Parliamentary gridlock around Brexit is a lose-lose scenario

If you’ve brushed up against any news involving Britain for the past three years or so, you’ve probably encountered and been horribly confused by the never-ending whirlpool of information that is Brexit.

Having just spent the previous semester working in Parliament, I can speak from experience that Brexit has made the British political class and hoi polloi thoroughly miserable, having sucked up every last bit of political oxygen and energy from an already exhausted nation. So how did they get here?

After the 2016 Brexit referendum ended in a narrow victory for the Leave coalition, who do not want Britain to be a part of the European Union, the British House of Commons invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, setting a two-year timetable in which the UK would negotiate its exit from the bloc and leave for good on March 29, 2019.

Prime Minister Theresa May negotiated as hard of an exit as the EU would allow, putting together a withdrawal agreement that would completely sever the UK from the EU’s financial, commercial, immigration and agricultural regulations. Even so, she needed her withdrawal package to pass through the House of Commons, the main legislative body of the Westminster Parliament. How hard could that be?

Three such “meaningful votes” were put up to Parliament and all three ended in embarrassing failures for May and her government. In Westminster-style unitary democracies, governments don’t lose votes unless they’ve completely lost control of their party. May managed to lose more in her 3-year tenure than every single Prime Minister of the past 40 years combined. In their 11 and 10 respective years as Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair lost four votes each: May lost five in March 2019 alone. The first meaningful vote was the largest ever margin of defeat suffered by a government in modern British history, a black eye that would have led to the immediate resignation of most other politicians. Clearly, something had to give and that something was May.

On May 24, Theresa May resigned as Leader as the Conservative Party, opening up her chair position for a new Leader of the Conservatives and by proxy, the next Prime Minister. With the EU consenting to a brief and final extension of the leave date to October 31, the 160,000 members of the Conservative Party voted on who would become Prime Minister for a nation of over 60 million. In the span of a few weeks, former Mayor of London Boris Johnson emerged with a resounding victory.

Despite the initial buzz surrounding the new Johnson government, the parliamentary arithmetic towards passing a with had only gotten worse since May’s failed attempts at a negotiated withdrawal. Although he won with 66 percent of the party’s vote, Johnson is currently working with a voting majority of one, already a major barrier to getting any piece of legislation passed, as a single rebellious lawmaker on the government benches can kill any piece of legislation.

However, this narrow majority is even more tenuous than it originally appears. After a poor showing in the 2017 general election where they lost their overall majority, the Conservatives struck a deal with the Democratic Unionist Party’s 10 MPs to stay in power. Although never a particularly easy partner, the DUP’s status as a hardline Northern Irish Unionist party creates a new set of headaches when it comes to a withdrawal agreement.

Although opposition to May’s deal comes from many angles, the Irish backstop may very well be the thorniest of the bunch. In order to prevent immediate economic turmoil after Brexit, the EU insisted on the inclusion of the so-called “backstop” which would temporarily place Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom, back onto the same rules as the Republic of Ireland, an EU member state. Currently, the UK’s EU membership makes the border a moot point, but after Brexit the Irish border will become a much more pressing issue.

Since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that largely ended the sectarian violence of the Troubles, the Irish border has become something of an afterthought, with goods and people flowing freely between the two sides. The backstop would ensure that this flow can continue uninterrupted after Brexit until a suitable replacement can be drafted and agreed upon.

Fiercely committed to keeping Northern Ireland in the UK, the DUP continue to reject any agreement that would treat Northern Ireland any differently than England, Scotland, or Wales. However, the Irish government and the European Commission refuse to let go of the backstop, fearing an immediate economic downturn and a possible return to sectarian violence. As a result, all 10 DUP members voted against May’s bill all three times. Additionally, any deal including the backstop failed to win the overall support of the European Research Group, a loose coalition of pro-Brexit Conservative MPs whose ranks consistently rebelled against all three meaningful votes.

