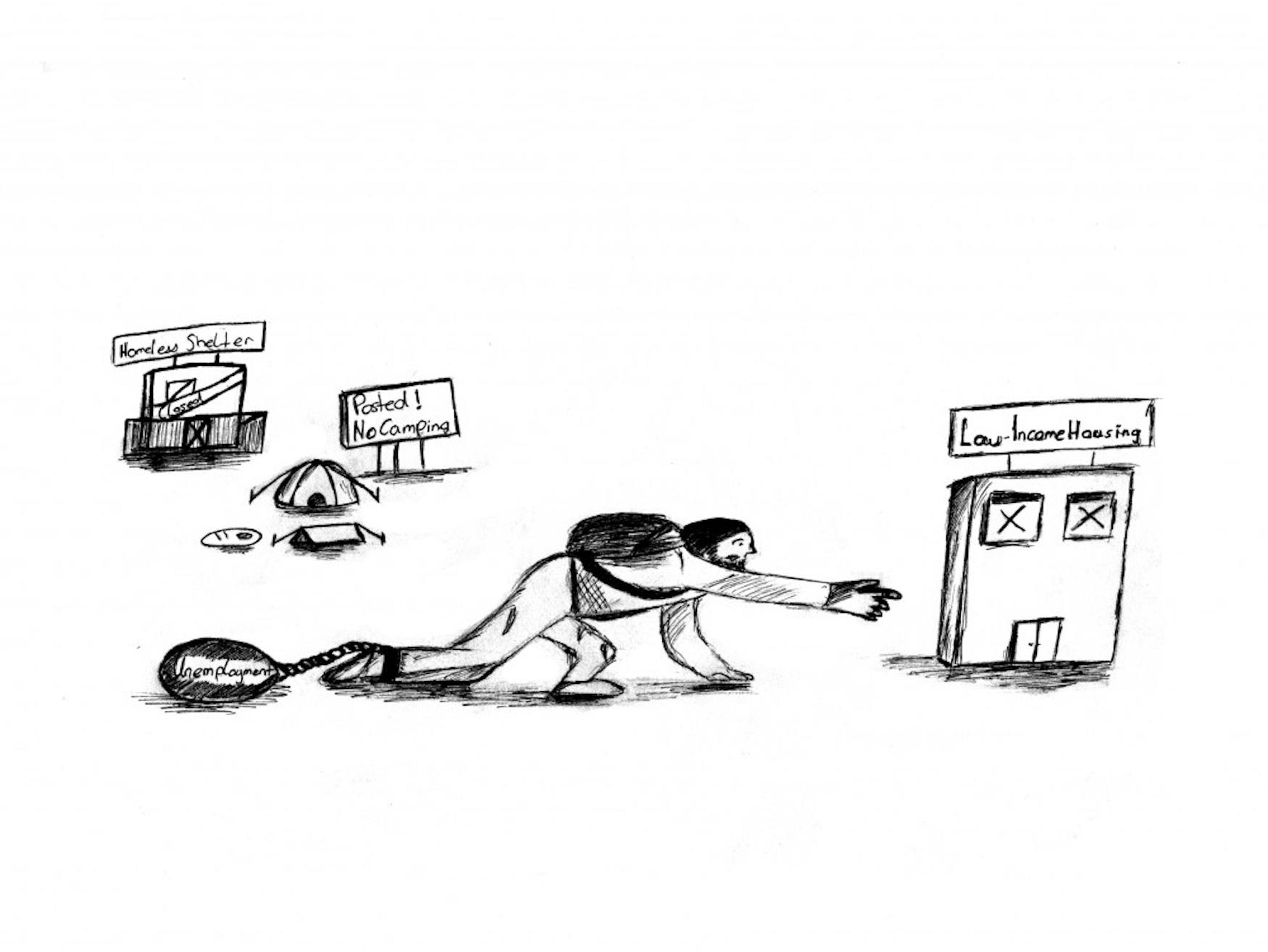

Unfortunately, the local government’s response has been guided by the idea that homelessness is self-inflicted and blameworthy. In fact, many cities are even making homelessness a crime. According to the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, “In Orlando, Florida, 34% of homeless people are without shelter beds, yet the city restricts or prohibits camping, sleeping, begging and food sharing.” Similar laws can be found in 187 cities nationwide, a trend that is growing as more and more people congregate in search of jobs. Many of these cities, including Orlando, have large wealth gaps, making the contradiction flagrant.

Our laws define who the homeless are, while simultaneously making their existence illegal. Such cities’ obsession with shielding the wealthy from the poor has had dire effects.

Many volunteer organizations have been shut down, and individuals have been fined just for giving food to the homeless. Rather than break the cycle of homelessness—which is already plagued with adversity—many of our states are perpetuating the problem by criminalizing it.

Even more unsatisfactory is the nation’s response to homelessness. What social programs are federally funded, such as food banks and shelters, are insufficient to meet high demand—for some, this means bearing insufferable cold and hunger for the night. According to a 2014 Wall Street Journal report, limited shelter availability in cold areas like North Dakota and Boston have led shelters to rent motel rooms for the homeless or simply turn them away. Despite good intentions, the reactionary approach to solving homelessness is bound to fail anyway. Funding social services which assist the homeless rather than targeting those in extreme poverty will never stop people from becoming homeless in the first place.

The Obama administration recognized this process and attempted to respond to the crux of the issue. A provision of the 2009 HEARTH act allowed state bankruptcy judges to modify mortgages in an effort to help people keep their homes. Foreclosures were at an all-time high during this period, leading to mass unemployment and a stagnant economy. However, the provision was defeated in the Senate later that year, and the local economies, no doubt, continued to plummet.

Other policies aimed at making low-rent housing available have failed as well. As a result, low-rent housing has been eliminated in lieu of a recovering economy.

According to a 2012 study conducted by the National Low Income Housing Commission, “In 86% of counties studied nationwide, the housing wage (the estimated full-time hourly wage a household must earn to afford a decent rental unit) exceeds the average hourly wage earned by renters.”

The homeless seem to be stuck between a rock and a hard place. Living on the streets involves camping places and receiving food—which is now being made illegal—yet rent is still unaffordable with a minimum wage job. This response is reversing the work of hundreds of organizations by making homelessness extremely difficult to overcome. It is cast with chains.

A more comprehensive solution is needed if the burden of homelessness is to be alleviated. First and foremost, the government needs to change its approach. Rather than have law enforcement take punitive measures against the homeless, social services should be expanded to rehabilitate those without a home and situate people living in extreme poverty. Moreover, minimum wage should be increased nationwide so that Americans can afford low-rent housing.

The problem must also be addressed locally. Businesses need to open their doors to the homeless when the weather is bad. Individuals need to pressure Congress to decriminalize offering food to the homeless.

And people need to dedicate time to volunteering at organizations that assist the homeless. Many of these organizations are understaffed, a sign of Americans’ apathy toward the issue of homelessness.

The homeless have been rejected by their families, the law, the economy and society. Rather than waiting for such superstructures to fix themselves, people need to reach out to the homeless, if not because of their own excessive wealth then out of the desire to be a decent human being. Access to basic shelter is necessary, because the homeless are just as human as everyone else. And any human will wonder what will the Statue of Liberty symbolizes in an America that lets its citizens slip through the cracks.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.