Univ. fires basketball coach, citing history of racial bias

Looking for a place to sit during a practice session, former Brandeis men’s basketball coach Brian Meehan saw an empty seat next to one of the team’s rookie players, a first-year from Africa.

“Oh, I don’t want to sit next to him because I’ll get Ebola,” Meehan allegedly said, according to an April 5 Deadspin article.

This was one of two incidents in the 2018 season in which Meehan targeted the unnamed player — in the other, according to Deadspin, the coach allegedly threatened: “If you ever talk to me like that again, I’ll ship you back to Africa.”

Nearly 13 years after joining the men’s basketball program, Meehan was terminated earlier this month due to his mistreatment of players. Citing the coach’s discriminatory behavior, University President Ron Liebowitz announced Meehan’s ouster in an email sent to the Brandeis community on April 5, shortly before the Deadspin article was published.

‘We must and can do better.’

Allegations brought to the University last May by three current and former players revealed a pattern of racially biased harassment and discrimination which extended far beyond the aforementioned 2018 incidents; those anecdotes are just a fraction of the larger picture. The complaints were investigated, Liebowitz wrote in the April 5 email, and the University took disciplinary action against Meehan.

Although he would not reveal what these disciplinary actions were for reasons of confidentiality, Liebowitz said in an interview with the Justice and The Brandeis Hoot that options could include written warnings, dismissal or corrective action, such as courses and programs.

The players filed their complaints in May 2017; their case was not resolved until November 2017, after nearly six months of back-and-forth with administrators in the Athletic Department and Office of Human Resources.

Despite the complaints, Meehan continued to coach the team through the 2018 season, even as his team dwindled to 11 players — two of whom are his sons. The University chose to place Meehan on administrative leave only after another complaint was filed on March 23, before eventually electing to terminate the coach. Meehan could not be reached for comment as of press time.

Former Title IX Coordinator Linda Shinomoto, the original human resources representative on the case, left the University suddenly in the middle of the investigation to join the Wentworth Institute of Technology. She was replaced by Vice President of Human Resources Robin Nelson-Bailey. Nelson-Bailey declined to comment for this article, referring the Justice to the Office of Communications.

Though he noted that fair investigations “can take time,” Liebowitz wrote in a follow-up email on April 6 that “the process did not work the way it should have for the students who filed complaints. This cannot and should not happen again.”

To that end, the University has retained former assistant United States attorney for the District of Massachusetts Walter Prince — partner in the Boston law firm Prince Lobel — and the Honorable R. Malcolm Graham, a retired associate justice on the Massachusetts Appeals Court who is now at JAMS, a mediation and dispute resolution provider. The two will lead an independent investigation, which will focus on this case and similar ones; review the University’s systems, climate and handling of complaints; and recommend actions and changes, acording to the April 6 email.

The investigation may take some time, Liebowitz said in the joint interview. “You could have a quick review, but it won’t be thorough, and I think what you need is a thorough review,” he said.

When asked in the interview who initiated the external investigation, Liebowitz responded, “I did. It was my decision to take this, because the more I learn, the more I see that there are issues, deep issues, here that we have to get at.”

The investigators have set up an office in Goldfarb Library, where community members may go to give statements and information pertaining to this case and others.

Pending the investigation, Athletic Director Lynne Dempsey ’93 was put on administrative leave, with Assistant Athletic Director and Swimming and Diving Coach Jim Zotz filling the position in her stead. Dempsey could not be reached for comment as of press time.

“We have a responsibility to provide everyone with a safe environment,” Liebowitz wrote on April 6. “We must and will do better.”

‘If he targets you ... he will use anything.’

While the recent complaints brought new attention to Meehan’s coaching, his behavior is not a recent development; students complained to administrators about the coach’s treatment of his players as early as 2014.

At one practice in January 2013, Meehan called Ryne Williams ’16 a “motherfucker” for his performance, according to an April 10 Deadspin article. Williams suffered as a result of Meehan’s treatment, the article notes; his academics began to slip as he became depressed.

“There’d be this inconsistency,” said Phil Keisman ’07, who served as a student manager under Meehan from 2004 to 2007. “You wouldn’t really know what to expect from him, though I got a sense toward my senior year how he would respond to guys.”

Meehan could be capricious, often relying on intermittent reinforcement and public shaming to keep his team in line, Keisman said in an interview with the Justice.

“For me, it meant that he would find opportunities — often public opportunities — to shame in ways that often never really had to do with work,” he said. “The feedback, which was always public, often had to do with religion — being a Jew — and also body type. I was the manager among athletes, so that was sort of an easy one.”

