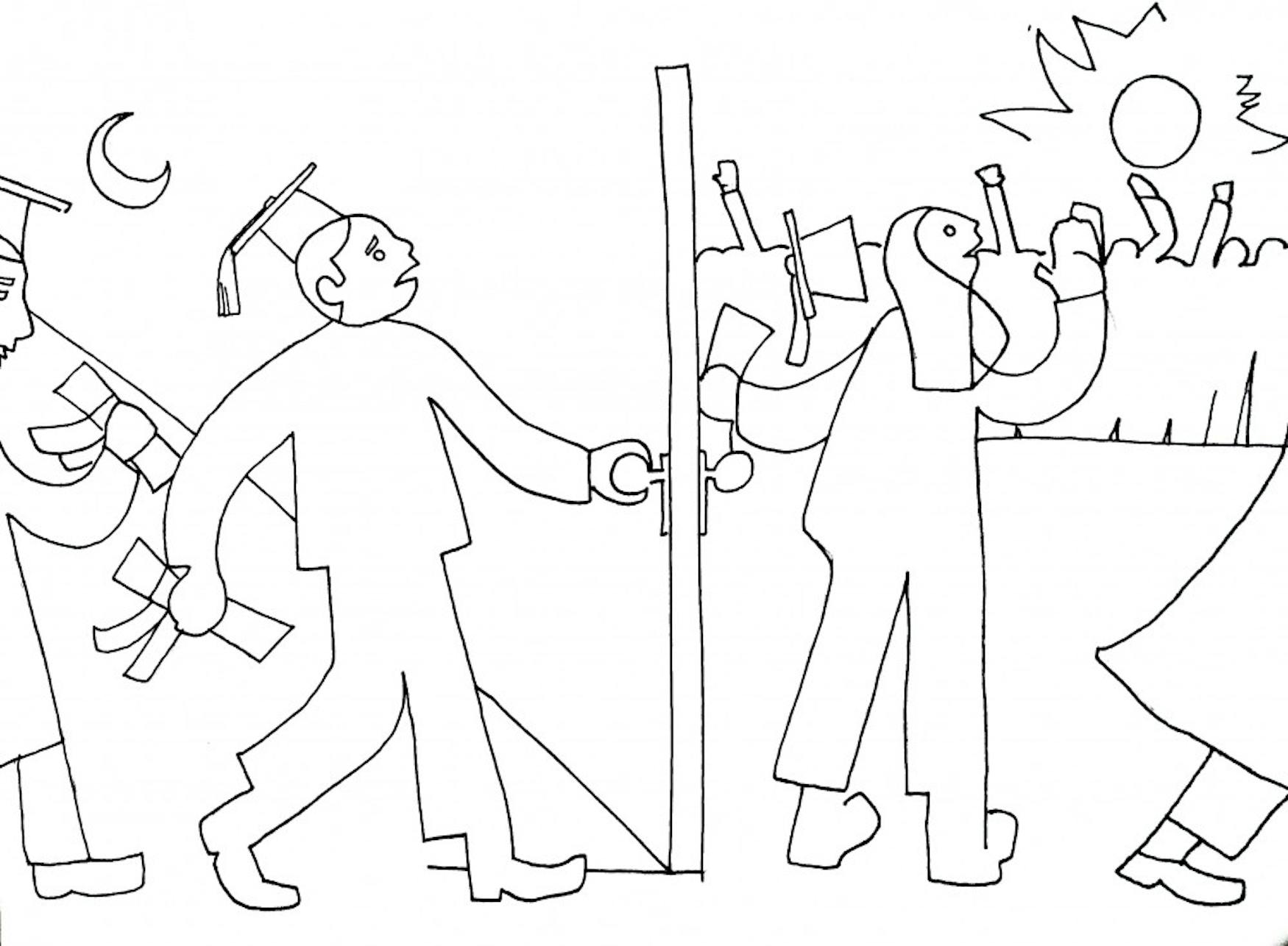

A graduating senior looks back

It’s a daunting task, writing my final article for this paper and avoiding the cliches that characterize graduation season. Am I meant to summarize or galvanize? Clarify or edify? Leave some parting words of wisdom for a generation slightly more addicted to their phones, or express my gratitude for the village of students, professors, friends and mentors that made it all possible? In the spirit of indecisiveness, I choose it all.

To start, I would like to thank my teachers, especially Professors Sava Berhané, Stephen McCauley, Mike McKay and Steve Whitfield. These people are truly excellent educators. In their own way, each taught me to see the world anew. Not only are they subject matter experts, but developers of people who helped grow my knowledge, courage, empathy and passion.

Thank you also to my parents who supported me throughout, and my two little brothers for whom my love cannot be expressed in words. And my friends — thank you for always encouraging me to be me.

Now, enough about me. In the vein of advice, I want to say a few things.

