50 years of AAAS: remembering a resistance

The fight for an African and African American Studies department

The Department of African and African American Studies (AAAS), established on April 24, 1969, is celebrating its 50th anniversary this week, but the history of Black students and their influence at Brandeis existed long before then. The legacy of Black intellectuals like Ralph Bunche — scholar, eventual Nobel Peace Prize recipient and Brandeis’ first convocation speaker — and Brandeis’ first Black graduate Herman Hemingway ’53, founder of the University’s NAACP chapter, helped Brandeis establish its reputation as an institution of social change.

Despite hosting several addresses delivered by civil rights figures like Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. during the mid-1960s, there were very few Black students actually attending the University. According to Angela Davis ‘65, the “physical and spiritual isolation were mutually reinforcing.”

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968 was a turning point for America, Brandeis included. To make Brandeis a truly welcoming place for those of African descent, the Afro-American Society issued various proposals to then-President Abram Sachar. These proposals culminated in the creation of the Transitional Year Program (now known as the Myra Kraft Transitional Year Program) and 10 Martin Luther King Jr. scholarships, as well as an increase in financial aid for Black students. As a result of these changes, the number of Black students enrolled in the fall of 1968 more than doubled that of fall 1967, and Pauli Murray became the first female African-American professor hired at Brandeis in 1968. On December 11, 1968, the faculty approved the African and Afro-American concentration.

On December 18, 1968, a white student allegedly shot a Black TYP student with a BB gun, illustrating the amount of racial tension on campus. The administration refused to expel the white student unless a formal trial was held, but no one pressed charges.