As one of the few Jews involved in the team, Keisman earned the moniker “Jew Boy” from Meehan.

While Keisman did not notice a difference in Meehan’s treatment of white and Black players at the time, he said he was not surprised to hear of the allegations of racially biased harassment.

“I could totally see how after 10 years of never really being called on it, that kind of stuff could be happening and coming out,” he said, adding, “In retrospect, as I look back, I’m like, ‘Oh, shit! There were guys leaving the team, there were guys who were sullen. What was he saying to them behind closed doors? How were the public shamings that he was doing with them landing?’ At the time, I was so focused on myself that I didn’t notice how it would have impacted other guys.”

Meehan’s use of race-based harassment fit into his overall style of intimidation and abuse, Keisman said.

“I think he’s a man who will ... — if he targets you, … he will use anything,” he said, adding that Meehan also kept players in line by reminding them of their place.

“One of the things I think he did really successfully … is I think he set up an environment where, because compliance and hierarchy were so important, there was not even a thought of shaking up the order,” Keisman said. “And he was so in control.”

“The unspoken sort of thing was if you leave your place, you risk not getting it back,” he added.

On one occasion, Meehan told Keisman that he risked losing his team position if he studied abroad. So Keisman didn’t, instead looking forward to the team’s training trip to Italy in the summer. On the trip, everyone on the team — coaching staff included — received a bag of men’s basketball apparel and giveaways. In the airport on the last day, Meehan sent an assistant coach over to Keisman to collect only Keisman’s men’s basketball apparel, claiming that he wanted to wash it and give it to new recruits.

“He wasn’t going to give them to anybody,” Keisman said. “It kind of felt like a way to remind everyone around me of my place, and to … sort of stick it to me one last time. It just felt like it was a cruel thing to do.”

Open meeting

Moving forward, the University will look to improve the policies, procedures and campus culture that allowed Meehan’s behavior to go unchecked for years.

Emphasizing the need for an “open and honest” conversation, Liebowitz announced in his April 6 email that there would be an open town hall meeting in Levin Ballroom on Monday, April 9. The meeting, attended by students, faculty, staff and some alumni, was helmed by Liebowitz, Provost Lisa Lynch and Board of Trustees Chair Meyer Koplow ’72. The investigation, Liebowitz announced at the meeting, will begin with the Athletic Department and trace back to other areas in the administration.

Touching on the existing complaint policies, Prof. Michael Rosbash (BIOL) said at the forum that it was “absolutely ludicrous” that the investigation took six months, and that “everyone is a victim here” as a result of a drawn-out process.

Rosbash, who served as an adviser to Meehan during the investigation process, added that he believes the problem on campus is not so much racism as inadequate employees and administrators.

“With respect to the culture, … I don’t see a tremendous plethora of racism on campus, and I include the Athletic Department,” Rosbash said. “That isn’t to say it’s zero. It’s not zero, it can’t be zero, it will never be zero.”

“Is the goal to reduce the incidences of racism to zero on the campus?” he asked, prompting several cries of “yes!” from the audience.

“Of course it should be zero,” Rosbash conceded. “It’s an abomination, there’s no question about it. Nobody disagrees with that.”

In a subsequent letter to the editor submitted to the Justice, Rosbash wrote that he regretted that his comments at the meeting downplayed racism on campus, adding that they came from a place of “frustration and pessimism about the country we currently inhabit.”

Shaquan McDowell ’18 also addressed administrators at the meeting, saying that he was disappointed but not surprised by the whole affair. He emphasized the importance of factoring student voices into the upcoming investigation process, explaining that students are experts in how campus culture can be improved.

But the University has long promised significant change, and it has long failed to deliver, asserted Chari Kariyana Calloway ’19, who participated in the Ford Hall 2015 protest.

“What are y’all waiting on?” Calloway asked. “Does somebody, like, actually have to die?”

She asked what tangible actions the University has taken to improve the campus in recent years. “We have failed,” Lynch admitted in response.

“The goal is zero, and the goal is not a goal that I hope we get to in 50 years’ time,” Lynch said, emphasizing the sense of urgency. “That goal is something that everyone in this room should be committing to and working to. … And we have not done it as a community.”

In the joint interview, Liebowitz added that the University has taken some steps to make Brandeis more inclusive. Liebowitz stated that the administration would put up a website on the investigation and the issue at large that would feature some of these implemented changes. This website was activated on Tuesday, April 10.

“As I think Lisa tried to explain [in the meeting], … several things have been done,” he said. “They haven’t been communicated necessarily all that well, but this website will have on it some of the things that have been implemented and that move towards some of the big challenges we face.”

