The Flesh in Question: A Response to Orientalism and the Male Gaze

In the virtual discussion, “The Flesh in Question,” held on March 16, Professor Ariel Basson Freiberg (FA) engaged in conversation with Stephanie Davereckas, an art historian, curator and critic. Outside of Brandeis, Freiberg is a painter specializing in feminist theory in the visual arts. Her exhibition, “Hellbent,” is currently being shown in a virtual format at Brandeis Women’s Studies Research Center. This particular conversation, organized by curator and Director of the Arts for the Women's Studies Research Center Susan Metrican, examined Freiberg’s exhibit in conjunction with Linda Nochlin's 1983 essay "The Imaginary Orient" and historical paintings depicting the biblical figure of Salome. The paintings showcased in this exhibition feature bright colors, women’s bodies both obscured and revealed, and cultural relics meant to counter Orientalism.

Freiberg was born in Texas. Her mother was born in Baghdad and raised in Israel, and her father moved from Philadelphia to Texas. When she was growing up, her grandmother never traveled to the United States to visit them because her grandfather never thought it was worth it, so the patriarchy became personal to her.

At one point in her life, she visited her grandfather in Iraq, where her family was “before [Iraq] was even Iraq,” Freiberg said. He always kept a photo of her from when she had been in the “Nutcracker” in his wallet. In the photo she was dressed in a harem outfit, half naked. From time to time, he would pull it out to show people and laugh at, because it was so odd to have an image like that of his granddaughter in his culture. Later, when she found the image in his wallet after his death, she realized that she had been orientalizing herself without realizing it. The “Nutcracker” itself was part of the Orientalist movement and sparked her interests in Orientalism. She was also interested in the fluctuation of visibility and invisibility of her identity, reflected in her intermittent exposure to culture which was never fully mastered — her family spoke a dialect of Hebrew, but it was never fully explained to her. She remarked that “painting is both fluid and liquid, perfect for creating a transgressive act.”

Orientalism, as defined by Freiberg, was the West’s way of depicting “the East” — often the Middle East or South Asia — in order to sell “the East” in the 1800s. As they did this, artists took reductions of encounters with “the East,” often having never been themselves but working from writings of descriptions of these places to package these encounters and sell colonialism. Artists glorified images to seduce and pull in the audience; these were images made by the West, for the West. Orientalism is still used today to create wars, sell ideas of white supremacy and undermine the multiplicity of human beings, making “the East” seem like a far off mythic land.

Looking at any painting is an embodied experience. Freiberg hoped to live in the past, paint in the present and play with the relationship between gesture and the illusion of image. Her painting, “Binta with Scissors,” is a perfect example of that relationship. The painting depicts a woman with high heels and hot pink paint. The gestural hot pink paint could either represent “labia flying,” or a gesture of paint covering her genital region. This color in relation to the broad gestures was, for her, reclaiming space from the patriarchal history of painting.

“Between Urartu and Greece,” another painting by Freiberg was a direct response to Orientalism. Urartu was a city in Mesopotamia and is the heritage for Armenia. The bird person in the painting was a biblical relic that she saw in a museum and is used as a cultural signifier to represent Urartu, while elsewhere in the painting, she painted a table with a Greek meander — a pattern always used to represent ancient Greece. This dichotomy depicted the difference in representation between the two cultures, everyone discusses ancient Greece, but no one discusses Urartu. The body in the painting is turned upside down, the head is buried like an ostrich and the legs are flying like the wings of the bird person from Urartu. Although this painting is connected to these two civilizations, it exists in its own universe.

“Between Urartu and Greece” also showcases the humor in Freiberg’s work. “Humor and the body go hand in hand,” she said. It is a coping mechanism to deal with the “self mutilation we do in order to fit into society.” At the same time, the code shifting and is a way to survive. Besides humor, cultural artifacts feature prominently in her work. Like the bird or meander in “Between Uratu and Greece,” many of her paintings feature or highlight various cultural relics, continuing to push back against the stylized and fictionalized relics of Orientalist art. The hiding of the head in the painting and the pink broad strokes from “Binta with Scissors” are examples of the way she focuses on making the unseen seen and the commonly seen unseen. The movement in her paintings either fights or emphasizes gravity. All these components lend themselves to a sense of fiction and almost surrealism.

