Scholar explores Iranian prisons’ societal impact

For scholar Golnar Nikpour, the idea of prison — especially in Iran’s Pahlavi era, 1925 to 1979 — is so much greater than criminal punishment; Iranian prison, she argued in a seminar on Wednesday, has historically been an educational institution.

Nikpour, the Neubauer Junior Research Fellow at the Crown Center for Middle East Studies, has written a book about Iran’s prisons, penaly and criminal systems.

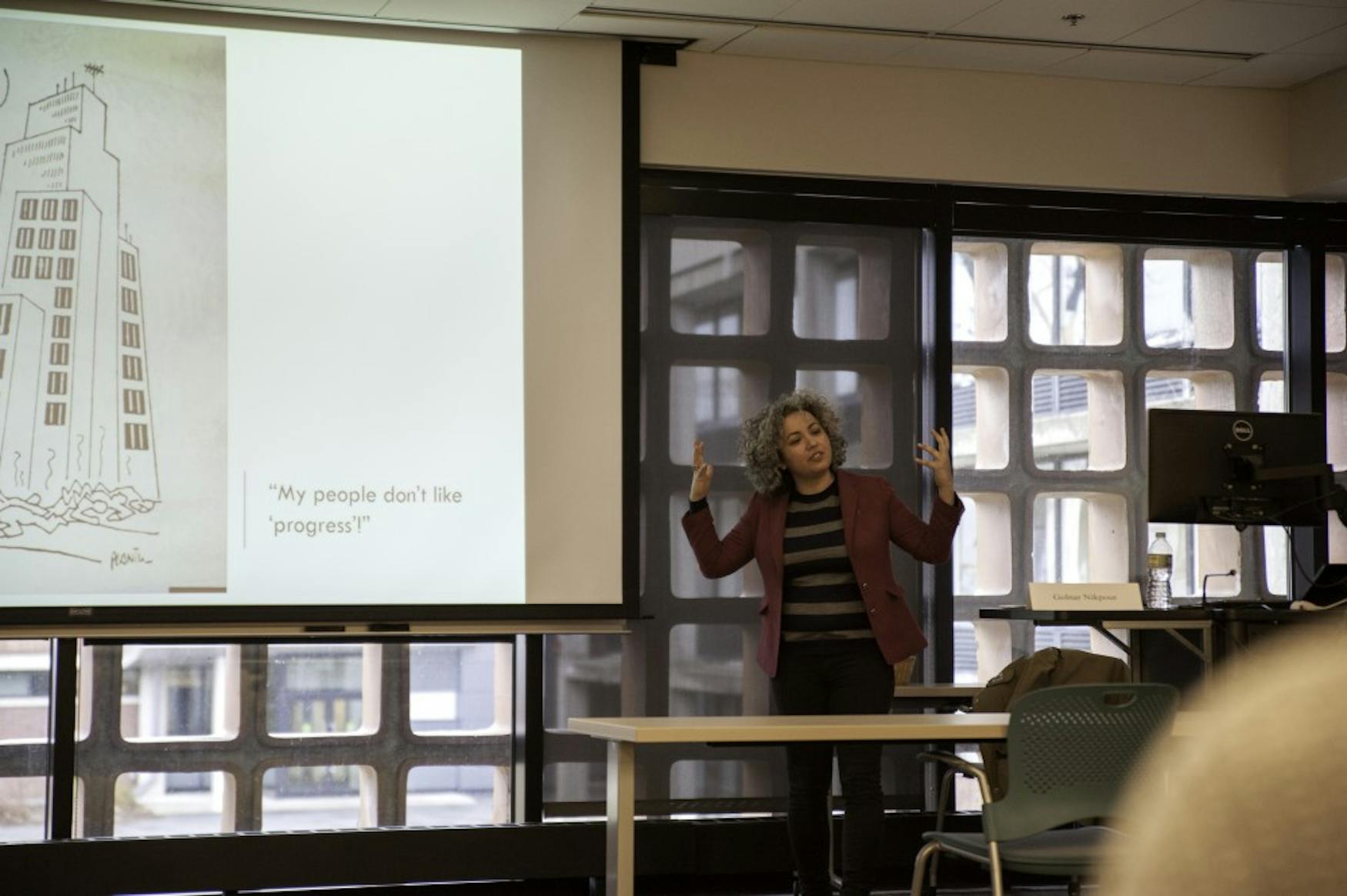

Nikpour discussed what prisons stood for and what they brought to Iran, giving the audience insight into the social context of that period. She began the talk by arguing that prison was treated as educational and served as a center for social reform for many prisoners.

