The Failure of ‘Euphoria’ and ‘Assasination Nation’

To understand “Euphoria”’s season 2 character failings, you have to see “Assassination Nation,” and how Sam Levinson keeps screwing over his heroines.

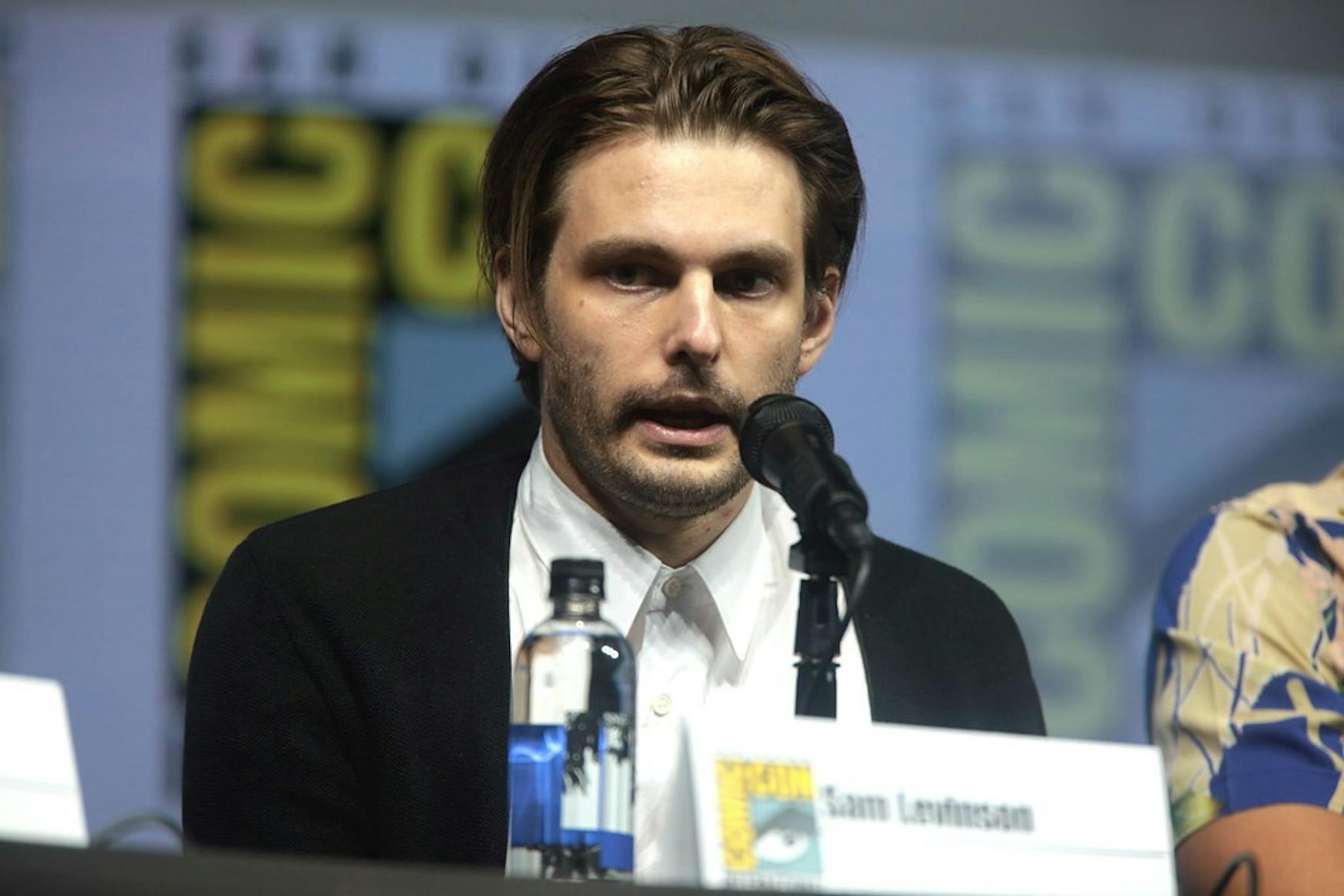

Recently, the New York Times published a piece about how Sam Levinson, the director of HBO’s smash-hit show “Euphoria,” had been disavowed by the show’s own fanbase. Reports had come out that a few actresses on “Euphoria”’’s set were put in positions where they had to advocate not to be nude. This, coupled with a series of messier, unsatisfying plotlines for a few beloved characters, led to a change of pace in the conversation around Levinson’s creative direction.

