Having more options does not lead to happiness in every situation

Apparently, the United States is experiencing a “sex recession.” This month’s cover story for The Atlantic documents how and why Americans are having less sex than ever before, and seeks to answer how this phenomenon could be possible. In our liberal era, with access to potential sex partners easier than ever thanks to apps like Tinder, with taboos around sexual promiscuity falling and access to pregnancy and STD-preventing devices rising, how could it be that we’re actually spending less time in the bedroom?

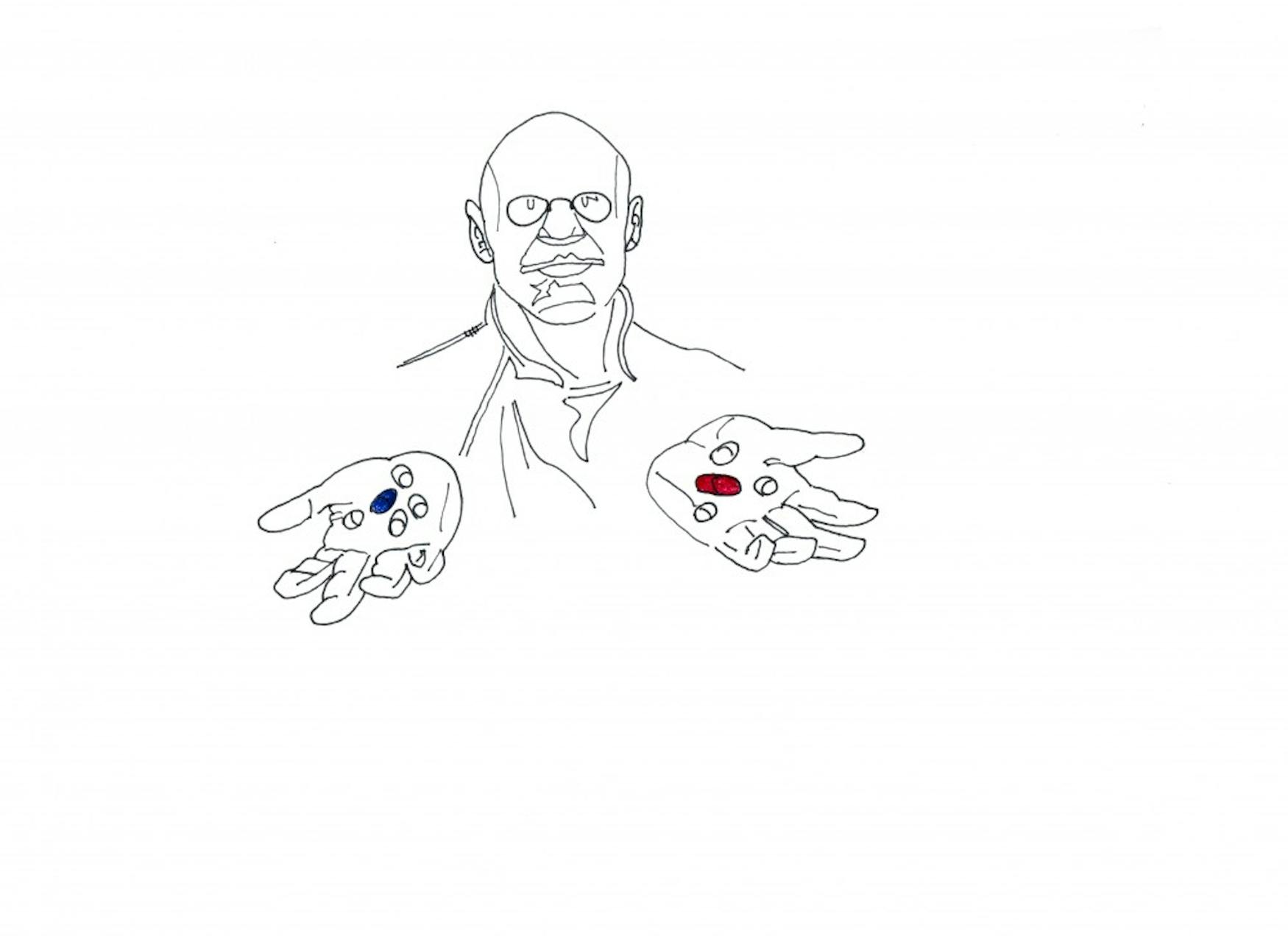

The article cites many potential answers, from hookup culture to surging anxiety rates. What I want to talk about is one factor in particular that I believe is one of the most consequential: choice overload. There are people who are so daunted by all the options, the author writes, that “they don’t make it off the couch.” In her interviews, “some people used the term paradox of choice; others referred to option paralysis (a term popularized by Black Mirror); still others invoked FOBO (“fear of a better option”).”

