College admissions isn't meritocratic, but it still matters

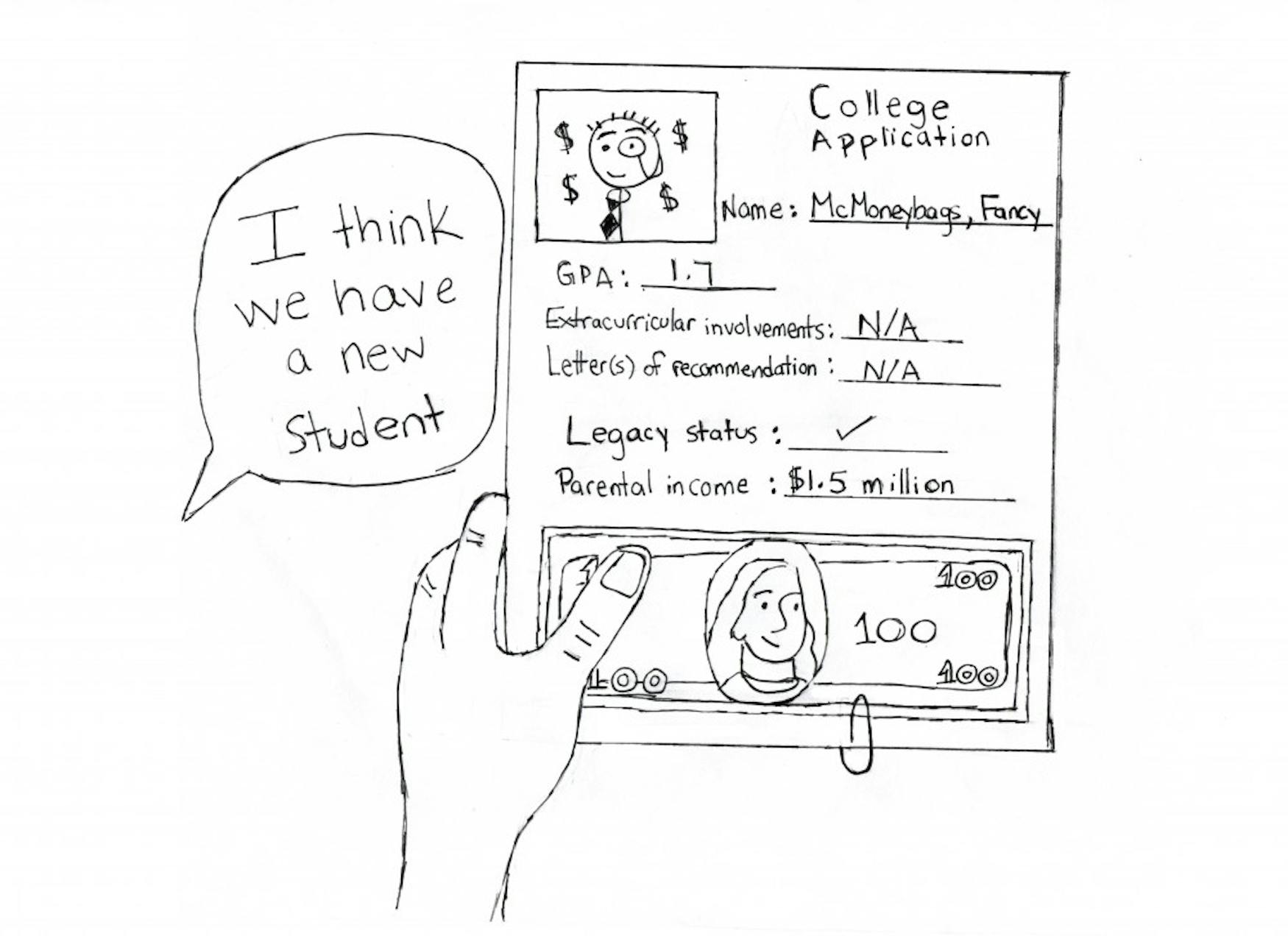

Here are some interesting statistics: according to NPR, the regular admission rate to Harvard University is 5.9 percent. If one of your parents went to Harvard, it’s nearly 34 percent. In 2017, one-third of incoming class members were children of alumni.

I don’t mean to pick on Harvard. This is merely one example of legacy admissions, the above-board, totally legal process of giving an admissions boost to children of alumni. Almost half of private universities in the United States consider legacy a factor in their admissions decisions, including Brandeis, and though it is far less common, some public universities also consider it.