It’s a twist not unlike author J.K. Rowling’s fall from grace after the Harry Potter fandom abandoned her following transphobic comments that she made in 2020. Indeed, “Euphoria” and its ensemble of traumatized characters appears to remain beloved by fans, just as The Boy Who Lived lives on.

But regardless of the separation fans have made between Levinson and “Euphoria,” it’s impossible to completely sever the two from each other, mainly because the show’s deadpan narrator, Rue – Zendaya – is based on a younger version of himself. This is part of what makes her character so multidimensional and well done: it’s driven by autobiography. But it’s also here that things get tricky for Levinson, especially when it comes to the ways in which the women around Rue are portrayed. How might we address the triumphs of season two while also acknowledging the ways in which it fails its other protagonists?

For example, Rue’s friend Kat – played by Barbie Ferreria – seemed to be almost written out of the show entirely, aside from a few half-hearted one-liners and some random sexy dancing. Other characters – Rue’s sister Gia who was played by Storm Reid – and protagonist Jules – portrayed by Hunter Schafer – showed no character development at all. Worst of all, Cassie – Sydney Sweeny – morphed into a one-dimensional mess of a villain who destroys her relationship with her best friend, her sister, and her own autonomy all for the love of the show’s biggest antagonist, Nate Jacobs – played by Jacob Elordi. Unlike Cassie’s portrayal in season 1, which left her with a newfound independence and sense of empowerment, her endless nude scenes seem to be written to purposely leave her without a backbone.

But there’s a blueprint to these character failings. From allegations of voyeurism to empty monologues, “Assassination Nation” did it first.

Written and directed by Levinson and released in 2018, “Assassination Nation” follows a group of teenage girls in Trump’s America as their town, Salem, descends into chaos following a data leak. Like “Euphoria,” “Assassination Nation” tackles topics like transphobia, toxic masculinity, relationship abuse, and sexual assult through having its four female protagonists survive a stylized gauntlet – or, per the town’s name, a witch hunt – of violence from the men around them over the course of a single night. It’s full of vehement monologues about the patriarchy, delivered by cynical narrator Lily – played by Odessa Young.

It’s supposed to be femminist, but the film delights in showing its heroines cornered: a knife pushed into Lily’s mouth, held by her assaulter, or a noose being tightened around Lily’s friend Bex – portrayed by Hari Nef – in an attempted hate crime. For all of Lily’s devastating monologues on girlhood and autonomy, the movie seems incredibly contingent on voyeurism. This wasn’t something missed by critics. “The filmmakers have the gall to spend nearly two hours assaulting the audience with sexualized violence, only to turn around and offer up a patronizing lecture on the contradictory social conditioning of women as some kind of grrrl power rallying cry,” wrote Katie Walsh on “Nation” for the Los Angeles Times. For the same reasons, audiences rated “Assassination Nation” a 55/100 on Rotten Tomatoes.

For Levinson, the takeaways from “Assassination Nation”’s critical reviews should have instigated a push to do better by his female protagonists. And it did, for the most part, in the first season of “Euphoria.” But in season two, his heroines become boxed in by their own storylines, just as “Assassination Nation”’s were. Fight they can, but catch a break they cannot. Between “Assassination Nation” and the second season of “Euphoria,” we’re supposed to accept when Levinson’s female protagonists implode into one-dimensional shells of their former selves, simply because we’re shown how they were traumatized into it.

“You can control what I eat, what I wear,” says Cassie to Nate in a stomach-churning, pastel-lit monologue. Levinson wants us to accept the monologue as reasonable, because we saw everything that brought Cassie to the point of delivering it. And boom, that’s where the season leaves her.

If Levinson wants to keep developing his characters, he’s going to have to move past aestheticizing the hell his female protagonists go through and start focusing on how to let them keep their autonomy and multidimensionality in the face of it. There’s a line between realistic depictions of trauma and trauma porn that Levinson has failed to acknowledge, and it’s biting him in the butt. It’s not clear if Levinson can uncancel himself before the third season of “Euphoria,” but getting a writers’ room couldn’t hurt.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.