Addressing the Ads

Walt Mossberg '69 spoke about the dangers of advertising, saying it is "destroying the internet."

“Think really long and hard, and if by the end you’re still comfortable with giving over your data to all these companies, then fine. But chances are you aren’t okay with this theft that is taking place.” Walt Mossberg ’69, considered by many to be the father of technology-review journalism, is deeply troubled by what he calls the “theft” of consumer information by internet giants including Facebook, Amazon and Google. On Oct. 22, Mossberg delivered a lecture at Brandeis, his alma mater, on how the “ad tech,” or advertising technology industry, is destroying the internet. He warned that internet users have opted into a grand bargain, and that we are all being ripped off.

In May 2004, Wired Magazine called Mossberg “The Kingmaker,” and for good reason. The son of a salesman and a stay-at-home mother, Mossberg was the first in his family to attend higher education. He chose Brandeis over Brown University, telling the New Yorker that Brandeis was “less stuffy,” and graduated in 1969 with a degree in Politics. Almost immediately after graduating, he took an investigative reporting position at the Detroit bureau of The Wall Street Journal. After 18 years of writing about labor, energy, trade and foreign policy, he turned to covering a new interest: personal computers. At the time, personal computers were still fresh on the market, and their commercial success was far from guaranteed. Mossberg recently told Brandeis Magazine he believed at the time that personal computers would change the world.

Mossberg’s new beat would come to define his career. In 1991, he debuted a WSJ tech column aptly titled “Personal Technology,” written to help make tech gadgets accessible to the average consumer. The column, which ran every week on the front page of the WSJ’s Thursday Marketplace section for 22 years, was one of the first columns of its kind written by a journalist who lacked a background in engineering or computer programming. “Personal Technology” was an instant success.

Instead of focusing on all the features of a new product, many of which Mossberg said consumers rarely used, Mossberg explained how devices were designed and what it felt like to use them during the course of daily life. Positioning himself as a champion for the average consumer, Mossberg’s reviews were predicated on the belief that regular people don’t struggle to use new products because they are stupid — sometimes, tech gadgets are just clumsy and poorly designed. Over two decades, his column rewarded products which were simple and intuitive to use over bulky products that required tech know-how to operate. This included his praise of products like America Online over Prodigy, helping to put AOL on the map. In contrast, a negative review from Mossberg could send a company’s stock into freefall.

While Mossberg’s days as the tech journalist “kingmaker” might be behind him, the veteran journalist’s opinion still carries weight in the tech world. These days, Mossberg’s attention is focused on what he sees as an existential threat to online privacy — “ad tech.” Mossberg’s history with “ad tech” began in 2001, with his scathing review of Smart Tags — a feature in Windows XP that was capable of turning any word on a website into a hyperlink that could lead to another website owned by Microsoft or sponsored by them — without the consumer knowing. Mossberg’s review was so damning that in response, executives at Microsoft discontinued the feature within the month.

Smart Tags were just the beginning. In an interview with the Justice, Mossberg said, “Everywhere you go online, you’re being tracked.” Today, nearly every website, from subscription services like the New York Times to free platforms like Facebook, load lines of code onto their webpages that can identify users’ IP addresses and metadata, he said. Most times, these websites load dozens if not hundreds of trackers, which can include well-known companies like Amazon and Google, as well as more obscure services like BlueKhai or Chartbeat. He explained that both of these lesser-known companies are part of a growing industry that has operated with virtually no government oversight, tracking users online in an effort to gather and sell the information they collect to other internet publishers worldwide. These publishers then use this data to target ads to users based on information such as user location, browser history and online behavioral patterns. According to the search engine Duckduckgo, the Times’ website loads 43 distinct trackers. Even Brandeis’ website, brandeis.edu, allows Google Analytics to track people who visit the site. As of press time, Brandeis Information and Technology Services did not respond to a request for comment on their website policy regarding trackers.

