Contamination without communication? University leaves students and staff out of the loop about high lead levels and water fountain closures

The Justice spent multiple months investigating reports of lead contamination in drinking water on campus and speaking to concerned students and faculty, as well as Manager of Environmental Health and Safety, Andrew Finn.

On Sept. 22, 2021, chemistry and biochemistry students and professors received an email with the subject line “IMPORTANT! Do NOT consume water from the faucets in Edison-Lecks” from Meghan Hennelly, a Chemistry department administrator and manager of space and buildings for the division of Science at the University. Sent via a listserv titled “chemall-group,” those on the email blast were some of the first students to receive official word about lead levels in various buildings around campus.

Attached to Hennelly’s correspondence was a notice from Brandeis’ Facilities Services Director Lori Kabel. Kabel said that Facilities Services had been working with Environmental Health and Safety to perform random sampling on water from water fountains in various buildings across campus. She explained that water testing is performed periodically throughout the year, but was performed at an increased rate over the summer and early fall due to COVID-19 and the return of employees to campus. She stated, “Unfortunately, the results in Brown [Social Science Center] and Edison-Lecks [Science Building] read higher than the Environmental Protection Agency guidelines for lead. For this reason, we will be turning off all of the water fountains in both Brown and Edison-Lecks until we can come up with the cause and solution to rectify this issue.”

On Dec. 16, in response to the Justice’s interview request and list of questions originally directed towards Facilities, Andrew Finn, manager of EHS, provided a statement on Kabel’s behalf. “As we transitioned back to on-campus activities, the [University] administration, operations, and Environmental Health and Safety had concerns about drinking water having been sitting with little or no flow for an extended period of time,” Finn said, and explained, “Buildings [were] identified as possibly being at risk due to the age of the plumbing materials … and [we] proceeded with three rounds of testing.” He did not provide information requested by the Justice about the dates that this testing occurred, a list of buildings that had been tested, or the results of this testing.

Finn explained the federal standards used to identify lead-contaminated water: “The testing did identify lead levels in water samples from water bubblers which exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency ‘action level’ of 15 micrograms/liter (parts per billion).” The “action level” is the threshold for acceptable lead levels in drinking water, “which indicates to the water supplier that there is a need for corrective and preventive actions to identify the source(s) of lead and reduce exposures,” Finn wrote.

Testing begins

It appears that testing began as early as June, when students were largely off campus for the summer recess. A student who worked in the psychology labs of Brown over the summer explained to the Justice that they had received a notice in June instructing people working in the building not to drink the water. They added that there were signs put up in Brown’s bathrooms saying the same and that a water dispenser was implemented.

However, Prof. Sarah Lamb (ANTH) explained to the Justice on Feb. 7 that during the first weeks of the fall semester, there were neither signs at the fountains nor a dispenser in the building. Lamb continued, “Early in the fall semester, there were signs put up saying ‘water is unsafe’ at the fountains and in the bathrooms … but no other water source was given to us for some time. We had to bring water from home or go thirsty.”

Since then, Lamb added, a dispenser was installed, but that “The first period in the fall when we had no drinking water in the building was tough, and added to the general sense of pandemic strangeness and disarray.”

Follow-up testing

On Oct. 22, Hennelly forwarded an email she had received from Finn that same day to the “chemall-group” listserv. Finn’s email was sent to building operations administrators for the Psychology, Anthropology, Physics, Mathematics, Judaic Studies, and Library departments, along with Hennelly. In this email, Finn detailed an additional round of water testing EHS had done on various water sources in buildings across campus on Oct. 1 and Oct. 5 — including water sources in Edison-Lecks and Brown other than the fountains that had been confirmed to have tested positive for increased lead levels in the months prior. These buildings also included the Lown Center for Judaic Studies, the Goldfarb-Farber Library, Abelson-Bass-Yalem (which houses the department of physics), and Goldsmith (which houses the department of mathematics).

Finn’s Oct. 22 email to building administrators said, “Results for all locations indicate that the lead levels are below the EPA recommended action level and all locations are safe for consumption.” Finn wrote, “I hope that this additional information provides a level of comfort … the water sources tested in this phase are all safe.”

Lois Stanley, the vice president for campus operations, was cc’ed on this email. Information about September’s lead testing that found unsafe levels of lead in water sources in multiple buildings was not communicated to the general student body at any point, nor was the information that EHS sent out to school and department administrators in October about the results of the follow-up in other water sources that found lead levels to be safe in these locations.

Some students have criticized the school’s lack of communication with students about the ongoing testing and fountain closures. “It’s ridiculous,” said Maddie Silverberg ’24. “Everyone knows this is a problem but we haven’t gotten a formal document from the University saying what they’re doing or where to avoid.”

