Profs discuss GDP, deficit and national growth in U.S.

They examined the roles of interest rates, federal borrowing, fiscal policy and more.

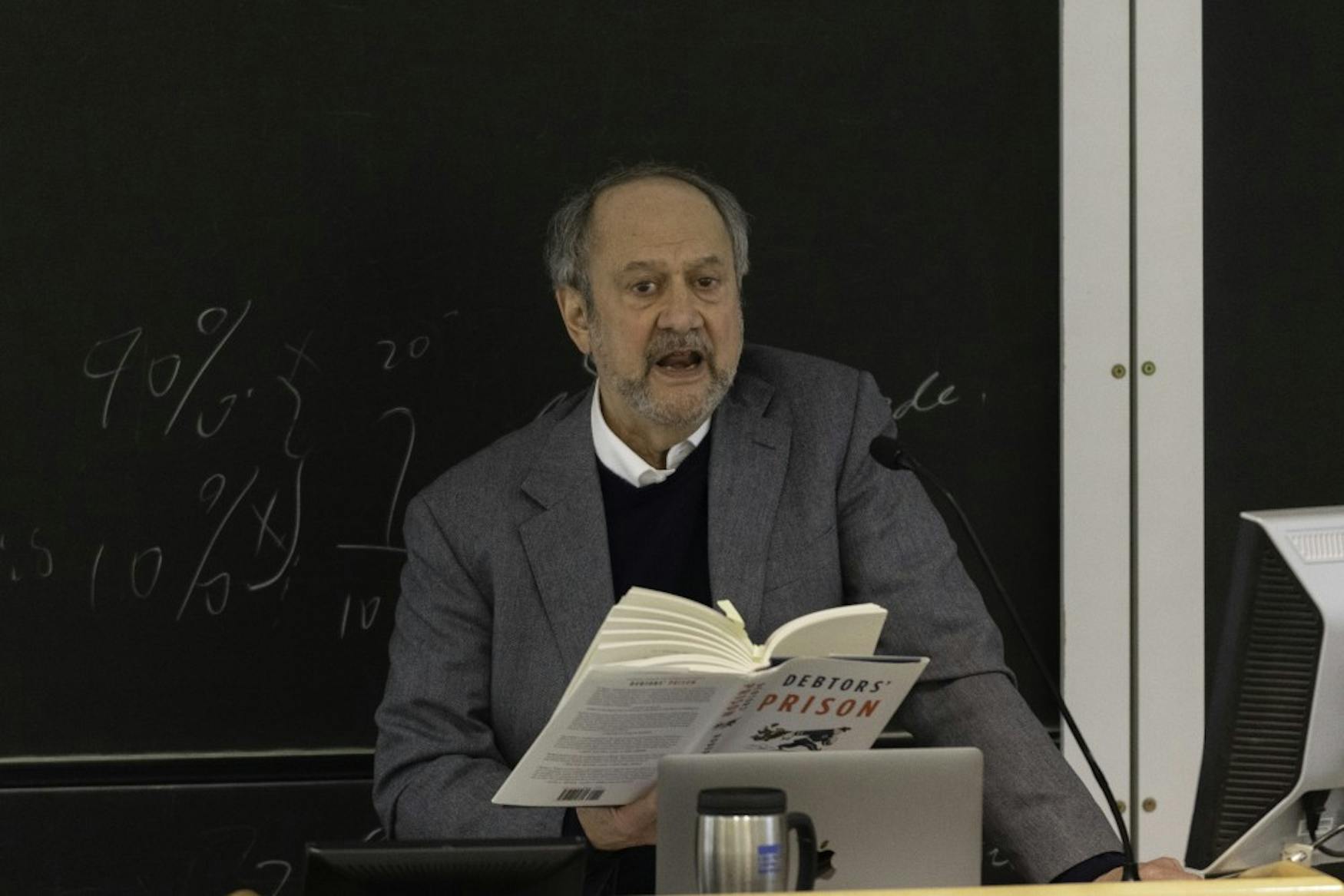

To improve the state of the national economy, the government must intervene to stop the increase of the national debt, Prof. Robert Tannenwald (Heller) and Prof. Robert Kuttner (Heller) said in a panel on Wednesday, with a Q&A following the dialogue. During their panel, the two discussed the current national debt issue and proposed solutions to lower the budget deficit.

