Superbowl ads are emotionally manipulative

The Super Bowl is a celebration of all things American: snack foods, big crowds, boundless passion, nefariously concealed concussion scandals and colossal amounts of money. Perhaps its most American feature is the widespread concept of “watching for the ads.” Across this great nation of ours, countless individuals — myself included — passively watch a sports game they’re not terribly invested in, in order to enjoy being marketed to.

As a person who eagerly avoids ads in all other contexts, it’s hard to articulate the appeal of Super Bowl commercials — but I’ll try. Due to the vast amounts of money invested in creating them, they’re cinematically produced, usually well-written and generally a step above the everyday stream of aggressive marketing we all experience. If regular ads are bologna, Super Bowl ads are steak tartare. The price of these time slots makes it fascinating to watch companies optimize their few seconds of airtime. They’re also a source for Monday-morning small talk, which is especially useful if you’re trying to avoid an in-depth conversation about the actual game.

The best Super Bowl ads are the funny ones, especially those that focus so heavily on humor that they barely mention their product. I also have a soft spot for the weird ads, although many people would disagree with me; according to USA Today’s survey, Burger King’s ‘Andy-Warhol-eats-a-burger’ approach was the most hated ad this cycle. I would beg to differ with this consensus. Warhol might not be to everyone’s taste, but the worst Superbowl ads are the manipulative ones.

Here’s the thing about the emotionally manipulative Superbowl ads: they never start out by telling you what they’re selling. First it’s the cinematic shot of the soldier returning home, or the abused kittens, or the mother holding her infant for the first time; you get the picture. The Bob Dylan song plays; flags are waved by cute children. Then, at the very end: apparently, this is a car ad. What does a puppy kissing a horse have to do with buying a car? You’re not sure, but it’s hard to criticize - after all, who wants to be the guy that makes some cynical remark about puppies? All that remains is the vague connection forged in millions of minds: puppies, horses ... and Ford Explorers.

While manipulative, irrational advertising is unusually blatant during the Superbowl, it is also present in everyday marketing. In fact, it’s become so common that it’s easy to stop noticing it. Will using a certain awful-smelling deodorant really attract crowds of voluptuous blonde models? Will purchasing this specific brand of watery beer get you invited to giant parties? Will this particular car send you on grand adventures along rocky coasts? It’s easy to laugh at these common examples, but the fact that this type of illogical connection-forging is so common among marketers is evidence that it works well enough to justify production costs.