Here’s something else that’s worthy of your attention: Jared Kushner, President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, was not a remarkable student in high school. In Daniel Golden’s 2006 book “The Price of Admission,” an official at his high school said: “There was no way anybody in the administrative office of the school thought he would on the merits get into Harvard. His GPA did not warrant it, his SAT scores did not warrant it. We thought for sure, there was no way this was going to happen. Then, lo and behold, Jared was accepted. It was a little bit disappointing because there were at the time other kids we thought should really get in on the merits, and they did not.”

Kushner was not the child of alumni; he was something much better. His father donated $2.5 million to Harvard, thereby securing his son a spot. Students like the young Kushner are called “development cases,” a euphemism for institutionalized bribery benefitting the mega-rich. Again, it is not a practice unique to Harvard, and it is practiced at many elite universities. While exact numbers are hard to come by for most colleges, Dartmouth reported in 2014 that donations were a factor in 4 to 5 percent of applicants’ acceptances, on top of legacy admits. In the early 2000s, Duke reported that about 100 students were development cases.

This is not an article about abolishing legacy admissions or development cases. The argument for that is pretty straightforward and would take about four sentences: in an ideal world, personal accomplishments would matter more than your lineage or your family wealth. This is an article about how, despite all the evidence to the contrary, many Americans still seem to view elite college admissions as a meritocratic process, and our society as a whole still places a huge emphasis on university prestige.

Last week, a scandal broke: the Federal Bureau of Investigation charged dozens of wealthy parents for falsifying applications and bribing admissions officials in order to get their children into elite universities, both private and public. The incident received a huge amount of news coverage, and widespread anger was directed at those involved.

Don’t get me wrong, this sort of corruption is mind-bogglingly unethical and pathetic. But the parents facing criminal charges are not facing prosecution because they used their wealth to rig the system in favor of their unremarkable children; rather, they went about rigging the system in an unusually direct way. Had people like Felicity Huffman provided funds to construct a new building on campus rather than resorting to bribing admissions officials, no one would’ve minded.

The shock over the FBI bust is important: it reveals that most Americans are still fundamentally unaware that the college admissions system is not meritocratic. It’s not about top colleges simply choosing the best and brightest of America’s youth. It’s a complex formula balancing merit with other factors: alumni donations, legacy, getting the right number of tennis stars and oboe players and, of course, celebrity status. If this is the system we have, we’d be better off openly acknowledging it, rather than continuing to pretend that the college you attend is some kind of objective statement about your accomplishments.

However, simply throwing your hands up and accepting that the college admissions system is unmeritocratic is a hard pill to swallow, and for good reason. Here’s another fact: every single Supreme Court Justice attended either Harvard or Yale Law School. Of the nine, only one attended a non Ivy League undergraduate school, and none attended a public university . Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren remains the only tenured Harvard law professor to attend an American public law school .Try googling the educational histories of prominent judges, academics, investment bankers, journalists, politicians — even late-night comedy writers! You’ll find prestigious universities vastly overrepresented, far past the point where it could be argued that it is a natural result of meritocracy.

This is not just relevant to aspiring Supreme Court justices or Wall Street billionaires. In the New York Times’ article “Six Myths About Choosing a College Major,” reporters analyzed data and came to the conclusion that when it comes to earning potential, college choice matters more than major choice: “the better the college, the better the professional network opportunities, through alumni, parents of classmates and eventually classmates themselves.”

This is the underlying issue: if university prestige weren’t such a potent agent of class division, perhaps the obvious injustices in the college admissions process — not to mention the many other barriers after admission, like paying for college — wouldn’t bother us so much. I don’t mean to suggest that people from less elite universities can’t be wildly successful, or that going to an elite school is a guarantee of a great career. Life is much more complicated than that. But college choice is far from inconsequential. The benefits of attending an elite university are particularly pronounced for low-income students. When the Jared Kushners of the world enroll at these universities, they are taking a spot away from a more promising student for whom an elite education could have been life-changing. The stakes are high.

In the wake of the FBI scandal, some have questioned the principles behind legacy and development practices, as well as other ways that money helps in the college admissions game, such as those raised by the New York Times’ article on the college consultant business. But far fewer have approached the question from this angle: what if, in addition to trying to make the system fairer, we tried to make the system matter less? Unfortunately, dismantling America’s obsession with symbols of prestige will take much more than an FBI bust.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.