Party like it's 1994, because protectionism is alive and well

In 2012, the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago polled its panel of economics experts, made up of professors from some of the most prestigious universities in the United States, on two questions. The first asked if the productive efficiency and greater choice afforded by free trade outweighed any effects on employment in the long run. The second asked if United States citizens are better off with the North American Free Trade Agreement than they would have been under the prior trade rules with Mexico and Canada. In both cases, the results were undisputed. All but two of the 40 experts agreed that free trade and NAFTA were the better option, and the remaining two answered “unclear.” Not a single one of the experts disagreed.

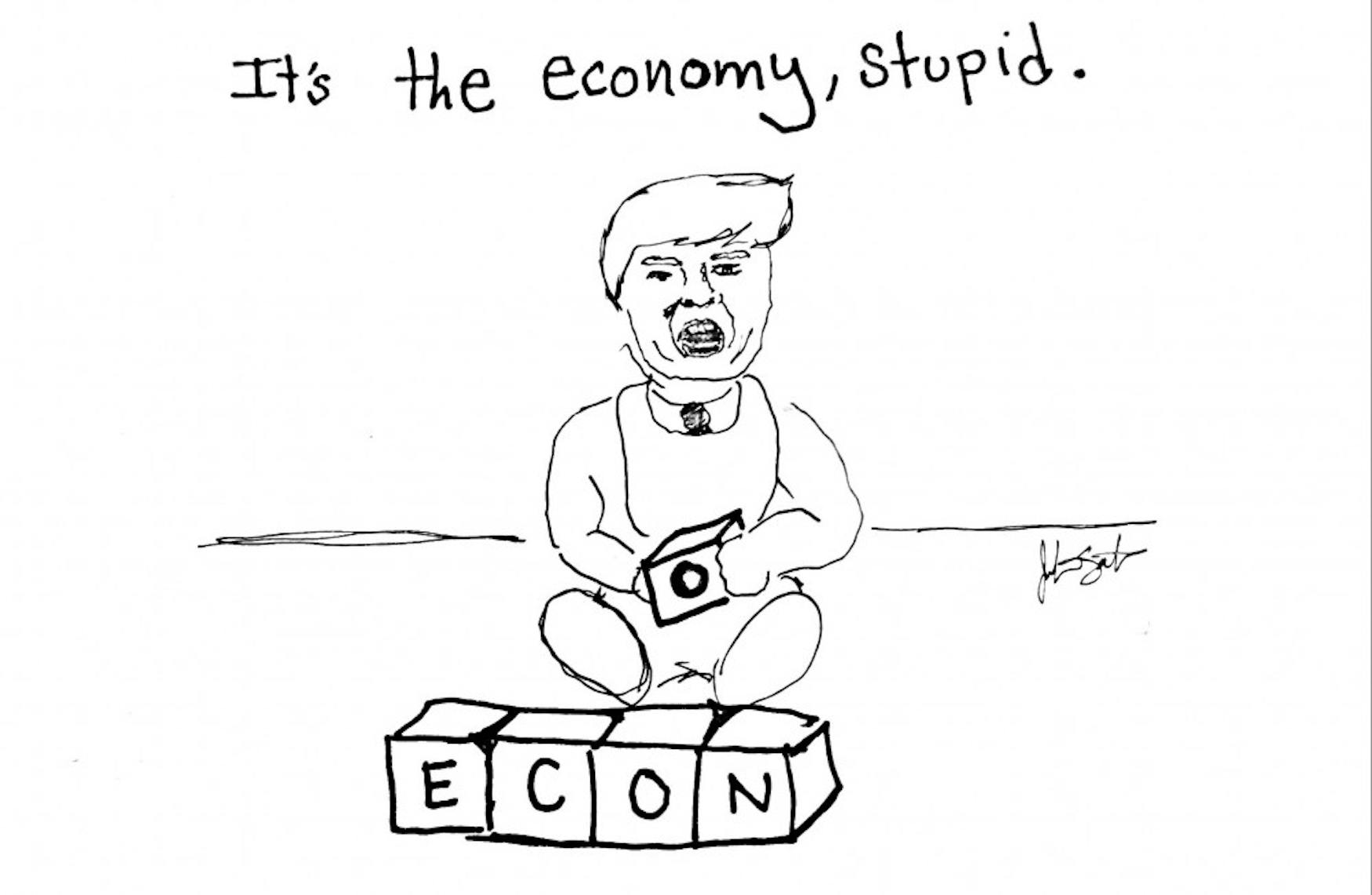

Hearing such sentiments from leading economists is hardly a surprise, given the importance placed on free trade in orthodox neoclassical economics. Among economists, ideas such as the Ricardian notion of comparative advantage carry great sway. The Ricardian notion holds that as resources invested in one activity cannot be used in another, it makes more sense for countries to focus on products it can produce most efficiently. If free trade dominates, the principle of comparative advantage should lead to greater efficiency and enhance global economic welfare. These principles, however, have recently come under fire as the world has seen a rise in protectionism. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi championed the Make in India initiative with the goal of “transforming India into a global design and manufacturing hub,” per the initiative’s website. In Europe, Euroskeptic parties hostile to the European Union’s free trade and freedom of movement have made great strides in recent elections. Here in the U.S., the election of Donald Trump has led to a resurgence in protectionist policy as trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and NAFTA are torn up or renegotiated. Countries around the world now face the specter of tariffs. It is no secret that economic theory and the current realities of trade practice differ greatly, as commerce takes place in imperfect markets shaped by political factors.

In this context, Trump’s determination in shattering decade-old conventions finds its greatest expression in his opposition to China and his hard stance on the imbalances within the U.S.-China relationship. Some policies have been more widely praised than others, such as his instructions to the U.S. Postal Service to levy higher fees on packages from international destinations, a move welcomed by many in e-commerce, from Amazon to small business sellers. In an October 2017 interview with the Atlantic, former Amazon executive Chris McCabe said that after this change, “U.S. Amazon sellers will no longer need to compete so narrowly on price due to the level playing field.” Others have aroused widespread ire from corporate America and many economists, such as his heavy tariffs on many Chinese products. Nevertheless, while there is ample reason to show concern over such a large shift in policy, as with any major change, fully condemning it and its basic principles is folly.

With the rise of globalization and the proliferation of free trade, we have seen immense growth but at the same time immense interdependence. World markets are more than ever joined at the hip, and as companies, supply chains and nations become further integrated, they become more and more fragile. A market decline in America sends Japanese, European and Chinese markets tumbling in reaction. Financial contagion is easily spread, as seen in events such as the 2008 American housing bubble spiraling into a global crisis.