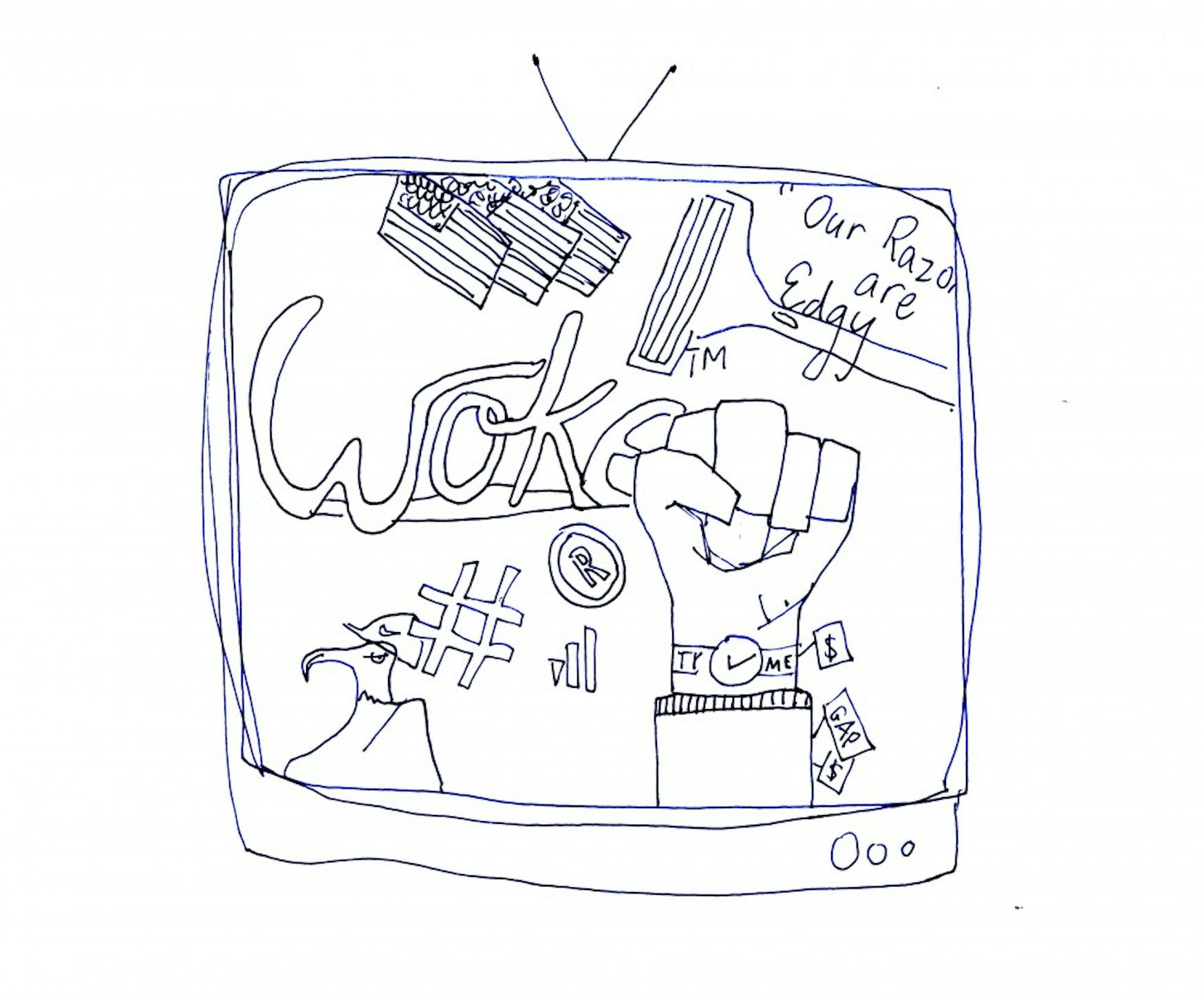

Emotionally manipulative advertising extends to social movements, too. Occasionally this can backfire, as in the case of the remarkably stupid Pepsi ad that suggested soda could heal racial divisions and solve police brutality. More often though, the gamble pays off. Observe the recent Gillette ad that capitalized on the “#MeToo” movement and the public’s growing awareness of toxic masculinity. Just as Gillette desired, their brand got an incredible amount of press coverage in the ensuing partisan debate. Less attention was paid to the fact that shifting gender norms are not terribly relevant to the quality of Gillette razors versus competing brands’.

While this practice of co-opting social movements seems to have gained popularity in the last few years, it’s nothing new. For a long time, cigarette sales were lower among women due to smoking’s masculine reputation. To remedy this, Virginia Slims’ successful 1968 ad campaign adopted women’s liberation slogans to make smoking seem cool and feminist, according to the Center for Disease Control.

Imagine, for a moment, something crazy: a world where advertising is fact-based, rather than an exercise in psychological tinkering. A car ad tells you their new model’s gas mileage and price versus competitor’s cars; a deodorant ad explains why their particular pine scent is better than the hundreds of other options.

Of course, the obvious response to this is that if straight forward marketing worked better, companies would already be doing it; the only reason they use these tactics is because flag waving makes more money than honesty does. So perhaps it’s our responsibility to be aware of our often-illogical motivations behind brand preferences. If advertising’s power to shape consumer’s thinking faded, branded products could be seen less like magical life-improvers, and more like ordinary, mass-produced objects.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.