She quoted leftist Iranian political activist Bozorg Alavi to demonstrate such a belief: “Prison, for us, was truly a school. We learned many things there. Not only about social and political matters, but also… well, what didn’t we learn? For example, I learned Russian in prison. I learned English in prison. In prison, one read in earnest,” Alavi said in a 1985 interview.

Nikpour mentioned Alavi’s memoir and pointed out that he is not the only one whose experience demonstrates this fact. She explained, “Nearly all opposition parties in modern Iran produce work from or about prison.”

Nikpour then talked about her work on the topic. “My work is an inquiry on the nature of the power of the modern state, and I argue that both techniques of punishment, as well as response to those techniques have developed and vary over time.”

Adding to this, she spoke of the importance of viewing punishment practices as interconnected, rather than separated by the philosophies of the governments which implemented them. “Punishment techniques are not natural, stable outgrowths of forms of governance,” she said, “but are rather historically contingent practices that fluctuate and evolve in a shifting arsenal of modern power.”

“That is,” she continued, “we cannot speak coherently of ‘fascist punishment,’ ‘liberal punishment,’ ‘nationalist punishment,’ ‘Islamic punishment,’ [and so forth].”

Cultural languages of modern punishment are “transnational and linked,” she said. She pointed out that Iranian prisoners read materials by activists and prisoners all over the world, including those outside Middle East.

Incarceration tends to be a “global phenomenon,” which is not necessarily addressed by current scholarship, Nikpour emphasized. She believes that people should “not simply examine regimes of mass incarceration in local context” but also “contextualize them in the transnational networks in which they have emerged.”

There are some detailed examples, especially from the Pahlavi period, which support this concept, she added. Nikpour discussed some big transformations from this period, showing photos depicting the state of the prisons and the imprisoned: what they dressed in and the what those prisons looked like.

Yet, prisons were also handy for another form of education, Nikpour asserted: teaching prisoners how to develop their criminal skills.

She made critiques of Pahlavian Iranian prisons, which argued that even female or juvenile prisons served as places where elder prisoners teach younger ones to commit crimes.

These critiques pushed prisons to require work from their prisoners in order to keep them out of trouble, according to Nikpour.

Discussing her work with previously unexamined scholarly sources on criminology and criminal sociology, Nikpour told audiences about an early 1950s doctoral thesis, “Prisons and Prisoners,” by an Iranian at Tehran University’s law school.

“From what I discovered, this is the earliest academic work that focuses exclusively on prison,” Nikpour said, adding that the thesis’ author claimed that “the history of punishment moves as a progressive march from an inefficient and inhumane towards one useful and just.”

Nikpour added that the author wrote, “in prisons of old … the prisoners will be forced to confess whether or not they had committed any crime. But in today, in Iran, punishments are applied in regard to the law.”

Nikpour also quoted a criminology expert who said, “The criminal is like a patient, and just as a doctor orders tests on the patient in order to diagnose their disease, the judge must collect information on the personality of each offender, in order to discover the reasons … for their crime.”

The medicalization standpoint, according to Nikpour, is necessary “because prisoners were both imagined as a vulnerable population in need of care and as possible social contagions.”

“If crime was the illness,” said Nikpour, “then prison would be the cure or, at least, the quarantine.”

Nikpour further discussed this topic in the context of revolutions and revolutionary groups during the 1970s, in the last decade of the Pahlavi era.

Nikpour also discussed post-Islamic Revolution Iran. She explained that the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the revolution’s leader who overthrew the Pahlavi regime in 1979, said that “no person could be executed except when a person has ordered a massacre or act of torture.” She also discussed her perspectives on tortures and interrogations against political prisoners.

The talk concluded with a question-and-answer session with the audience.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.