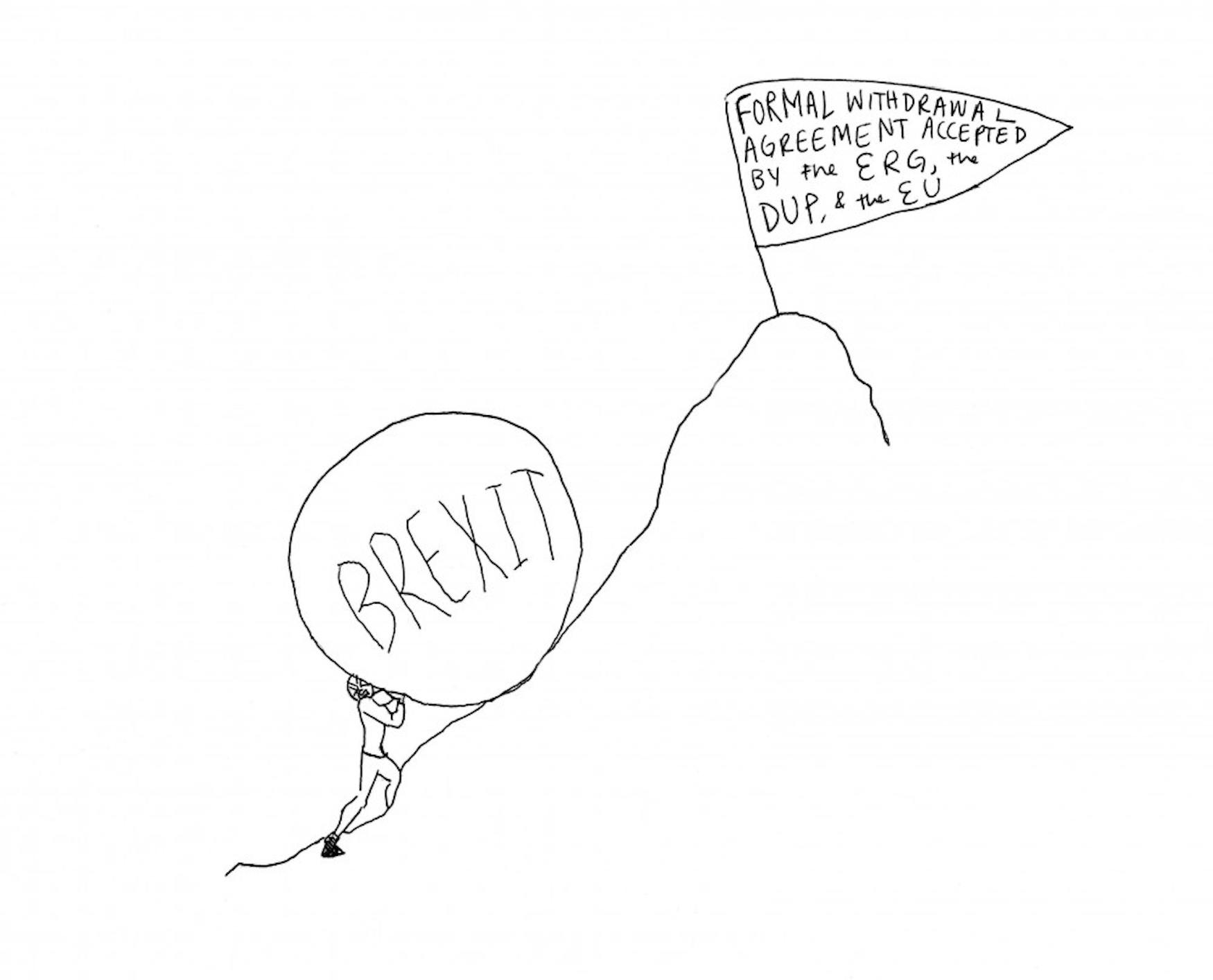

Getting a formal withdrawal agreement that the ERG, the DUP and the EU all find acceptable appears to be a Sisyphean feat, an endless cycle of failure. Additional attempts to get pro-Brexit members of the opposition Labour Party on board proved even more fruitless. With May unable to crack the puzzle, the task has fallen to Boris Johnson, who seems to have solved this Gordian Knot by throwing it off a cliff.

If the Oct. 31 deadline comes and goes without any formal agreement, the so-called “No Deal” exit from the EU takes place as the UK is automatically placed on World Trade Organization tariffs and customs checks, which would devastate the UK’s import and export markets and bring trade with the EU to a temporary standstill.

On Aug. 28, Johnson asked for and received a five week prorogation of Parliament, essentially shutting down any Parliamentary business for the duration. By proroguing Parliament, Johnson has shrunk the miniscule eight weeks rebel MPs had to stop a No Deal Brexit to a mere three, giving his opponents almost no time to act.

While Johnson appears fully prepared to go ahead with the No Deal approach, its effects will likely be disastrous on the UK’s economy and people. Within days, supermarkets will likely run out of fresh food, with their usual imports stranded in an endless line of customs checks. UK pharmacies will run out of essentials like insulin and aspirin by the end of the month. British businesses reliant on exports will be paralyzed, their supply chain gone in a pillar of ash. Worst of all, the crisis and financial uncertainty will likely lead to a credit crunch and financial flight that will devastate the UK’s stock market and housing ecosystem. A No Deal Brexit could be the biggest setback to the British economy since World War II, casting millions into poverty and permanently destroying any hope of Britain returning to the world stage.

So what should be done? Johnson seems absolutely dead-set on the one-two combo of a No Deal Brexit and immediate snap election, intent on riding on the short-term success of finally achieving Brexit before the long-term downturn from No Deal is laid at his government’s feet.

The most ardent of Remainers and anti-Brexit campaigners can only hope for a successful vote of no confidence in Johnson, which would likely hand the reins to Leader of the Opposition Jeremy Corbyn for a brief caretaker ministry with the sole purpose of holding a new Brexit referendum, or scrapping Article 50 altogether. However, the inability of Conservative rebels and third parties to consider a left-wing firebrand like Corbyn as an acceptable Prime Minister will likely put any plans to directly oust Johnson on hold.

Either a cross-party group of Conservative and Labour MPs need to get over the DUP and ERG and pass May’s original bill to spare the UK a No Deal outcome, or a new caretaker government needs to go back to the drawing board and consider a new path out, with even radical options like the revocation of Article 50 put back on the table. The EU has set out its red lines and despite Johnson’s protests, no further concessions will be won. The UK’s future should not be held hostage so that Johnson and his inner circle can advance their political careers.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.