If technology has ushered anything into our lives, it’s more options — of things to buy, friends to text, partners to love. A recent Vox article discusses how this so-called option paralysis has driven not only indecision, but flakiness. The author writes, “None of my closest friendships were forged solely because we had so much in common or it was convenient. It was because we prioritized each other. When we had options — and there are always, always options — we chose each other more often than we didn’t.”

The notion of jettisoning constraints is appealing in America because it is part and parcel of freedom, and arguably nothing is more American than the pursuit of freedom. In a sense, commitments inhibit freedom. They prevent us from choosing other options. And what happens when we doubt that choice? We “flake” and move on. Is this true freedom, moving from one option to another? Or could it be that freedom actually does not entail navigating the endless varieties of cereal in the supermarket, or everlasting pages of every Amazon search?

Famously, there are two conceptions of freedom: positive and negative. The former constitutes a “freedom to” do what one pleases, and former is a “freedom from” external restraints or obligations. What our abundance of choices in America presents today is certainly the former: We can choose whatever we like. This, in theory, should prompt us to be more effective in choosing the option that best satisfies our needs and wants.

But of course, this is not always the case. People become overwhelmed by too many options. Until the 1990s, many psychologists held the view that more choice is a good thing, and has a positive correlation with happiness: The more choices, the more control and satisfaction people feel they have. In one experiment, scientists brought two sets of toddlers into a room. One set was given one toy, another set given several toys. The group given several toys demonstrated higher levels of engagement and satisfaction.

This was common wisdom in the field until Sheena Iyengar of Columbia University discovered that if you offer an exorbitant number of toys to the children — an entire room-full — they become totally disinterested and just stare out the window. What became known as “the paradox of choice” turned out not to not really be a paradox at all, just a bell curve. In short, Iyengar found that “a larger choice set generates more interest; the smaller choice set generates more action,” according to Steven Dubner, host of the Freakonomics Podcast, in a Nov. 28 episode.

Iyengar replicated this type of experiment with Mark Lepper in 2000 in what became the famous “jam study.” In an upscale California supermarket, store employees set up a jam-tasting display with 24 flavors. Anyone who tried a jam received a $1-off coupon to be redeemed on any flavor. On a different day, store customers saw the same stand, except with only six flavors. What the psychologists discovered was that the larger display generated more tastings but the smaller one generated more sales.

These studies and others also show that those people who do make choices among larger sets experience less satisfaction than those who choose from a smaller array of options. A 2006 Harvard Business Review article tried to clarify the thorny relationship we have with choice as follows: “There is diminishing marginal utility in having alternatives; each new option subtracts a little from the feeling of well-being, until the marginal benefits of added choice level off.”

This notion is radical not only because it threatens to undermine our ability to choose life-partners, but also the very viability of the free market. The most fundamental assumption of the free market is that more choice, more trade, more specialization makes everyone better off, if only because each of our unique desires can be satisfied. If choice is, in fact, more accurately represented by a bell curve than a diagonal line up to the right, then customer-facing marketers better take notice.

One grocery store, Trader Joe’s, has a deep understanding of this phenomenon. While the average supermarket contains nearly 35,000 individual items, TJ’s carries only about 3,000 depending on the location. And their heeding of customer psychology has paid off — Trader Joe’s has the highest sales per square foot of retail space in the supermarket industry by an impressive margin. According to Freakonomics’ Nov. 28 podcast on the chain, “A 2012 analysis estimated that Trader Joe’s sells just over $2,000 of groceries per square foot.” Whole Foods’ number totalled about $1,200, and Walmart was at $600.

This extreme idea — keeping options limited in the era of gigantic supermarkets — has been a key ingredient in Trader Joe’s success.

So where do we go from here? We know what the world has to offer. We know that our access is abundant. And yet many of us are still unhappy, primarily, I think, because we don’t know what we want. Should we close our eyes, pick only the items closest to us on the shelf? I don’t think that will leave us feeling any more fulfilled.

What we can do — knowing that unlimited choice actually does limit us — is be mindful of our own brand and know exactly it is that we want. Often, I find that we know more about ourselves than we let on. So let us take the bounty of options we have as an opportunity — not to try what everyone else is trying but to step back momentarily into the silence, forget the 72 varieties of ice-cream and five-million career options, and design exactly the life it is that we want. It might just be the change we never knew we needed.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.