The interwoven nature of global supply chains lends itself to a variety of issues. A May 2012 report from the Senate Armed Services Committee warned of the proliferation of primarily Chinese counterfeit parts in electronics, finding that such vulnerabilities in the supply chain had the risk of threatening the security of key systems. In addition, this issue of security with China extends beyond simple market correlations and interconnectedness. While Bloomberg’s recent Oct. 4 story concerning large scale compromise of American servers manufactured in China has drawn skepticism and denials over its claims from Beijing, China is no stranger to repeated accusations of clandestine activities and espionage from American companies doing business in China.

Perhaps the greatest contention free trade has roused, however, has been in the domain of unemployment. The cost of free trade and globalization has been disproportionately placed on workers in manufacturing industries. The very name “Rust Belt” indicates a sad fate for what was once America’s industrial heartland. When we are increasingly relying on outsourced labor for manufactured goods, there is a reduced demand for American workers, and as such a downward pressure on wages. With labor laws in the U.S. being far more stringent than those of other industrial nations such as China and Bangladesh, wage stagnation and the risk of unemployment grow as it becomes economically preferable to utilize cheaper offshore labor.

Certainly, there are arguments for the trade-offs that outweigh this concern. We all enjoy cheap consumer goods and the shift out of an industrial economy has been met with the rise of new occupations out of our current information-dominated world. This new international environment, however, imposes the demand that one suddenly shift occupations on a dime. For all our attempts at retraining and ameliorating the issue, the fact remains that we cannot ensure any frictionless transition. The difficulty in retraining, say, a 50-year-old factory worker is a hard task in and of itself; to find new employment is even more difficult. The resulting instability creates its own issues in both the economic inefficiency and its social consequences.

Of course, this is not to say that one must always support ailing industries. Forces such as automation will eventually force the matter, regardless of trade policy. Beyond merely addressing the issues of rapidly displaced workers, protectionist policy and the preservation of manufacturing connects deeply with innovation and the technology sector, which has since displaced industry. A July 2009 Harvard Business Review article notes that with the outsourcing of development and manufacturing work, it was not simply low-level tasks shipped overseas. More sophisticated engineering underlying innovation gradually followed, with a similar trend in software as outsourcing of low-level codework to India has led to their own development of more advanced software engineering, and consequently the ability to conduct more complex work. In many industries the processes of production and innovation are intertwined, which means a decline in manufacturing makes higher expertise harder to maintain as it depends on close interaction with manufacturing. Without this, it becomes increasingly difficult to continue to develop new processes and technologies. The comparative advantage the U.S. holds in this area is not something that can be held without effort, nor unchallenged by other countries building up their own industries.

As it stands, the current tariffs and resulting trade conflict has only started, and it is too premature to outright declare any results. The issue remains, however, that the current order is untenable, as evidenced by the strong reactionary movements in the U.S. and around the world. Addressing the myriad of issues in our current globalized and interconnected world cannot merely come from relying on old economic paradigms.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.