The conversation was not just about her work, as much of the discussion was comparing her paintings to traditional Orientalist paintings. The first piece of art shown in the slideshow was “The Apparition” by Gustave Moreau. In the painting, a naked Salome dances in front of King Herod with an apparition of John the Baptist’s head floating above her. Salome, the biblical daughter of Herod who demands John the Baptist’s head, is seen as a symbol of a dangerous, seductive woman, leading men to their deaths. The idea of dangerous women coming into and possessing themselves is a broad topic that is addressed in much of Freiberg’s art. Another painting which was shown in relation to her art, was the traditionally Orientalist painting “Snake Charmer” by Jean-Léon Gérôme from 1879. The painting shows a boy holding a serpent, looking objectified and vulnerable, depicting the sacrilegious and dangerous nature of the East. Light is falling on the boy and the audience in the painting. The audience is fully clothed while the performer is naked. All of the figures are being acted upon as the viewer acts as an audience member alongside the audience represented in the painting. The subject is exposed to only the painting’s audience, however, not to the outside viewer. The background of the painting is a turquoise, Islamic-style mural of decorative script. The script is gibberish, but is meant to represent Arabic, a cultural signifier, telling me, the viewer, where this is taking place.

Freiberg’s painting “Flame Thrower” is in direct contrast to “Snake Charmer.” Light is coming from the body while the body in the painting is acting on both the painting and the space. The character in the painting is a trope of a sexual being with “erect fire growing out of her vaginal area,” celebrating creation and transforming the canvas with color and light. It evokes the idea of speaking with different parts of our bodies and creating a cataclysm in a space, like Salome, about taking control and leading men to their destruction and death. “Queef” is painted in a similar way, but instead of flame, pink smoke exudes from a grey figure, becoming part of the atmosphere instead of actively changing it. The pink is like body fluid, Freiberg said — “you can’t not see it.” We are trained to ignore these things, but Freiberg is doing the opposite in this painting by following the idea of the transgressive act and transgressive body.