In his brief to the Justice in December Finn stated, “Our third round of testing confirmed that sources away from the bubblers were/are safe,” to which the Justice asked what assurances students have that the affected fountains will be safe to drink from once they are replaced. On Jan. 26 he wrote back: “Once Facilities Operations gets things replaced, yes I will do another round of testing at those locations [to assure the water’s safety].”

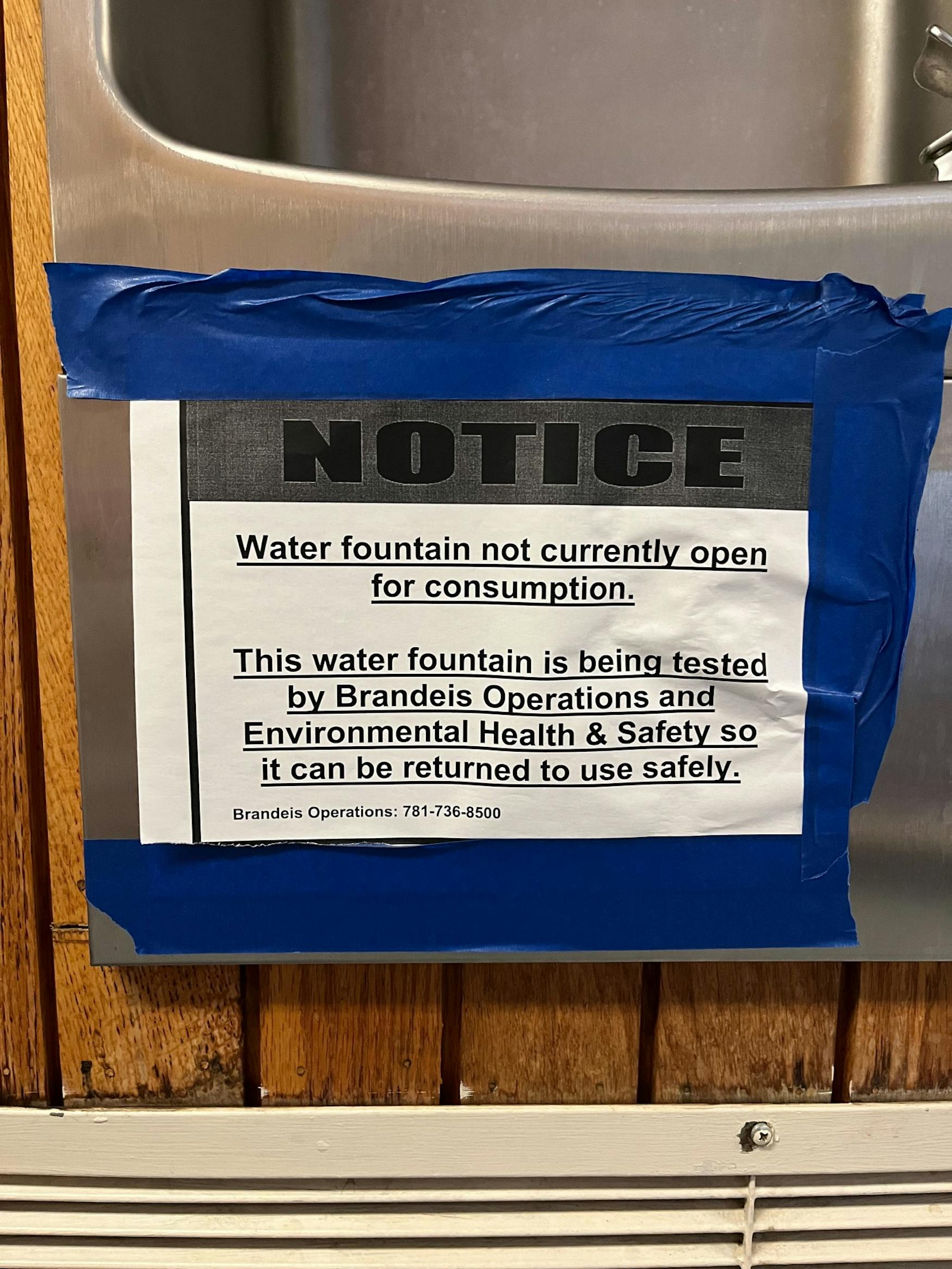

Besides the Brown building and Edison-Lecks, no other buildings have been “identified as areas of concern,” Finn answered in response to the Justice’s question of whether students should be made aware of any other buildings testing positive for lead. “My understanding is that … water fountains that were identified [as testing positive for lead] have been shut off and continue to stay off or have been physically removed,” he stated. In Brown and Edison-Lecks, units remain off or have warning signs attached.

Farber fountain closures

The Justice asked Kabel explicitly about the library’s drinking water, in addition to asking about the Brown building. “In response to your request directly … the Brown building was identified as being at risk,” Finn said on Kabel’s behalf. The request for information about whether the library was part of the testing program was disregarded entirely.

