Environmental deregulation is harmful to all

Modern-day voters may have trouble believing that a Republican president signed the suite of environmental regulations that we rely on today into law. “Clean air, clean water, open spaces. These should be the birthright of every American. If we act now, they can be,” declared President Richard Nixon in his January 1970 State of the Union address. And act he did, by approving and funding the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. President Nixon approved the implementation of more stringent emissions standards with the Clean Air Act that same year, as well as regulations concerning watershed pollution with the Clean Water Act in 1972. Finally, among other bills, he signed the Endangered Species Act in 1973, which has since protected not only threatened animals but also the habitats they occupy.

These pieces of legislation are back in the news this week as the Trump administration puts pressure on the EPA to strip the Clean Water Act of considerable power and efficacy. EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler introduced a comprehensively revised version of the “Waters of the United States” rule, limiting its scope, according to a March 20 CNN report. The amended rule redefines the concept of the “Waters of the United States” to classify fewer small waterways as under federal regulation, according to a March 1 NPR article. This has the effect of limiting the Clean Water Act standards’ applicability and thereby rolling back stream and watershed protection. The proposed rule is open to public commentary until April 15, though what the EPA will do to address feedback is unclear.

The previous, more expansive definition of “Waters of the United States” was approved by the Obama administration in 2015. Brandeis Legal Studies department students may be familiar with it from the case of John Rapanos, a real estate developer who challenged the federal government’s jurisdiction to protect small waterways on his property. The outcome of the case was unclear, and so the authors of the 2015 Clean Water rule sought to clarify the definition of, and in turn broadly protect, U.S. waterways. Since the EPA repealed the 2015 rule last August, the documents detailing it have been deleted from the EPA and the House of Representatives’ websites.

According to Ron Klataske, a rancher and head of the Kansas Audubon Society, who gave comment for the NPR story, the redefinition represents “the greatest rollback of conservation and protection of ecological resources that has occurred ever.” In contrast, farmers and large agribusinesses are mostly enthusiastic about the proposal. Administrators and legislators often struggle to strike a balance between environmental protection and economic concerns. However, it is curious that an EPA Administrator who has cited clean-water access as his number-one concern would move to decrease regulations on water pollution. (In his opinion, climate change is still 50-75 years out, but that is a topic for another column.)

