Philosopher’s work remembered

Last week, the Brandeis community gathered for a two-day conference to explore the critical theory of philosopher Herbert Marcuse to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the publication of his 1964 book, One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society.

The conference spanned from Wednesday to Thursday, with each day featuring a keynote address and several lectures and panels in Rapaporte Treasure Hall in the Goldfarb Library.

Marcuse was a member of Brandeis’ faculty when One-Dimensional Man was published. From 1954 to 1965, he taught courses in the History of Ideas program and in the Politics and Philosophy departments at the University.

Prof. Martin Jay, the Sidney Hellman Ehrman Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, gave the first keynote address on Wednesday evening, titled “Irony and Dialectics: One-Dimensional Man at 50.” He first spoke about Marcuse’s views, describing the philosopher as an “irrationalist of capitalist society as a whole,” meaning he saw capitalism as a type of absurdity. Yet Jay explained that Marcuse’s critics said that Marcuse did not fully understand capitalism. Jay moved on to discuss One-Dimensional Man in the context of the mid-1960s. He mentioned that the One-Dimensional Society was largely responsible for the “social revolts” in the 1960s. This One-Dimensional Society, according to Marcuse, was a society in which mass media and culture prohibited many ideas and thoughts.

Jay also explained that, according to Marcuse, individuals are responsible for their own fate. While some may believe that Marcuse and Sigmund Freud’s ideas are similar, Jay said that in contrast, Marcuse has “some hope for historical change,” or a hope that the future can change despite its history. Conversely, Freud’s theories are much more static. Jay did not think there was progress regarding Freud’s theories on psychoanalysis because Freud felt that his theories were merely in regard to a permanent human nature. Jay noted that Marcuse is more of a spin on Freud because Marcuse sought to better society from its social wrongs, while Freud could not foresee changes in society.

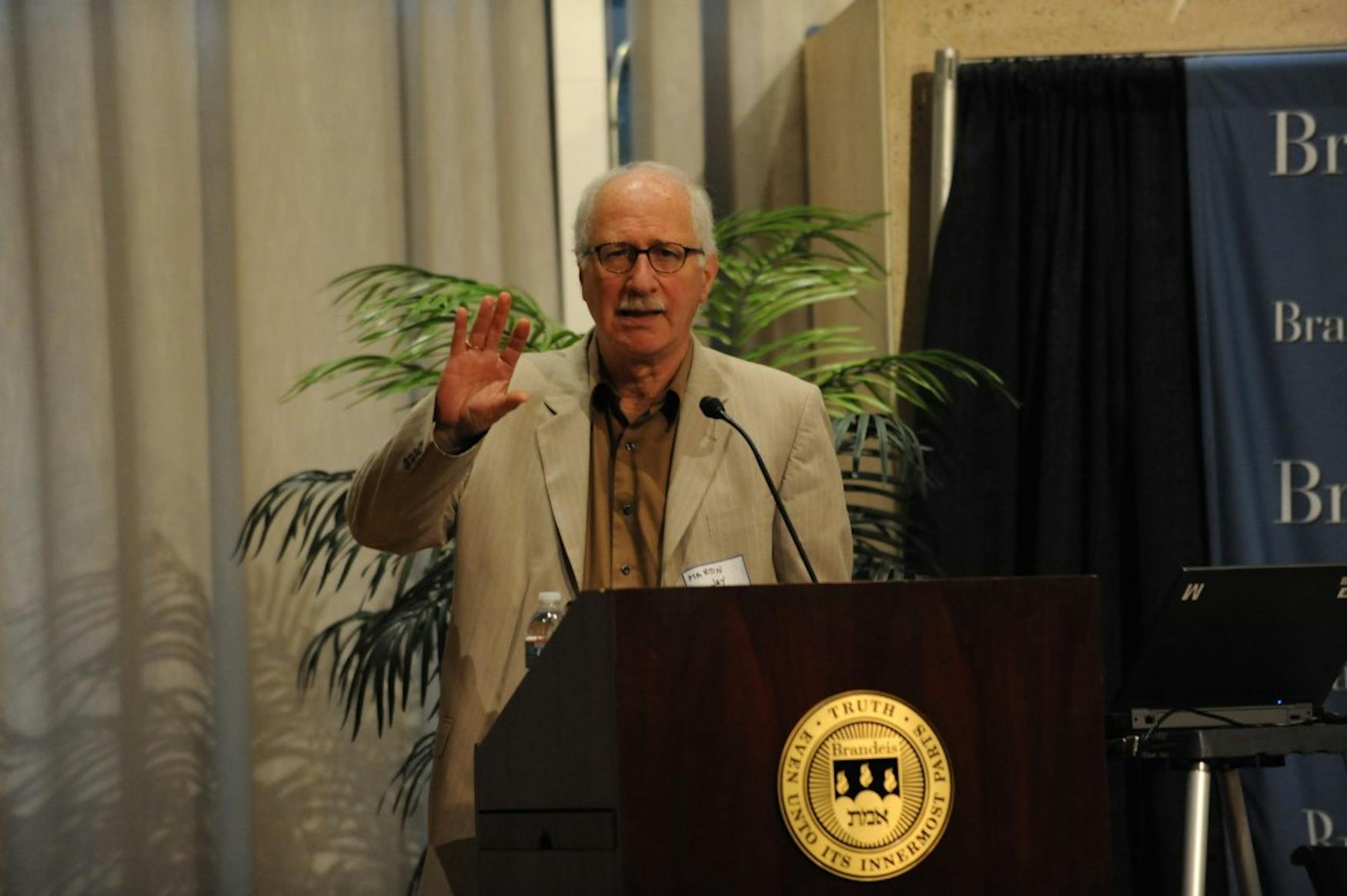

On Thursday afternoon, Douglas Kellner, the George F. Neller Philosophy chair at the University of California, Los Angeles and leading Marcuse scholar, delivered the second keynote address. Prof. Patrick Gamsby (HOID) introduced Kellner.

Kellner spoke to the audience, saying that, “In all my years as a Marcuse scholar, it is great to be, for the first time, at Brandeis.” He authored the book One-Dimensional Man: Relevance Across the Decades from 1964 to 2014 and spoke for just under half an hour about Marcuse’s work and his own scholarship before opening the floor for questions from the audience.

He addressed differences between the earliest manuscript of One-Dimensional Man and its later publicized form. “If you look at the published edition—in 1964—you see its critical theory of society that emerges as framework,” noting that from the manuscript to the published edition, “the text shifts in focus from aesthetics to politics,” he said.

“Marcuse is at once the most pessimistic thinker you can imagine but also the most optimistic,” Kellner explained. He also touched on Marcuse’s connections to and analysis of Marxism, saying that Marcuse was one of the first male Marxists to support both feminism and the civil rights movement when it was not common or generally accepted to do so.

Kellner continued speaking about Marcuse’s evolving assessments of Marxism, communism and fascism in One-Dimensional Man. “It’s really unfair to call him just a communist or a Marxist,” Kellner said. “Marcuse was one of the few people who really stood up to the Cold War.”

In attendance at the conference were several members of Marcuse’s family, including his son. The conference was sponsored by the departments and programs of American Studies, English, European Cultural Studies, German, Russian and Asian Languages and Literatures, the History of Ideas, Philosophy, Politics and Sociology; the Center for German and European Studies; the German Academic Exchange Service; the Louis D. Brandeis Legacy Fund for Social Justice; the Mandel Center for the Humanities; the Office for the President and the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.