This is ‘Why Amy Beach Matters’

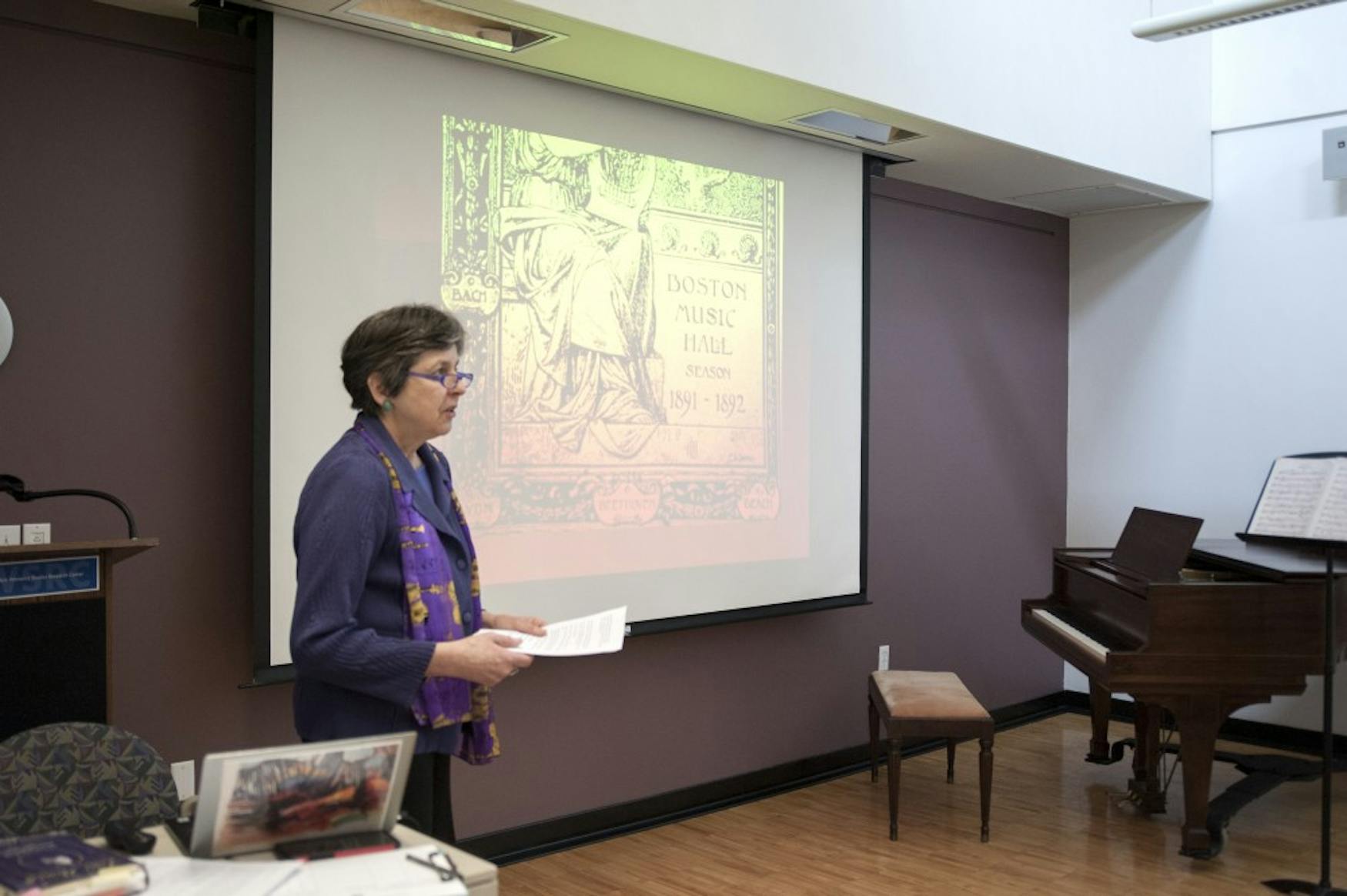

“You think the glass ceiling is shattered only to realize it’s just been cracked,” said musicologist Liane Curtis in her presentation “Why Amy Beach Matters” last Thursday, in the Women’s Studies Research Center. Amy Beach (1867-1947) was an American composer and pianist. Curtis, who earned her doctorate in musicology from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, is a resident scholar at the WSRC.

What I come away with from Beach’s music and Curtis’ presentation about the woman herself is that Beach was defined by chapters. Curtis’ presentation was bookended by performances of Beach’s works by violinist Carol Cubberley and pianist Sandy Lin. Listening to Beach’s compositions “Romance” (1893, Op. 230) and “The Second Movement of the Violin Sonata” (1896, Op. 34) was a truly sublime experience. I identified and was struck by melodic and harmonic moments in her compositions that I rarely hear in more popular and widely known pieces written by the male musical masters who were, and still are, given more attention because of their gender. In both “Romance” and the second movement, a musical resolution did not mean peace and finality. As the melody of the violin reached resolution, the piano would continue on, unsatisfied with the newfound tranquility. The resolution of one section built upon and evolved the melody, tonicizing to a new key to begin a new musical idea. While listening, I got the sense over and over again that, for Beach, chapters in life do not mean the end; they morph and transition to be a part of a new moment.

As Curtis took us on a fascinating journey through the life of Amy Beach, I was struck by how she was treated as “less-than” by her family and the musical scholars she came in contact with despite the fact that she was clearly one of the most naturally, or “freakishly,” as Curtis put it, talented and musically inclined human beings of her day. She was married to Dr. H.A. Beach, who restricted her live performances and asked her to focus instead on composition. Curtis pointed out that this could be viewed as his attempt, as her husband, to keep her out of the performative spotlight and, by extension, away from the leering eyes of other men. This was a double-edged sword for Beach. She loved performing but knew that as a composer her husband’s connections with the sheet music publishers would be an invaluable asset. By the time her husband died, Beach and her compositions were an international sensation. It was because of this that she kept her husband’s last name, but in a proto-feminist move changed the creditson her sheet music from “Mrs. H.A. Beach” to simply “Amy Beach.” The crux of Curtis’ presentation was that even though Amy Beach was one of the most famous and influential composers of her day, her gender stopped her from reaching the level of influence and fame of many of her male contemporaries and predecessors.

2017 marked the 150th anniversary of Beach’s birth. Now, in 2018, we here at Brandeis celebrate the 100th anniversary of composer Leonard Bernstein’s birth. Without discounting the talent and influence of Bernstein, one has to question how gender plays into history and who is remembered and celebrated. The good news is that our modern sensibility when it comes to art, politics and the professional world in general is beginning to reach beyond historically typical boundaries. We still have a long way to go in making sure that everyone’s voice is heard. However, Beach taught us that you should not let how society views you, whether it be because of your race, gender or social class, stop you from pursuing your passions.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.