Mossberg pointed out that websites have used cookies, lines of code that store account data, for years to remember passwords and credit card numbers, streamlining user experience on their platforms. “The stuff we are seeing today is more than cookies,” he said. “Unlike with cookies, websites are sharing your data with so many other companies, and you’re not signing off on this — it’s not even in the fine print.” He explained that users can be tracked even once they have logged off of a website.

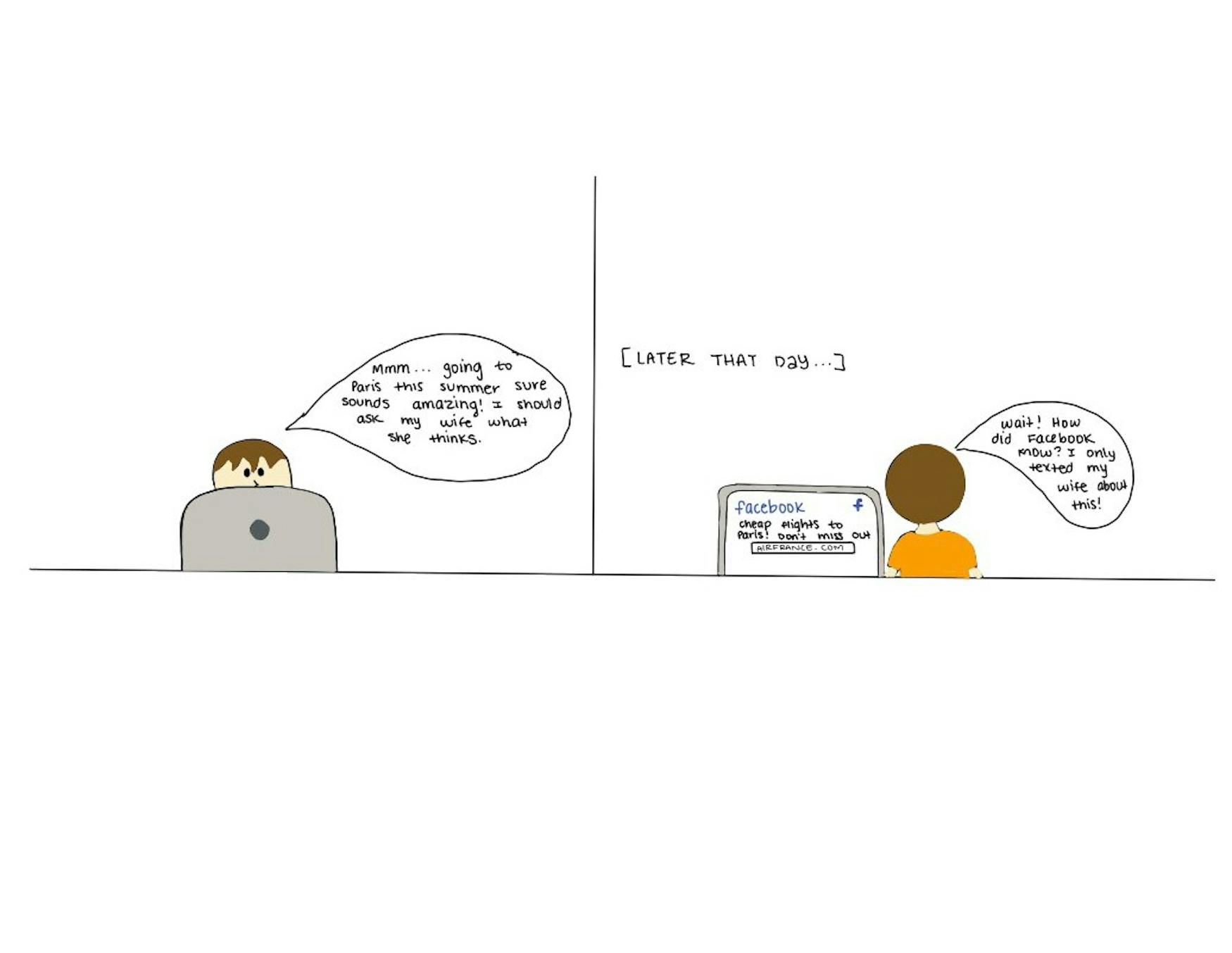

Facebook infamously tracks its users through a variety of methods, but the company is far from alone in these practices. After Mark Zuckerberg was hauled before Congress last year to face questions from senators on the company’s role in spreading disinformation and surreptitiously collecting user data, reports about Facebook’s tactics were met with alarm from internet privacy advocates and tech reporters alike. Reporting in Wired and Buzzfeed revealed that Facebook was able to track users once they had logged off the website by enabling Facebook “like” buttons on third party websites to send information back to the company.

During his lecture at Brandeis last month, Mossberg told a room full of roughly 75 students about “something even more invasive”— Facebook pixel, a piece of code which the company allows advertisers to conceal on their websites by embedding onto a single pixel, usually hidden within an image. When an action is taken on a website, the encoded pixel is triggered to send information about the action back to Facebook. Through tracking, Facebook is able to build a profile on every user, and even on people without Facebook accounts. These profiles can be many pages long, as artificial intelligence is used to analyze even the smallest details of user actions on — and off — the platform. Mossberg pointed out that this data collection is also used on Instagram and WhatsApp, which share the same back-end system as their parent company, Facebook. In an April 11, 2018 article, the Times reported that Facebook was collecting biometric facial data without consumers’ consent. The same article pointed out that even the Times’ website “mine[s] information about users for marketing purposes.”