Other speakers expressed frustration with the University’s lack of transparency through the initial investigation process.

“What am I missing about ‘zero tolerance’?” Daniel Parker ’21 asked Liebowitz, citing the discrepancy between the University’s stated harassment policy and the one-strike disciplinary action handed down initially. “What does it mean in Brandeis language?”

Above all else, though, the community members who spoke at the forum emphasized that the issue of racism on campus extends beyond Meehan.

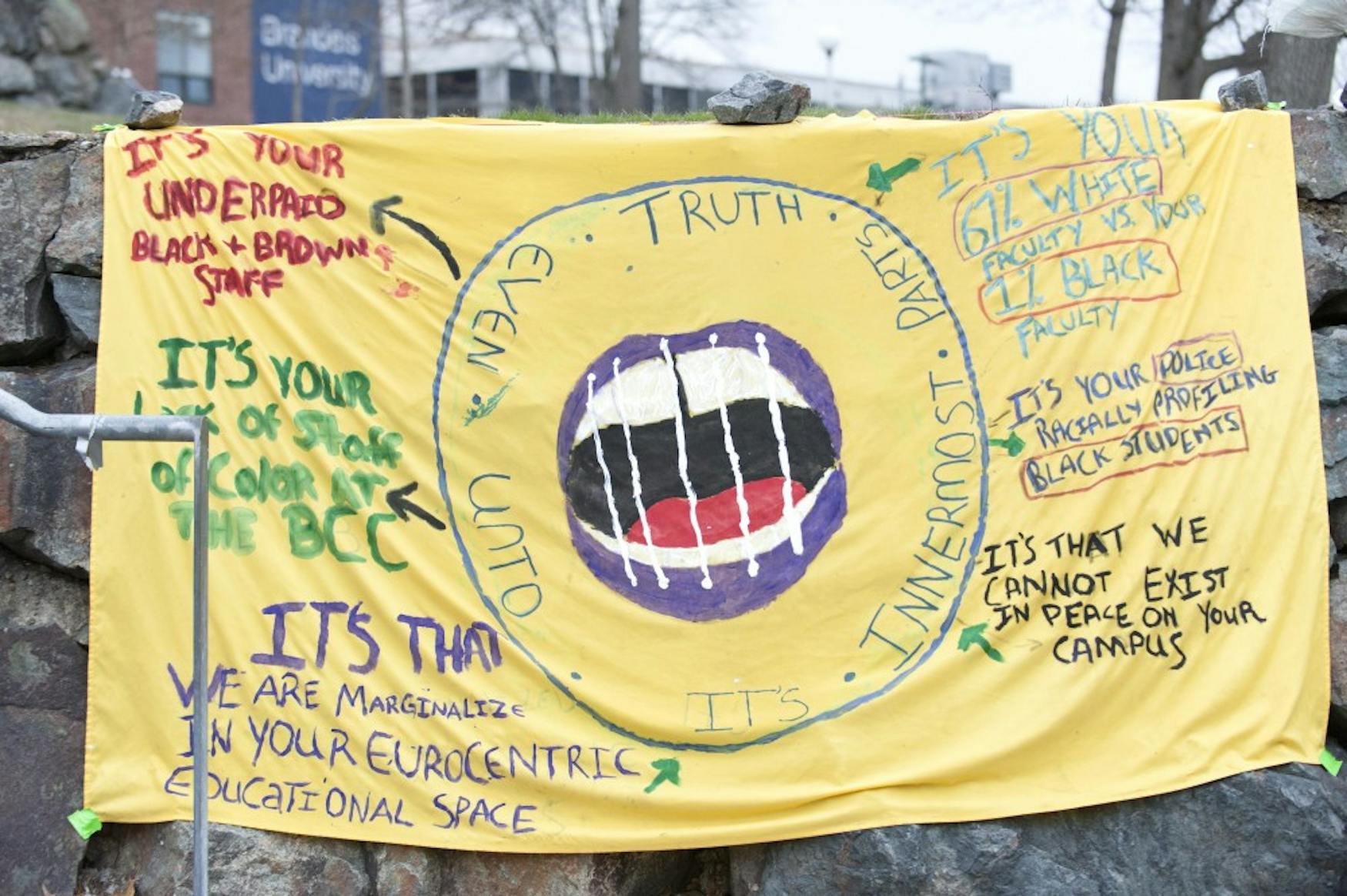

This sentiment was made tangible the next day in the form of two banners, spread across the Rabb steps. One highlighted statistics about people of color on campus. “More Than Your Racist Coach,” the other banner read.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.