Hong Kong protests should teach democracies a lesson

The democratic liberties experienced in the United States are easy to take for granted. Many Americans are not afraid to voice their opinions regarding the state of the government, the actions of the president, or new legislation that is expected to pass. After all, our current society was formed through the fiery personalities that resulted in long lasting change. These days, the idea of physical protests have transformed into popular Twitter rants. Nevertheless, we aren’t afraid of being threatened or arrested if we criticize the actions of the government. It’s in both our blood and our constitution; but for those currently living in mainland China and Hong Kong, speaking up is equivalent to risking your life.

Over the summer, the political unrest in Hong Kong seemed to resemble the state of America in the late 20th century. The civil rights and feminist movements that embodied much of that time were conceived from minority groups. Although the causes of the Hong Kong riots vastly differ from those of the 1960s civil rights protests, a common theme links the two together: fear that if you speak out against mistreatment, you will be punished. But how much discomfort can individuals handle before they are driven to the brink of insanity? Is it worth risking your life for what’s right as opposed to suffering in silence?

While the reasons behind protests can be complex, they all send the same message: “we are people, we want to be seen, we want to be heard and this is the only way.” Oftentimes, protests beget violence, and that is precisely what is occurring on the streets of Hong Kong. It’s no secret that the relationship between Hong Kong and mainland China is tumultuous. The communist influences of China’s government threaten to undermine Hong Kong’s democracy. Currently, the political upheaval in Hong Kong is largely due to Chief Executive’s Carrie Lam’s proposal of the Extradition Bill, which would allow the Hong Kong government to approve of requests from other countries for the extradition of criminal suspects, including countries that do not have an extradition treaty such as mainland China. Those speaking out against the bill worry that individuals will be unjustly subjected to unfair trials and torture under China’s judicial system. Furthermore, it puts Hong Kong residents who work on the mainland at risk, especially those who document social and political issues such as human rights lawyers, activists and journalists, among others.

Within Lam’s proposal of the Extradition Bill, we continue to see China’s growing influence into the affairs of Hong Kong. The two governments run on differing political ideologies; China remains a communist, totalitarian state, while Hong Kong practices a limited form of democracy. With this in mind, the concerns of Hong Kongers are not dramatized. If they differ in political ideologies, common sense leads anyone to believe that their judicial treatment will differ as well.

As Hong Kongers took to the streets to display their outrage against the extradition bill, the reason for these protests has morphed into something larger. Not only are Hong Kongers furious about the bill, but they want attention brought to police brutality and the state of Hong Kong’s democracy. Protestors want the police to be held accountable for their treatment of civilians as well as an increase in democratic freedoms. Does this sound familiar? This is the same story told in different forms throughout the history of America. Oppressed individuals are tired of the mistreatment they receive from police. The government seems to do very little to resolve the issue, as protesters are being subdued by tear gas, rubber bullets and bean bag rounds like animals, and getting arrested for expressing nothing but their opinions. Do the 1992 LA riots ring a bell? What about the 1963 Children’s Crusade in Birmingham? Or more recently, protests over the tragic deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown at the hands of police officers?

While advancements in society should be praised, we also need to question whether or not we have come far enough. One look at the news shows that recurring issues in history are being brought to the surface and people are tempted to speak out about it. We can use the issues occuring in Hong Kong as an example, but we need not look far because turmoil is brewing right here in America.

