Poptimism: an outdated term

For modern pop music criticism to actually be modern, poptimism needs to be retired.

Poptimism was a term coined in the early 2000s that went hand in hand with a heel turn made by critics against previous notions that pop music was inherently not worth critique. It instead dictated that pop music was just as worthy of an in-depth analysis as any other genre. Poptimism has been one of the most impactful critical movements of the new century: over the course of the 2000s, publications like indie tastemaker Pitchfork went from reviewing a Kylie Minogue as an April Fool’s joke to putting one of her songs in the top 40 of its “Best Songs of the 2000s” list.

In the years following, poptimism has not been without its detractors. Saul Austerlitz, for example, wrote a piece for the New York Times Magazine in 2014 decrying poptimism, asking “Should gainfully employed adults whose job is to listen to music thoughtfully really agree so regularly with the taste of 13-year-olds?”

The detractors have then inevitably been met with detractors of their own. Maura Johnston, for example, responded to Austerlitz by writing a piece for Vice with the headline “The New York Times Doesn’t Know Shit About ‘Poptimism,’” saying, “[Poptimism is] about throwing out the artificial distinctions that elevate Serious Mass-Appeal Music (usually made by men, and with guitars) over Frothy Bubbly Stuff (which often appeals to women as much as, if not more than, it does men)... [it’s] about understanding that the underlying musical complexities of Britney Spears’s ‘Toxic’ can be as intricate as, say, those lurking within Jellyfish’s ‘New Mistake.’”

This process, of poptimism being supported, then attacked, then defended, rinse-repeat, has been the way that music criticism has been operating for the entire time I’ve been reading it, and as a Gen-Z reader, I’m bored. This conversation is not only tired from over-discussion, but it’s outdated too. Articles have been published by major publications in the past decade declaring poptimism everything from untruthful (2015) to dead (2017) to feminist (2018) to tribalist (2021). Yet, poptimism doesn’t feel relevant to any world I’ve lived in since I was in elementary school and Lady Gaga burst into the scene.

As this conversation continues to make the rounds, this year and for what feels like likely every year after that, it ignores the fact that the music industry has changed. When the poptimist debate began, radio was a dominant force in the music listening public. A song could be omnipresent to the point where everybody knew the words, whether they wanted to or not. From Britney’s “Toxic” to Nelly’s “Hot in Here” to Gaga’s “Poker Face,” the songs of the 2000s were the last gasp of musical water cooler talk, something you could discuss with everybody you knew and expect they’d have the opinion.

