The MAGA Bomber is a dreadful sign of things to come

On Wednesday and Thursday, at least nine crudely made pipe bombs were sent to prominent individuals and organizations across the U.S., according to an Oct. 25 New York Times article. The targets span from politicians — former President Barack Obama, former Vice President Joe Biden and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton among them — to actor Robert de Niro, investor George Soros, former CIA director John Brennan and CNN’s New York offices. The connecting factor between these targets was quickly evident: they are all critics of President Donald Trump, and have been repeatedly verbally attacked by him.

The packages were intercepted and no one was harmed. But these incidents sparked debate about the relationship between President Trump’s rhetoric and the likelihood of political violence. While it would be absurd to suggest that Trump has any direct connection to this incident, a leader’s words do not occur in a vacuum. When an event like this occurs — carried out by a single, unstable individual — it is not unreasonable to examine the role that Trump’s consistent encouragement of violence and dehumanization plays in deepening political divisions.

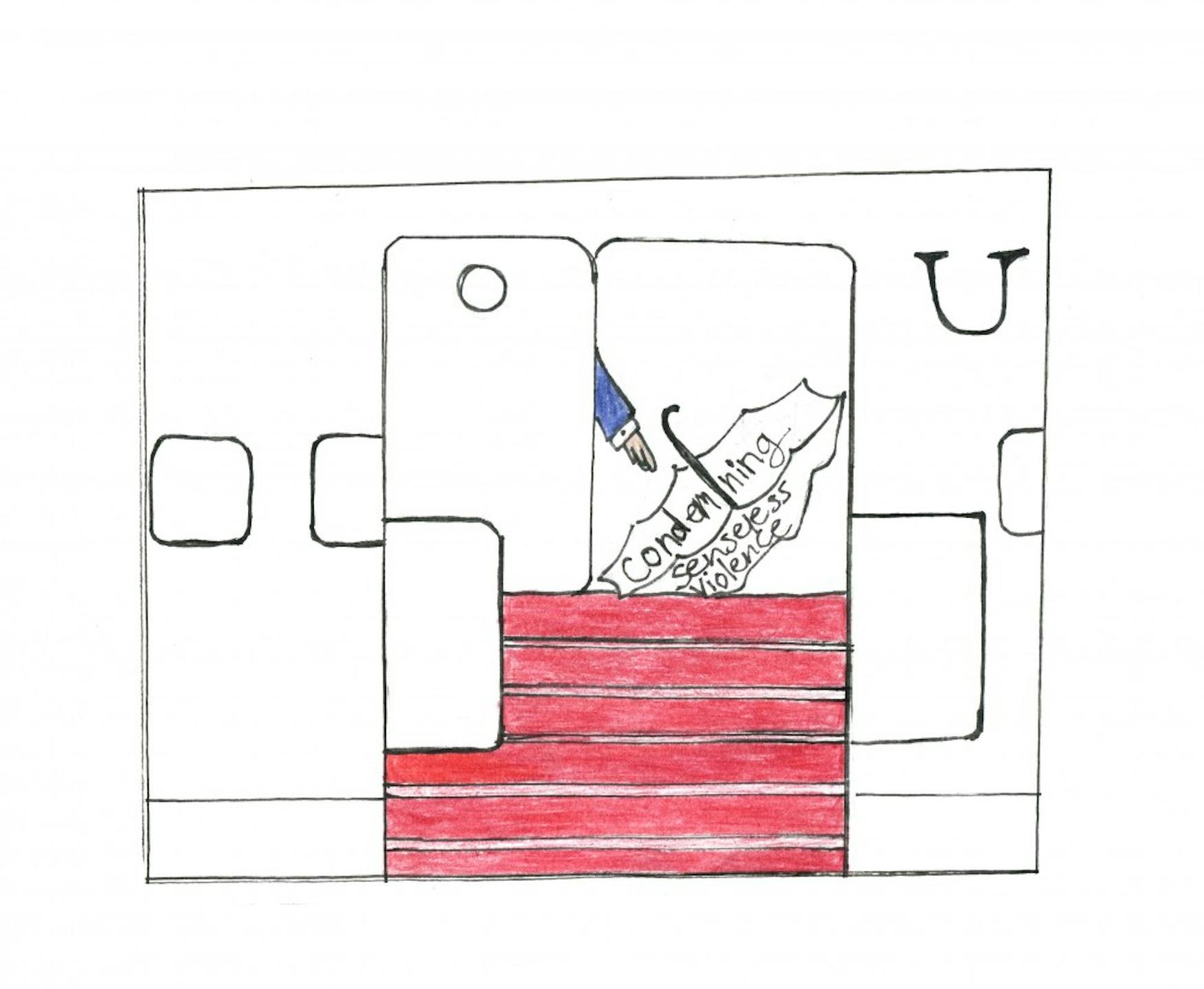

White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders presumably disagrees with all of the above. In a Wednesday night press conference, she called the idea that President Trump’s rhetoric might have encouraged the person responsible “disgraceful,” adding that there’s a difference between “comments made and actions taken,” according to an Oct. 25 PBS article.

Saunders is correct in one respect: there is certainly a difference between comments and actions. But she is mistaken if she believes that “comments made” are irrelevant to the situation. On the contrary, words have power, and the office of the Presidency imbues a person’s words with a particularly great amount of power. After all, one of the roles of a president is to act as a tone-setter for the nation: to guide Americans through times of difficulty, to boost morale and to provide reassurance.

At least, that’s the theoretical ideal. What we have presently is a president who has, over the course of his campaign and his time in office, consistently endorsed violence against his detractors. Consider one sequence of events in early 2016. During a Feb. 1 rally, Trump reacted to protesters by telling attendees to “knock the crap out of them,” telling the crowd “I promise you I will pay for the legal fees.” At another rally later that month, as a protester was being led away, Trump said “I'd like to punch him in the face, I'll tell you.” Similar sentiments continued in subsequent weeks; but when, on March 9, a protester was finally assaulted at a rally, the campaign released a statement stating that they “obviously discourage this kind of behavior and take significant measures to ensure the safety of any and all attendees.”