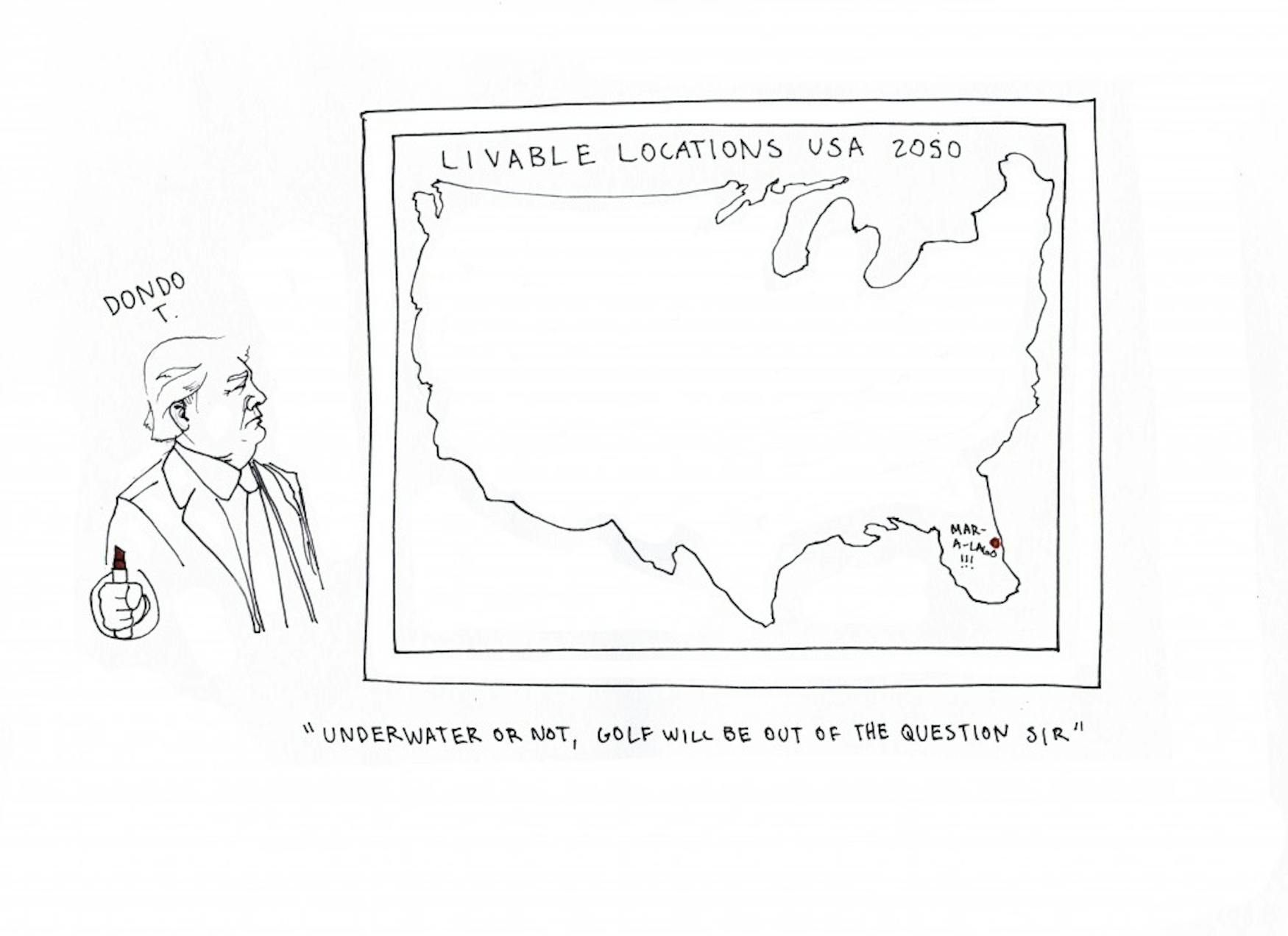

Two years ago, I wrote about the Republican-controlled Congress and President Donald Trump’s use of the Congressional Review Act and the bicameral Republican majority to repeal Obama-era environmental legislation. The news that the Trump administration is once again trying to dismantle decades of environmental reforms is unsurprising. This rollback is “necessary,” apparently, in order to reinstate a form of laissez-faire capitalism that creates far fewer winners than losers. Not only is economic (especially environmental) deregulation backwards, the administration’s moves are proving unlawful. According to a March 19 Washington Post article, federal courts have ruled against the administration at least 63 times. The administration has not acted within the letter or the spirit of the law when designing environmental policy.

In different ways, the 116th Congress and the American people have affirmed that environmental deregulation is not what they want. Both houses of Congress voted to expand the Wilderness Act, according to a Feb 26 National Geographic article. This move was significant because it affirmed a commitment to the conservation of specific natural areas. “Communities across the country have never stopped caring about public lands,” applauded a conservationist in the article. However, wilderness preservation alone is not enough to solve environmental issues. As noted environmental historian William Cronon argued in his 1995 essay, “The Trouble With Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” viewing environmental conservation solely as a matter protecting pristine wilderness ignores the fact that nature is everywhere. Conservationists view National Parks, monuments and other protected recreational areas as instrumental to fostering a successful environmental movement because their beauty inspires people’s enthusiasm for nature and thus, conservation. However, according to Cronon, they also cause Americans to view nature as distinct from everyday life; a place only for recreation and not for work or day-to-day life. This is despite the fact that bacteria and pollution pay these boundaries no mind as they travel the earth. While it is important to protect special areas, treating them as separate from the places we live and work lessens our awareness of the environment’s role in our everyday lives.

The Clean Air and Clean Water Acts are essential to the protection of this country’s environment because they apply everywhere and not just in a few designated areas. They regulate pollution that has far-reaching effects beyond the immediate area of emission. Gutting them while ramping up protections for wilderness areas further removes us from nature and tells us that the quality of everyday life is not important.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.