Tannenwald began by debunking common misconceptions of the debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio’s role in the national deficit, asserting that it is essential for governments to establish the role of the national debt and deficit in national productivity. The public is “alarmed” by the “major crisis” posed by the federal debt to the GDP, Tannenwald said. This is due to to the misconception that the increase in federal borrowing causes the federal interest rate to increase, which crowds out private investments from households. Crowding out is the depression or elimination of private sector spending caused by a rise in public sector spending, which accelerates inflation despite the government’s attempt to curb it.

Tannenwald finds this reasoning to be “fundamentally flawed,” as it portrays the debt-GDP ratio as a “cause” of the national deficit rather than a “symptom.” Contending that government intervention should have the goal of reframing “fiscal and monetary policy,” Tannenwald stated that the overarching objectives for governments should be raising “living standards for all Americans” and “redistribut[ing] income and wealth.” In the past three years, the government’s taxation policy has been favoring wealthy individuals at the expense of people in lower income brackets, according to an Apr. 15, 2016 Gallup News poll. Tannenwald also proposed re-regulating federal borrowing to “stop financial leads from making private profits” while ensuring fair compensation for workers. In the meantime, he would “engage in critical public investments” to stabilize the national economy.

Tannenwald acknowledged that the public often associates debt-GDP ratio with financial decline, and challenged the misconception by emphasizing that being fiscally responsible in the long run without exceeding the debt-to-GDP ratio threshold will stabilize the economy even with outstanding debt. At the end of World War II, the debt-GDP ratio was 124 percent, but the Federal Reserve sold bonds that “paid real dividends” and boosted real economic production by 50 percent, according to Tannenwald. According to Congressional Budget Office, the current ratio is 105.4 percent, which is “nowhere near the [90 percent] threshold.” To pay for necessities and public investments, the “[debt-to-GDP] ratio is still prudent if we spend it on the right thing[sic],” Tannenwald said.

Kuttner, who researches globalization and democracy politics, agreed with this remark. “In order to restore confidence in government, we, Democrats, have to be the fiscal grown-ups in the room,” he said. During a financial recession, the government does not normally take the impact on the ordinary household into account because of its authority to spend “countercyclically,” which is the continuation of government spending despite financial downturns, Kuttner said. During his 2010 State of the Union address, then-President Barack Obama urged the government to consider the implications of the national debt on the ordinary household’s well-being. Obama stated that “families across the country are tucking their belts to make tough [financial] decisions, but the federal government should do the same.”

During the Q&A, students asked the professors questions about how government intervention could aid in increasing public investment and account for the societal effects of the deficit. One student was fascinated by how the application of monetary theory contributes to the historical presence of U.S. productivity growth. Tannenwald responded by explaining the recent tax cuts instituted by President Donald Trump, which resulted in the overcompensation of Executive Officers and the undercompensation of unskilled laborers. Two months after the ratification of tax legislation, the Tax Policy Center’s Analysis reported that the top 1 percent earners should expect to receive an average cut of $51,000, while the lowest 20 percent of earners could only see a reduction of $60 this year. Kuttner echoed Tannenwald’s point, expressing his support for public investment. Despite being subject to the antitrust commission outlined by the Federal Trade Commission, some companies undergoing monopoly buyouts adhere to the practices of the private sector “simply because they don’t know cheaper ways of investment,” Tannenwald explained. In the private sector, the buyouts do not contribute to the GDP. Thus, he expressed the need of accounting for public sector in “real investment.”

When asked of his opinion on a wealth tax proposed by Democratic presidential nominees, Kuttner raised the problem of the possession of property taxes on real estate. In theory, the property tax is a federal tax but is levied at the local level, which diminishes public confidence in the government’s ability to tax. While levying taxes on wealthy individuals could decrease the wealth gap, this would create a potentially risky situation for those in the next-lowest income bracket. “We need leadership that can narrate [a] case for change,” Kuttner emphasized.

To conclude the panel, Kuttner discussed the current education funding using local property taxation, which subjects to a very large school-aid program at state level and, as he, “radically, fiscally equalizing.” “More school funding should be provided,” Kuttner said, “but [the current funding] now is on the right track.”

Despite analysing the national debt through different lenses, the duo recommended policymakers be held accountable to be fiscally responsible, increase public investment and be prudent with the national debt to ensure long-term productivity.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.