Mossberg used the term “ad tech” throughout the interview, saying that the “ad tech” industry’s efforts to collect and compile as much data on internet users as possible is in service of a simple goal: targeting ads. “Everyone has a horror story about mentioning a product to a friend or searching for it online only to be bombarded with ads for it moments later,” he said, affirming that this is no accident. Despite all of the data collection, Mossberg argues that the ads we receive aren’t getting any better. He chuckled, “If I buy an expensive winter jacket today, Facebook or Amazon are gonna give me ads for similar jackets tomorrow. Frankly, this is stupid. I’m not at all likely to keep buying winter jackets again and again and again.”

Mossberg’s main argument is that “ad tech” is making our ads “suck,” destroying internet privacy and contributing to the spread of disinformation online. But he says there are a few ways consumers can protect their data. He recommends deleting Facebook, Instagram and Google and surfing the internet using the private bowser Duckduckgo, which, unlike Google or Bing, blocks trackers. “It works almost as fast as Google Chrome and in places of poor connectivity, it’s easy to load a website because you aren’t also loading dozens of trackers with it”, he explained. While these are some simple steps people can take, Mossberg admits that it’s nearly impossible to remain completely private online. Even if a user deletes all social media apps, iPhone and Android phones can be tracked using a mobile advertising identification system, known as MAIDs. While their use is downplayed by phone companies, MAIDs are a string of digits assigned to every smartphone to identify which users are using which apps.

Now retired from writing tech reviews, Mossberg sits on the board of the News Literacy Project, a nonprofit focused on educating a new generation of students to distinguish between facts and false information online. “It’s become very hard to tell what is real and what is fake news online,” he said. Ultimately, Mossberg thinks “ad tech” is the main culprit in eroding everything that makes the internet good. As a solution, he proposes that Congress pass a “real internet law” laying out the principles of privacy that everyone can expect online. In the same bill, he says Congress should create a “nonpartisan and independent commission or court” to resolve internet disputes in a way that the FCC and FTC have not shown they are capable of. Mossberg is purposely vague about the details of such a statute, but says that in an era when a handful of tech companies control all the online ads at the cost of consumer privacy, it’s time for a twenty-first century internet law.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.