In his Oct. 22 email to school and department administrators, Finn said that testing performed on the sink in the bathroom on the first floor of Farber determined that water from this source was safe to drink. The water fountain directly outside of this bathroom remained on, with students using it, for another week. Thom Valcemetti, one of the library’s public service coordinators, spoke with the Justice on Nov. 10, explaining that, “A week ago [week of Nov. 1] Facilities came and turned off the water fountain in Farber 1.” A sign was put up on Nov. 10 instructing students not to drink the water. It was gone by the following afternoon.

Rafi Levi ’24, a student library worker, spoke with the Justice on Jan. 28. He added that the water fountain on the third level of Farber, adjacent to the Sound and Image Media Studios, had been out of commission since the beginning of the fall semester, and added, “There was a time towards the end of the fall semester that all three fountains were turned off at once. We had to walk to Usdan if we wanted water.” The SIMS fountain remains off with a warning sign, similar to those in Brown and Edison-Lecks.

Kabel explained in the Sept. 22 email that “Although you might see some random water fountains turned off throughout campus, there could be many reasons for this. Sometimes the issue is a broken part, sometimes it is an isolated problem that can be fixed by replacing a fixture or fountain, and sometimes it is just waiting for test results to return.”

This information suggests that contaminated water is not necessarily the reason for fountains being closed and would likely be reassuring to students. However, the majority of the student body — including student workers in the library, where multiple fountain closures have occurred over the past months — have not been made aware of this or received any explanation about testing practices and a variety of reasons for fountains being shut off. When asked how he felt about the University’s lack of communication regarding the fountain closures, Levi said, “Like the University doesn’t care about the students or any of the people affected.” Student Union Senator Sofia Lee ’24 echoed this sentiment in a Jan. 28 correspondence with the Justice: “I’m definitely very concerned with what’s happening with the water filters as a lot of people don’t feel safe using them.”

Valcemetti said he was unaware that buildings around campus were being tested for lead: “When Facilities came to turn off the water [in Farber 1] they didn’t tell us anything except that the fountain had ‘failed inspections.’ At this point you students know as much as we do.”

Timeline unclear

EHS is taking procedural steps to addressing the buildings affected by lead, which they explained in their brief to the Justice. In an Oct. 14 article in The Brandeis Hoot, Kabel was quoted as saying: “Facilities and Environmental Health and Safety tested the water to ensure our levels were within standards after being idle so long in order to protect our staff and students. When levels were high, we took action accordingly. The safety of our students and staff is our #1 priority and this is one step we take to ensure it remains our priority.”

Finn ended his brief to the Justice by explaining EHS and Facilities’ plans going forward: “Extensive flushing of the lines was also done which is an acceptable and generally one of the first corrective actions in this case … one of our biggest hurdles at the moment is the lead time on getting new equipment, but it is in process.”

There is no clear timeline as to when this will happen, though, and supply chain backups are out of both EHS and Facilities’ control. A student worker at Facilities said the same, explaining it currently takes up to two months for a manufacturer to send a replacement part. “Sometimes we even have to use eBay,” they added. Supply chain issues notwithstanding, the student facilities worker added the office’s own delays in addressing fountain repairs: “Our office [Facilities] is insanely disorganized,” they said. “When something happens with a water fountain and I assign a plumber to it, it could be a week until someone actually looks at the [work] order.”

“They are planning to do major renovations on our building [Brown] beginning April, and so we all will be temporarily removed from our offices by around April or May through at least December 2022,” Prof. Lamb explained. The student worker at the Brown building psychology lab said that psychology lab operations have been temporarily moved out of the Brown building, with no definite timeline of when the fountains will be replaced.

Communication concerns

With students having received no statement on lead testing results and fountain closures from the University, rumors about contaminated water — based on the limited information provided to some students and speculation prompted by the warnings taped haphazardly to various fountains — have been floating around the student body over the course of the school year. “We’re already trying to stay safe in a global pandemic. To be at a school with a $75,000 tuition and feel unsafe in basic health measures is very worrying,” a neuroscience major from the class of 2024 told the Justice on Jan. 31. While not as worrying to her as the lead itself, the student said she finds the lack of communication from the school about lead levels and closed fountains concerning. “It makes it seem mismanaged. At the end of the day, all we’re asking for is transparency. No one would blame Brandeis; lead isn’t in their control. Communicating [to students] is.”

Noah Risley ’24, director of communications for the Student Union, said, “The Student Union has continually brought up the communication issues with the University and looks forward to seeing progress this semester.”

Whether the University will communicate with the student body once the fountains are replaced by Facilities and re-tested by EHS — and bring to an end to the continued radio silence that concerned students have received from their University administration up until this point — remains to be seen.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.