Professor from Ca’ Foscari University of Venice presents work on Jewish Venecian ghetto

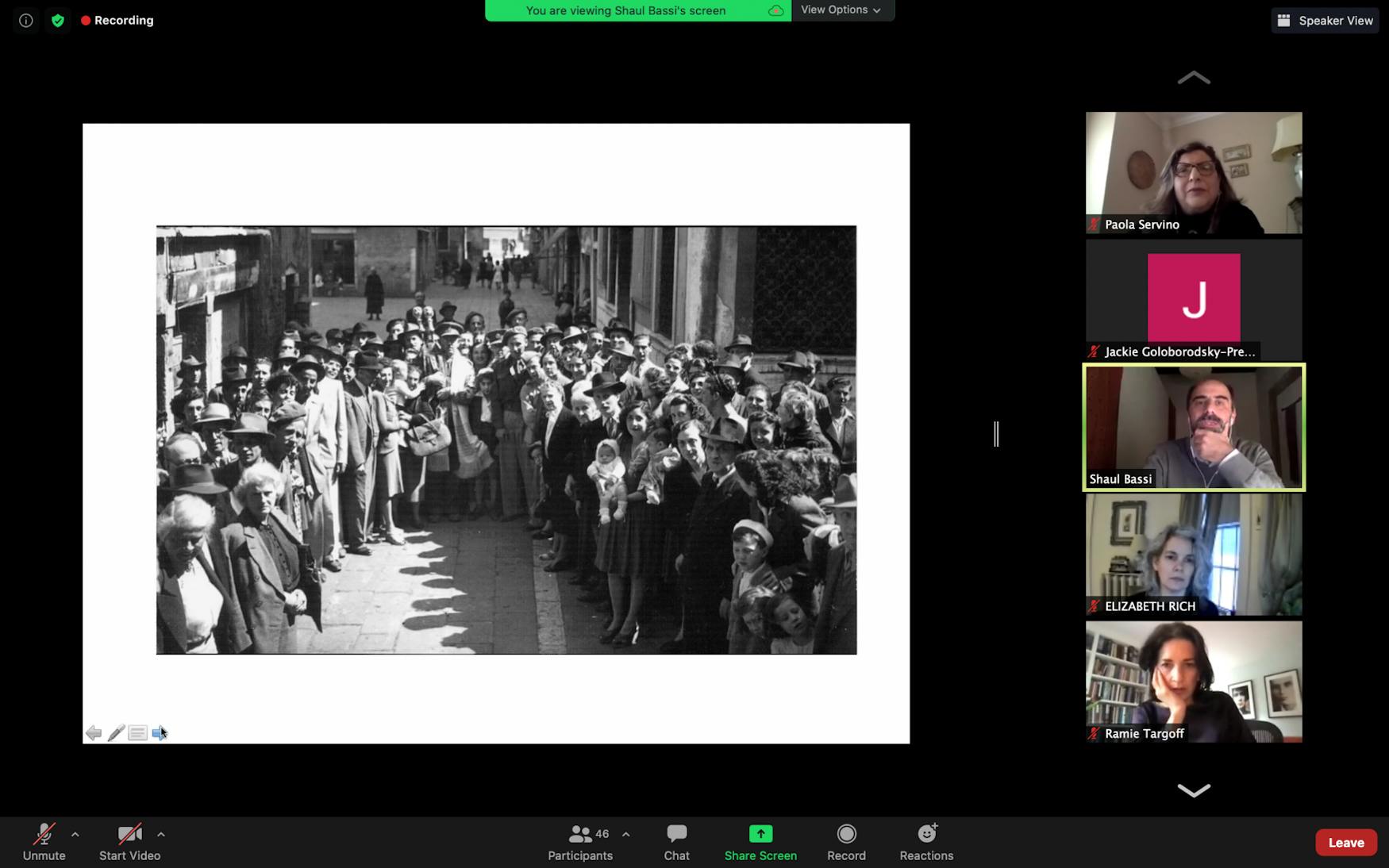

Professor Shaul Bassi emphasized the significance of the Jewish community that once lived in the Venecian Ghetto, as well as the present day value of the Ghetto

The Brandeis Interdepartmental Program in Italian Studies hosted a talk featuring Shaul Bassi, a professor of English Literature at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy, to virtually present his work about the Jewish Venician Ghetto on Mar. 3. Brandeis Prof. Paola Servino (ITAL) and Prof. Ramie Targoff (ENG) introduced Bassi and his influential work for Italian Jewry.

Bassi’s work revolves around “reconceptualizing the Jewish ghetto of his childhood.” While the word “ghetto” is defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “a quarter of a city in which members of a minority group live especially because of social, legal, or economic pressure,” it has not always been the global word for segregation.

Bassi explained that the name “ghetto” first came from the Venecian word “gettare,” which means to pour or cast, and was the name of an abandoned factory where the Venecian Ghetto would be established. The Venecian Ghetto led the Pope to coin the term “ghetto” for all Jewish segregated quarters. The word then traveled through “tragic episodes and historical moments before it became the name for ethnic enclaves,'' Bassi said. The first ghetto, Ghetto Nuovo, was established in 1516 and in 1797 Napoleon burned down the ghetto gates. In 1866, Jews became full citizens of the Italian nation state and for almost 70 years, Italian Jews were equal members of society: “they shed their Hebrew names for Italian ones, fought for Italy in World War I, and many, including some of my own family, even joined the Italian Fascist party,” Bassi said. This equality ended when the Nazis established rule over Italy and expelled Italian Jews from their homes.

The Venecian Ghetto was not the first Jewish ghetto, but it was the first place where “ghetto” became synonymous with Jewish segregation. It was a mosaic of different Jewish communities that blended with local Venecian society, creating a multicultural and multiethnic Jewish community.

Many paint the residents of the ghetto as passive victims, but Bassi’s work tries to show that this was only a cover for the true culture of the ghetto. “A place of fierce debates, passion and fury. A place where Jews felt confident,” he said. While the ghetto placed limitations on Jewish life, it also allowed Jews to act freely and fiercely within the comforts of their community. Many first hand accounts from the ghetto show that the Jewish community acted very differently within their homes as opposed to when communicating outside the ghetto. The presentation included quotations from a rabbi in the Italian ghetto’s writings. His public statements “seemed devoid of passion; this was part of the apologetic tradition that Jews demonstrated to keep themselves in the city,” Bassi said, but his personal notes revealed a completely different attitude, one where the anxiety, passion and fury of the Jewish community were felt.

Only 450 members of the Venecian Jewish community remain today. In addition to the decreasing population, another issue that has had detrimental effects on Italy and Venice is tourism. Bassi is the director of the Venice Center for Humanities and Social Change, which works to combat the negative effects of tourism in Venice. The organization’s goal is to make the Jewish ghetto a center for scholars, students, artists and writers. “We need to rekindle the idea of Venice as a city of knowledge,” Bassi said. He concluded his presentation with a plea for people to come to the “aesthetically radioactive” Venice. Unlike the rest of Italy, Bassi has observed that the ghetto is not a mecca for photographers and herds of tourists — it is a place for people genuinely interested in Jewish history.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.