The first is, be okay with uncertainty. College is a time of building ourselves. Done right, we try many things and fail often. We figure out our friends, our interests, our hobbies and values. Inevitably there always remain questions unanswered. This, says poet Rainer Maria Rilke, is the goal — in fact, the whole enterprise itself:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

Another point: be sensitive to the disturbances in your heartbeat. When it speeds up, when it slows down — these are voices of clarity trying to clamour to the surface of our minds like beautiful weeds through the cracks in the sidewalk. We must heed them, listen to them, respect them — because they are the signal among so much noise.

College for me, and I imagine many of you, was a project of convergence — a process of trying to bring closer our inner world and the one outside, one which can be tolerable but is sometimes brutal. When should we trust ourselves? When should we our trust in others? I think what we each need is a healthy dose of skepticism — the ability to ask ourselves, “Is the status quo the best it can be?” If it’s not, we need to seek and find what is.

But this skepticism cannot be unconditional. Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson talks about the process of becoming cynical. He says that most of us begin naive, get burned a few times and then become cynical. I think our generation likes being cynical. We think it’s the most wise and mature way to be. So why dare to love? Why dare to follow our dreams if failure is an option? Because of courage, Peterson answers. Because — at our best — we are courageous people desperately wanting to impact the world in a way no one else can. So we don’t take our dreams to the grave.

The conclusion of any period of time brings reflection. At the end of the second millenium, newscasters reviewed the achievements of the last thousand years. Every New Year’s Eve, we reminisce and resolve for the year to come. Now, at the end of four years in Waltham, it bears mentioning how far we’ve come. Consider how much we’ve grown intellectually, socially and spiritually, perhaps.

It might not feel this way, but we’re ready. We’re ready to solve issues in healthcare and law, business and education. The Brandeis campus might not have the best architectural integrity, but it sure was a hell of a good education.

Now, an aside. In the year 2000, Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam wrote a book called “Bowling Alone.” He discusses the decline of social interaction in the United States since the 1950s. Less people are involved in civic organizations, adult sports teams and all sorts of other groups.

From once bowling in leagues, Americans are largely now bowling alone.

“The loneliness epidemic” is what Psychology Today called this phenomenon in a recent article. Here are some statistics from a recent survey: Over 46 percent of Americans asked said they feel alone sometimes or always. 43 percent feel isolated from others. And only 53 percent of people said that they have meaningful in-person interactions regularly.

Loneliness rates have doubled since the 1980s, and the mental and physical health results of this are disastrous.

Why are people feeling alone? Robert Putnam blames television and the internet. Many people have families, he says, and many of them have friends, too. But not everyone in this country has community. Sure, there are pockets of certain ethnic and religious groups that stick together — Hindus and Jews, for instance — but many Americans, many Westerners don’t have that anymore.

We’ve pluralized and diversified, studied abroad and broadened horizons. Many of us have grown tall while neglecting to grow deep. Many Americans don’t feel like essential parts of a community anymore — don’t experience the lively caring dynamic thing that is a social fabric.

But at Brandeis we’ve had that. At Brandeis we’ve all been part of this radiant web of light that’s connected us all. We’ve banded together, participating in Shabbat or complaining about Sodexo, tripping down the Rabb steps or falling asleep one too many times in the dungeon.

Whatever it is, we’ve been part of this really special community — and what I want to encourage everyone to do is remember that, and remember that this is just the beginning.

Several weeks ago, like many of you all, I attended a seder with my cousins in New York. Some time in, we read about the four children — the wise, the wicked, the simple and the one who doesn’t know how to ask. Naturally, my mischievous younger brother Ben was chosen to talk about the wicked child.

He asked, “What is this worship to you?” This is what the wicked child says. I thought for a minute — what’s so wrong with that? What makes this son wicked? He’s not mean, or arrogant, or walking around flaunting a big ego. What is he doing wrong?

“He excludes himself from the collective and thus denies the Jewish faith,” the Haggadah says. “If he had been there in the Exodus, he would not have been saved.”

So his sin is regarding himself as outside the community! This is how important is to be part of the collective. Even if you feel different than most people, there’s a spot for you. There’s a spot for everyone, and there is not only a space but a certain responsibility that we each have to bring others in. It is up to us to be part of our communities, to make them vibrant, caring and amazing. The responsibility falls upon us.

I encourage us to remain involved in this special, exciting community — to not take it for granted by really indulging in it as much as we can. We may be leaving Brandeis, but this is just the beginning.

And, one last thing: Fronti Nulla Fides. In the words of Amor Towles, “place no trust in appearances.” How often it is the case that we are deceived by appearances. May we all have the wisdom to discern facade from depth and pursue what’s truly meaningful

If you’ve made it this far, I thank you for reading my corny commencement address. Cheers to living into the answers and, of course, congratulations to the Class of 2019.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.