University welcomes photographer for “ArtiUnst Talk” event

Nadiya Nacorda discusses her projects and answers questions from students.

On Wednesday, Oct. 20, Brandeis welcomed artist Nadiya Imani Nacorda via Zoom to talk about her experience as an artist, namely her work as a photographer. During the event, Nacorda explained and shared photos from a few of her projects and answered questions about her work.

Nacorda, born in Detroit, Michigan, is an artist who “works in photography, video, and performance, to address matters of intimacy, affection, displacement and identity as a child of immigrants,” according to her website. She earned a BFA in Photography and Film from Virginia Commonwealth University, and she is currently finishing an MFA in Art Photography at Syracuse University’s School of Visual and Performing Arts. She was a 2019 finalist at the Magenta Foundation’s Flash Forward competition, the 2020 Lit List and the 2021 Silver List.

Nacorda began the “Arts at Brandeis” event by presenting the first few photographs that she took when she was a teenager. She explained that she started out as a family photographer and a “family documentarian.” The photos serve as a “marker of time.” She focused mainly on her two youngest siblings, documenting them growing up, saying that it is “particularly important for Black families to have deep archives of documentation of just everyday life.” She went on to say that photos of Black families do not have to be “overly exaggerated,” and that they can be of what she described as “everydayness.” She explained that growing up, she didn’t see images of families that looked like hers that were just about life and what it means to be human.

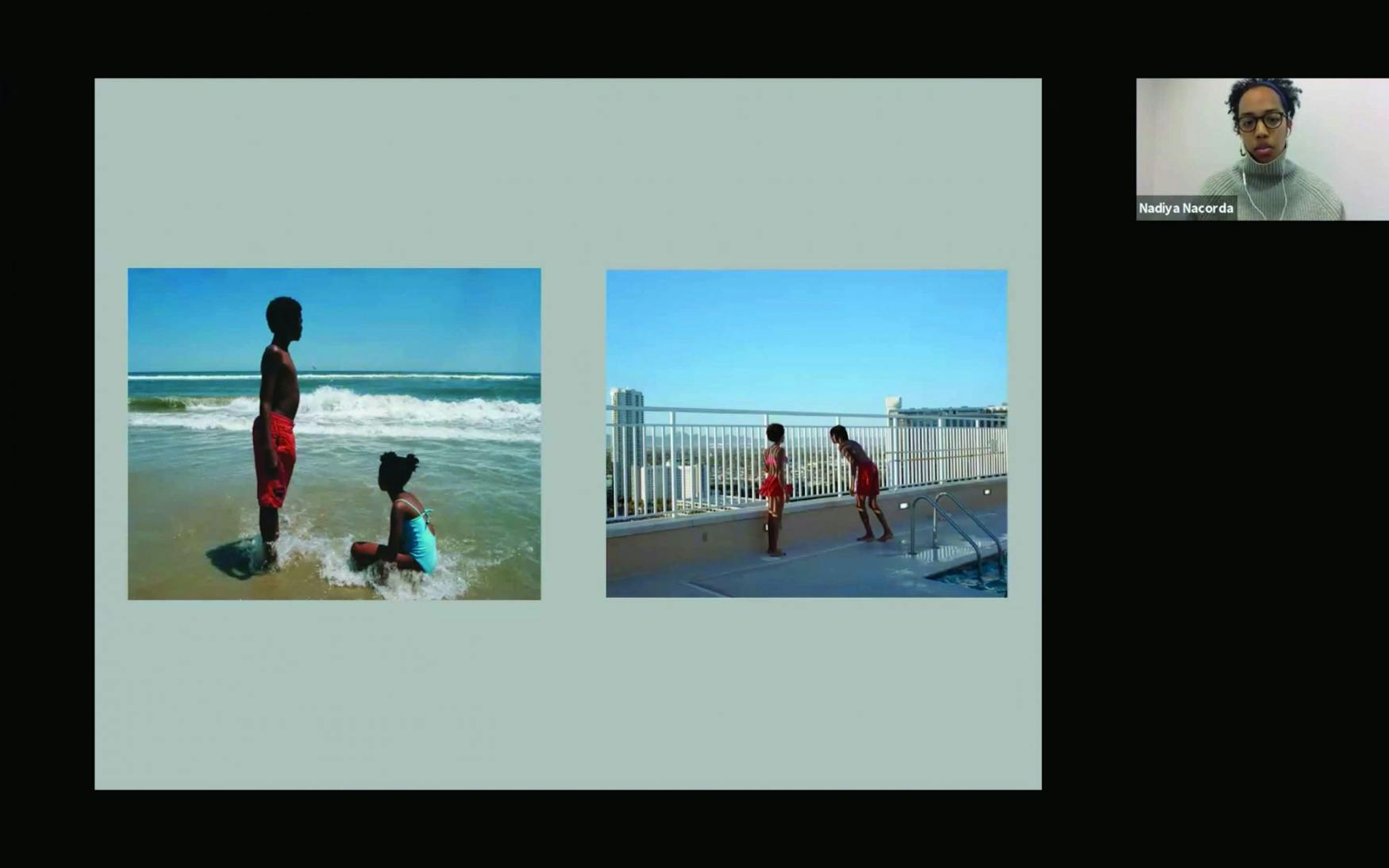

She then talked about her first project, “A Special Kind of Double,” whose title is taken from a Toni Morrison quote. She continued showing images that she’s taken of her two youngest siblings, who she is still photographing to this day, roughly 15 years later. The photographs ranged from joint shots such as her sister holding onto her brother’s arms, or individual portraits of each sibling. Many photos were taken at places like the park or the beach. Nacorda explained that it’s fun for her to see these shifts in time, as the collection of photographs range so many years, and the photos also make her think about what it means to “document Black kids in America in positions of play.” When her siblings were young, she would often take them to places of recreation, and this theme has continued. She likes taking photos of them in places where they can “just be.” She said, “Black youth — often are deprived of their innate innocence,” so her photos paint a youthful portrait of Black youth youthfulness that is “often not allotted to them.”

Next, Nacorda discussed her latest project, which focuses more on her family and family history and is largely based on her identity as the daughter of immigrants and political refugees. Her father’s side of the family came from the Philippines in the late 1970s, and her mother’s family, who were anti-apartheid activists, came from South Africa in the early-to-mid 1960s. Her parents divorced when she was at a young age, but she grew up close to both sides and became “ingrained in both cultures.” She looked back at family archives and included some photos of her own to create her project, “All the orchids are fine.” The title itself was taken from the caption of an old polaroid of her family’s. The project includes old images of her grandmothers, parents, her as a child and newer photos involving multiple generations, such as the one she showed of her maternal grandmother and her sister. While the older photos were all a smaller size, the photos conveyed a sense of what Nacorda referred to as “timelessness.”

Nacorda answered some questions from students near the end of the event. She discussed many topics, including ones about her work as an artist and others about her identity as Black and Filipino. One individual asked if there were any negatives to pursuing an art degree. Nacorda explained that there were many negatives for her, including a “stifled sense of excitement” and stifled “willingness to experiment without fear of the outcome.” She also said that since a lot of her work hinges on her identity, critique rooms were often unhelpful as white individuals would have nothing to say about her work focusing on Black youth.

She also shared that she was influenced most, not particularly by famous photographers, but by her friends, and that she wished she’d known not to take herself and her work so seriously when she was starting to take photos. “I think if I had done that, I wouldn’t necessarily be in a different place, but I think I would be maybe here a little bit sooner,” Nacorda said.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.