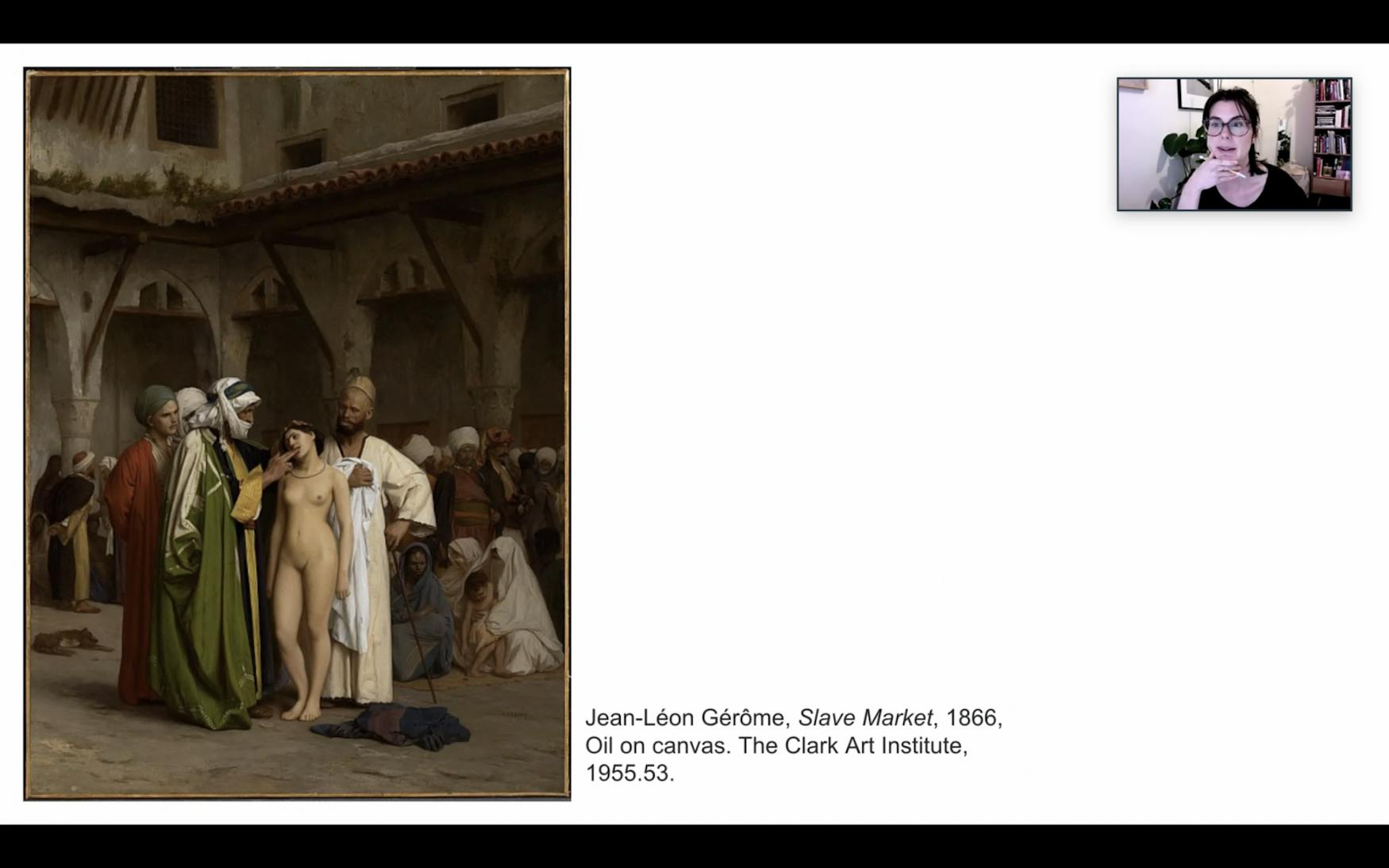

Going back to Orientalist art, the “Slave Market” by Jean-Léon Gérôme from 1866 illustrates the literal and figurative ownership of the female body, specifically showing men possessing women's bodies. This painting caters to the male gaze and creates more alternative Oriental fantasies of the dangerous and sacreligious East. Freiberg’s work, “Hermaphrodite Mind,” breaks away from tradition. Her piece explores the idea of the body inhabiting both sexes as she explains that the “mind doesn't have a concept of gender.” The painting uses traditional sexual tropes of a fixed femme figure lounging in space, while the figure is breaking boundaries of the canvas. Broad gestural strokes exuding from both the head and the genitals show the body as a vessel that cannot be contained. It is a spectacle — it is sexually charged and yet it is trying to repel the kind of gaze that naked women in traditional museum paintings invite — the invitation that they are “ready to be taken by the viewer.”

I thought this discussion was fascinating. The audience was mainly composed of other artists from all over the country, although some students did attend. The fact that the audience were other artists lent itself to a complicated and illuminating Q&A session.

The discussion portion of the conversation was a fresh take on Orientalism and feminism, an important critique of classical representations of women and culture that acknowledged the period’s predominantly negative impact on society, the fictionalization of the East and the sexualization of women. The Q&A session raised a lot of excellent points. One of the most important points was the continued issue of Orientalism. In 2019, the “Slave Market” painting showed up on buildings as right-wing propaganda. This usage was following large amounts of immigration as if to say, “See? This is what will happen when Germany becomes ‘Eurabia’,” continuing the narrative of how “superior” and “cultured” Europeans are as opposed to “the other.”

The art was, of course, beautiful. The striking colors and the sumptuous depictions of the female form in relation to the confident and intense strikes of gestural paint are captivating, while the unrepentant and unabashed positions of both the bodies and the paint create a sense of embracing a kind of sacrilege.

Right now, especially with all of the anti-Asian racism in the United States, it is even more important to push back against Orientalism. Orientalism can be seen in descriptions of the Middle East, especially in relation to wars, as seen in Germany, the anti-immigrant sentiment and now the result of COVID-19-related anger. The male gaze has always been an issue— victim blaming women to cover themselves to prevent men from getting erotic thoughts. After the murder of Sarah Everard in Britain, to which the police’s response was to tell women to stay inside for their own safety in an environment where women seem to have less and less control over their own bodies, art like this promotes women as not inherently sexual objects. Women can be sexual, but that is not the point. It should be women’s choice to present themselves as sexual or not. This exhibition shows off the beauty of women’s bodies, celebrating the ability of women to create and influence the spaces around them, while also addressing the very real issue of Orientalism.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.