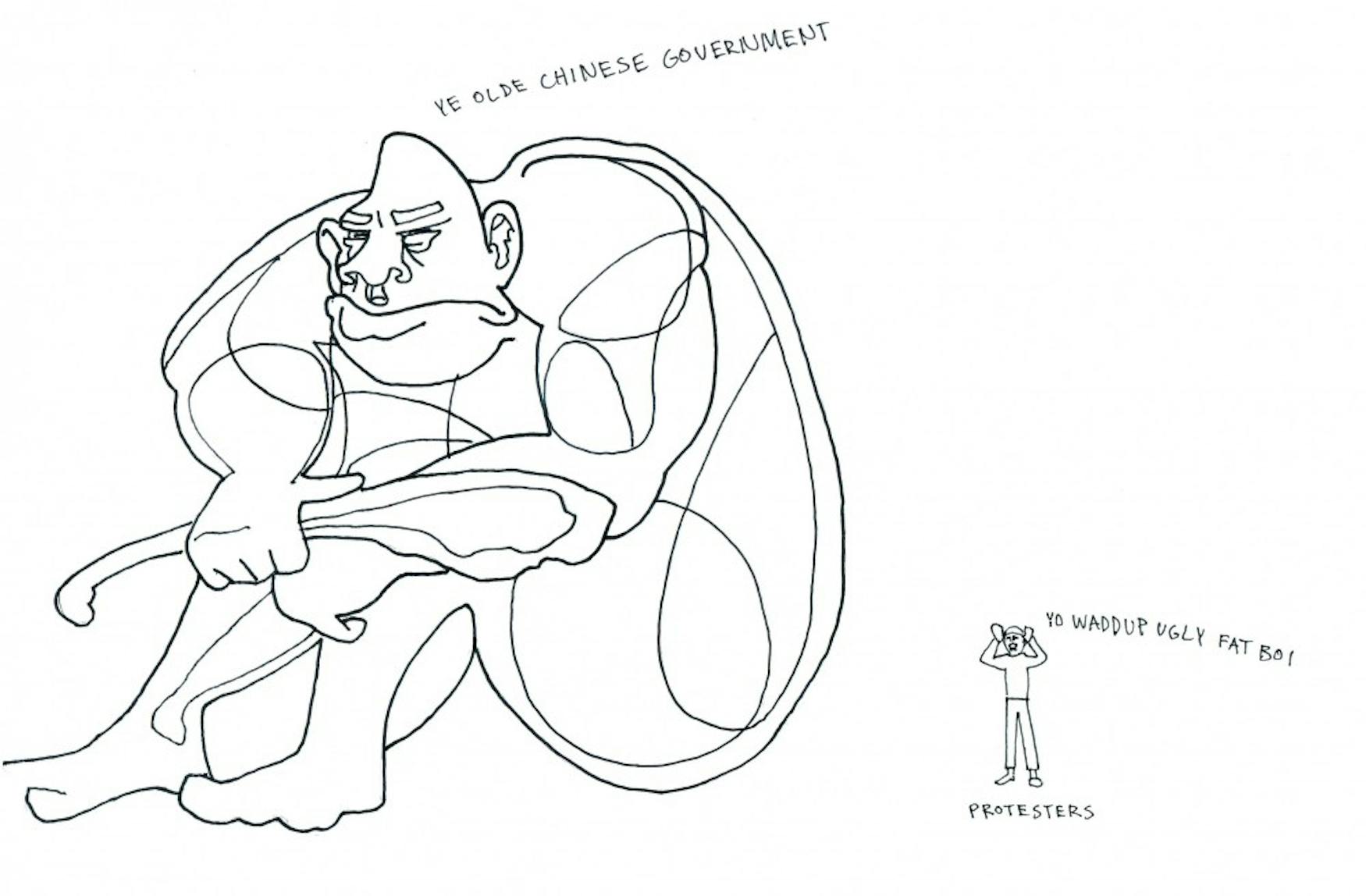

Images are important for relations between countries. So, how are other countries reacting to the turmoil brewing in China’s unruly child? China itself has painted the protests as a symbol of terrorism. Chinese citizens are ill-informed of the protests occurring in Hong Kong against their own government. Coverage of the situation has dubbed protesters “violent” or “criminal” when in reality most of the protests held are intended to be peaceful. A spokesman for the city’s affairs is quoted as saying, “They have already constituted serious violent crimes and have begun to show signs of terriorism.” The Chinese media has negatively portrayed every aspect of the situation in Hong Kong to ensure that there is no chance for support on the mainland to develop. China is used to being in control of all situations and how they are perceived by its people. However, this time the government won’t get its way because protestors are serious about invoking change.

The American and British governments have also issued their own statements regarding the political unrest in Hong Kong. President Trump claims that the Chinese government is going to physically intervene soon. He also says that “everyone should be calm and safe!” and hopes “nobody gets killed.” As for Britain, Twitter has been famously used to convey concern. A member of parliament, Tom Tugendhat tweeted, “This [offering Hong Kongers full citizenship rights] should have been done in 1997 and is a wrong that needs correcting.”

As the Hong Kongers took a page out of our book, should we take a page out of theirs and continue to protest until we get the treatment and respect we deserve from the establishment? Protestors have requested that Carrie Lam withdraw proposal of the Extradition Bill and resign from her position. On Sept. 4, part of that dream became a reality when Lam announced an end to the Extradition Bill. She claims to have done this largely to calm the anger of the masses. Many protesters have labeled this action as “too little, too late,” which begs the question, will the Hong Kong government ever satisfy the desires of the protesters, or will the riots continue until they do?

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.