“Obviously” is not a suitable adjective in that sentence. This overt approval of violence is a hallmark of Trump’s campaigning style. In 2017, Rep. Greg Gianforte (R-Mont.) physically assaulted Guardian reporter Ben Jacobs at a press conference. After Jacobs asked a question, Gianforte slammed him into the ground, punched him and broke Jacobs’ glasses. Just a few days before the interceptions of the pipe bombs, the president praised Gianforte in a Montana rally, saying, “Any guy that can do a body slam, he is my type!”

In another disturbing instance during an August 16 campaign rally, Trump emphasized the important nature of judicial appointments by telling supporters that “If [Clinton] gets to pick her judges, [there’s] nothing you can do, folks.” He then added, “Although the Second Amendment people, maybe there is. I don’t know. But I’ll tell you what, that will be a horrible day.” This apparent call for gun violence against a political opponent led to media usage of an esoteric term also mentioned after the pipe bomb interceptions: stochastic terrorism. Stochastic terrorism is the usage of mass communications to cultivate rage against a person or group in such a way that, as the Times piece put it, “every act and actor is different, and no one knows by whom or where an act will happen — but it’s a good bet that something will.” There is an inherent risk when a person in a position of great power uses that power to focus their supporters’ hatred on another group; the exact risk involved, and the level of moral culpability placed on the inciter, is difficult to quantify — but it is real.

The negative impacts of Trump’s rhetoric go beyond blatant encouragements of violence. When a president repeatedly refers to the media as “the enemy of the people,” calls Mexican immigrants “rapists,” calls women “fat,” “ugly,” “bimbos” and “disgusting animals,” spreads bizarre conspiracy theories about Honduras refugees fleeing violence, and yet says among the ranks of Neo Nazis are “some very fine people,” these words have consequences on what is deemed acceptable and unacceptable in society. Trump fans the flames of fear in order to increase his own political standing, but he has no control over the resulting fires.

Unsurprisingly, the incidents of the past week do not seem to have altered President Trump’s tone. Just one day after CNN offices were evacuated due to the package, the president decided that, rather than promote a message of unity and support, he would take yet another shot at the media through his preferred medium, Twitter. In an Oct. 25 tweet, he wrote: “A very big part of the Anger we see today in our society is caused by the purposely false and inaccurate reporting of the Mainstream Media that I refer to as Fake News. It has gotten so bad and hateful that it is beyond description. Mainstream Media must clean up its act, FAST!”

This behavior is dangerous, it is abnormal, it permanently denigrates the office of the Presidency and it isn’t going away. The battle to restore some semblance of normalcy to American politics will not involve pipe bombs or body slams, but ballots.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.