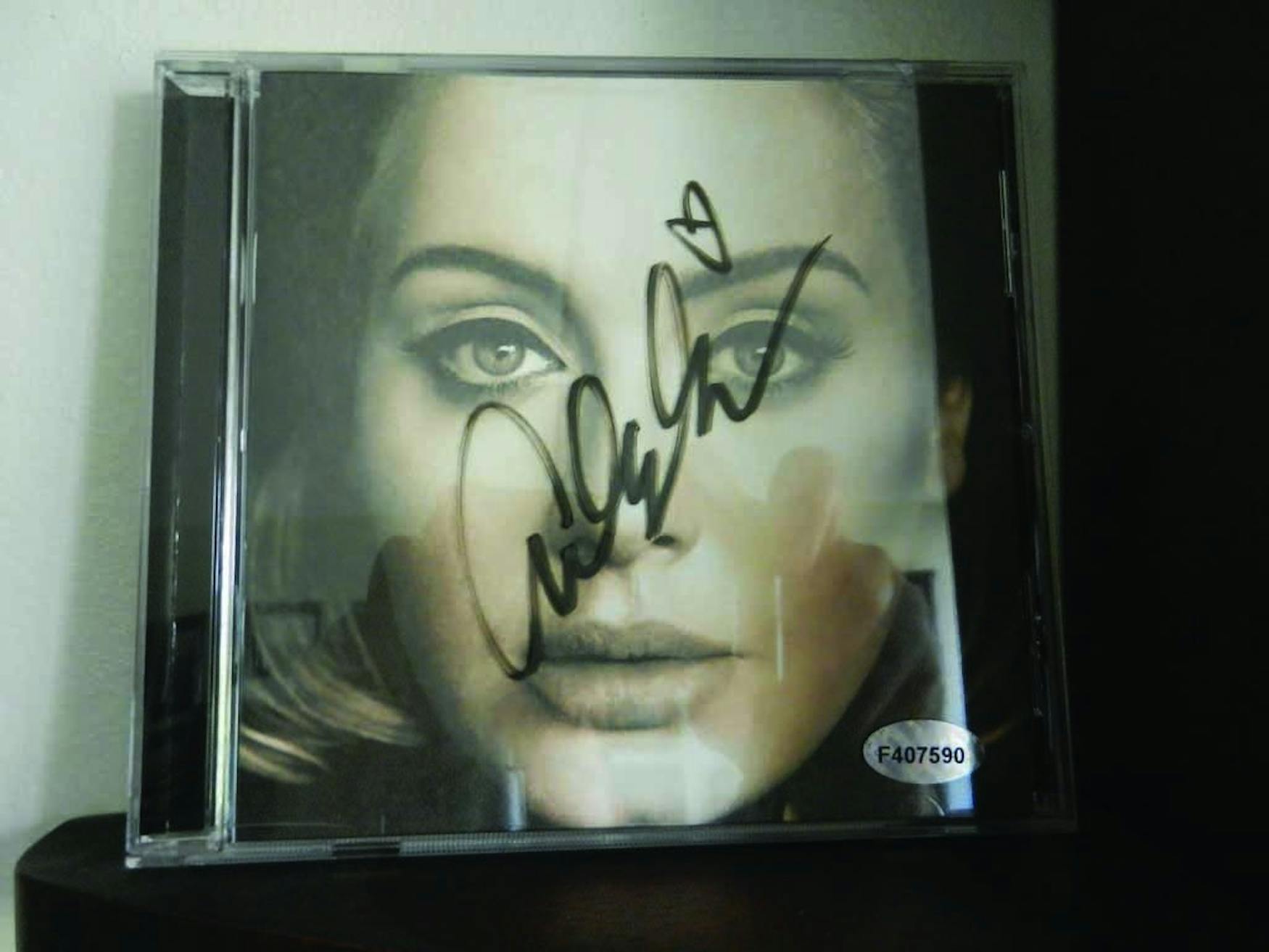

Streaming has changed that. Instead of relying on the radio or MTV to introduce them to new music, people can listen to music that directly appeals to them and only hear new music when they want to, in genres they already like. Recently, Adele’s first new song in six years, “Easy On Me,” broke the record for the most streams on Spotify of any song in a single day, yet if someone told me they hadn’t heard it, I wouldn’t be surprised. Streaming allows the general public to listen only to what they like, whether that’s pop favorites like Drake and Ariana Grande, or weirdos like The Mountain Goats and FKA Twigs.

That type of conversation, about omnipresent artists who no longer seem to exist, is what poptimism was purporting to fix. It was initially created as a response to “rockism,” the perspective that previous generations’ music was always better than what’s current. But what’s “current” is entirely up for debate.

Simultaneously, the genre of “pop” itself is wildly shifting. In terms of what is actually “popular,” pop has ceded its throne largely to hip-hop, with diverse artists like Megan Thee Stallion, Drake and Lil Nas X all regulars in the top spots. Pop itself has gotten weirder in the time since poptimism was coined. Indie pop, a phrase that would have been a strange oxymoron in the ‘90s, has exploded in popularity, with artists like Robyn, SOPHIE and 100 Gecs making music that purported to be “pop music” without any goal of making it onto the charts.

Is poptimism supposed to apply to these artists? Would critics have responded to Megan Thee Stallion’s rap smash “Savage Remix,” one of last year’s best songs, so positively if we weren’t still talking about poptimism? Would they be able to wrap their heads around SOPHIE’s groundbreaking album “Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides” if poptimism wasn’t part of the conversation? Of course they’d get them, as long as the critics have any value. “Savage Remix” may have been popular, and “Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides” may have been pop music, but neither resembles the Kylie Minogue music that was fighting to be taken seriously when poptimism was coined.

What we’re left with, then, is a mode of criticism that is responding to a culture that no longer exists. What’s keeping poptimism alive isn’t the music, but the continued critical conversation. There is no universal pop music fighting for critical acceptance anymore, so the choice to take poptimism as an idea seriously is irrelevant. The issue is not that poptimism is good or bad or feminist or tribalist, it’s that it doesn’t matter.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.