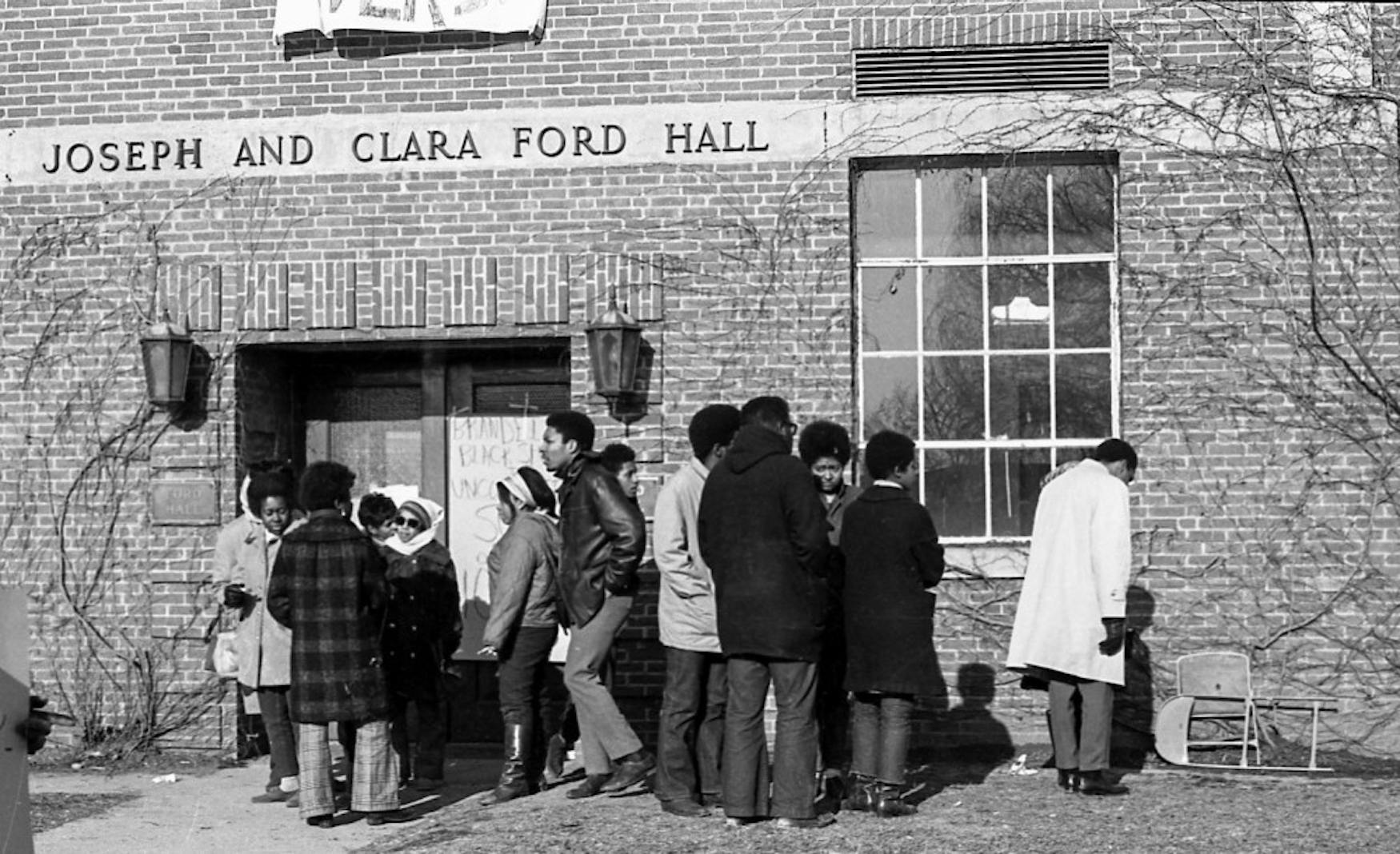

While Brandeis has always considered itself an institution open to people of all backgrounds, ethnicities and races, the lack of an AAAS department was seen as a disservice to Black students. On January 8, 1969, more than 50 Black and Latinx students occupied Ford and Syderman Halls; the former was the main academic building where the University switchboard was located.

Ricardo Millet ’68, the Ridgewood residence counselor, and Roy DeBerry ’70, president of the Brandeis Afro-American society, read a prepared statement that presented a list of 10 demands to the University. They called for complete amnesty for the students involved in the occupation and claimed that their demands were non-negotiable. Their most prominent demand was for the creation of an African Studies department. While the already-existing African and Afro-American concentration could have been shut down at the University’s discretion, a full-fledged department would have the ability to hire its own faculty and determine its own curriculum. Other demands included an increase in the recruitment of Black students, the addition of Black professors to various departments, the establishment of an Afro-American center and the expulsion of the white student who had allegedly assaulted a Black student. The next day, the occupying students renamed Ford and Syderman Halls as the Malcolm X University; however, Ford Hall is still known by its original name.

The evening of the protest, some of the students involved in the occupation held a meeting in Mailman House. Phyllis Raynor ’69, a representative of the Afro-American Society, presented the demands to other, primarily white students, but let them decide how they would respond. A Jan. 10 issue of the Justice describes the “white Brandeis community” as reacting with “a stunning array of attitudes: sympathy, fear, hostility, recalcitrance, speculation, and, above all, confusion.”

Many white students did support the movement. On January 9, 400 students met in Gerstenzang 123 to draft a petition. The ultimate consensus was that there should be no use of police or force of any kind, no more buildings should be occupied, and that all channels of communication should be kept open.That day, there was also a sit-in at the Bernstein-Marcus Administration Building. On January 10, 22 white students engaged in a hunger strike.

However, there was also opposition to the occupation. President Morris Abram issued a statement condemning the Black students’ actions, noting how they never formally presented their demands to the administration. After hearing this statement, faculty approved a resolution by a vote of 153 to 18 calling for the students to leave the

building.

The occupation ended on January 18. While no substantive agreements regarding the 10 demands were made, President Abram stated that “every legitimate demand would be met in good faith.” Most students were granted complete amnesty, except for a few members who stayed in the building after the others had left. On April 24, faculty approved the creation of the African and Afro-American Department. Ronald Walters, a political scientist and specialist in African studies and international affairs, was announced as the chair of the AAAS Department on April 30. In the fall of 1970, the Department offered its first 20 courses.

However, the department has faced struggles. After its creation, the University provided minimal funding, and some faculty believed the subject of African and Afro-American studies wasn’t significant enough to warrant its own department. Despite this, the department persisted. Wellington Nyangoni, a renowned scholar of African politics and the first Black professor to receive tenure at Brandeis, was appointed as the chair of the department in 1976. The department has continually been a center for political activism, especially regarding the anti-apartheid movement and divestment.

But even as recently as 2008, during the economic recession, a committee looking to optimize the University’s finances suggested combining the AAAS, American Studies, and Classics Departments. This suggestion was met with immediate protest by University members and was formally opposed by faculty and the Student Union Senate. The resistance was successful, and the AAAS Department remains.

Following this incident, various improvements were made to the Department. There were incremental increases to the department’s budget. The Department has also bolstered its on-campus presence with better programming and more collaborations across the University.

The Department’s legacy as a focus for racial justice and change isn’t just something of the past. In 2015, the AAAS Department was largely involved in the occupation of the Bernstein-Marcus Administration center. As a response to the Black Lives Matter movement, students made 13 demands, including the hiring of more black faculty, an increase in the minimum wage for Brandeis employees, and diversity and inclusion training. The protest was named #FordHall2015 in honor of the movement for racial justice at Brandeis in 1969.

As a result of this protest, the University has hired faculty such as Mark Brimhall-Vargas, the first Chief Diversity Officer, and Allyson Livingstone, the first director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion education, training, and development.

This Friday and Saturday, the AAAS department is hosting several campus-wide events as a commemoration to their 50th anniversary.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.