Scrutinize Nobel Peace Prize candidate vetting process

And the results are in! For the 2015 year, Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe has been declared the winner of China’s Confucius Peace Prize for the Founding Leader as “he brought benefit to the people of Zimbabwe.” This benefit so frequently manifests itself in the presence of mass atrocities and election violence, but maybe for a moment let’s put that aside to reevaluate how we got here.

The prize was first awarded in 2010 in response to the Nobel Committee’s choice to give the Nobel Prize to Liu Xiaobo, a Chinese dissident who spent 11 years in prison. The Chinese government believed it was high time for them to start awarding accolades for what Qiao Wei, a poet and president of the judging committee, said in an interview with the New York Times is this century’s interpretation of Confucianism: the “concept of universal harmony in the world.” This has compelled them to award the prize to the likes of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, agricultural scientist Yuan Longping, Zen master Yi Chen and former Cuban President Fidel Castro.

With such a spotty record, how can we expect China to actually award those who appear to be truly deserving of such an accolade? Or can we really argue it is worth anything? Well, with Mugabe in mind, perhaps everyone should have little faith in the process. While credited for his pan-African attitude in the wake of the colonial era, the despot isn’t shy about allocating his own brand of atrocities such as the “Gukurahundi massacres,” where Mugabe’s army is credited with slaughtering 20,000 innocents in an effort to weed out the opposition, or the more recent violence and intimidation encouraged by the 2008 run-off in elections. Being paired alongside changemakers like Yuan Longping doesn’t amplify the image of Mugabe, but rather, it goes to further delegitimize the peace prize.

Judgement of the Chinese selection process aside, maybe we should begin to recognize that they did something right, albeit for the wrong circumstances. Maybe the selection process for Nobel Peace Prize winners is fundamentally flawed.

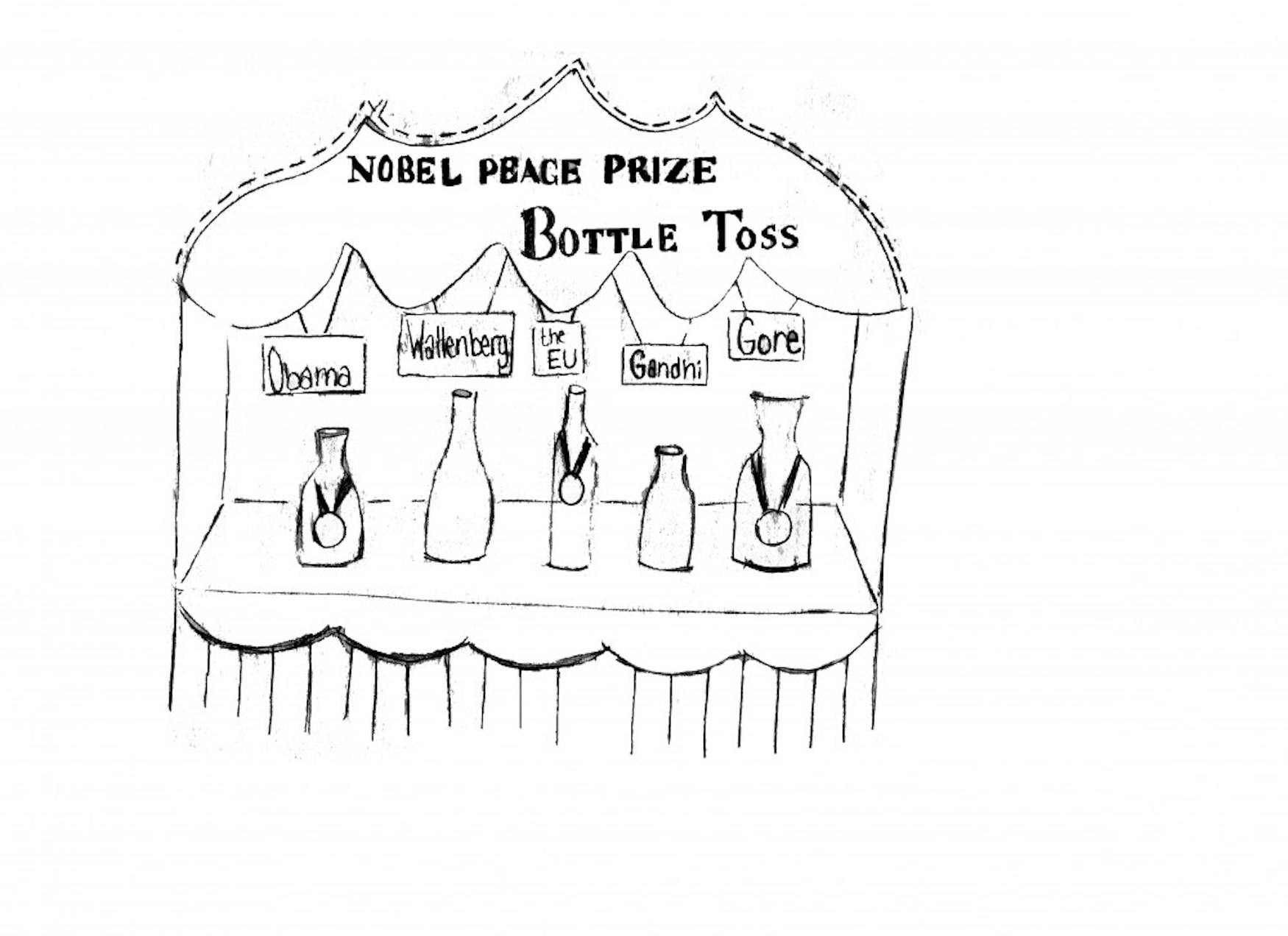

Often, those deserving of the Nobel Peace Prize — despite being nominated for it on multiple occasions — failed to obtain the prize. Most notable of these nominees is Mahatma Gandhi, India’s pro-democracy independence leader who practically invented the non-violence movement. Gandhi was nominated five times between 1937 and 1945 and never recieved the prize. Instead, on the year of his death, the committee chose to pick no candidate. The peace prize was only awarded posthumously to two people, and in 1974, the Statutes of the Nobel Foundation ruled that no prize could be awarded unless the announcement had been given before the would-be recpient’s untimely death.

Another very deserving individual who was nominated for the prize multiple times but never received it due to similar circumstances is the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, the righteous gentile credited for saving tens of thousands of Jews in the closing months of World War II in Nazi-occupied Hungary. Wallenberg issued “schutz-passes,” or Swedish protective papers, to prevent deportation and he established Swedish safe houses that provided a neutral harbor for tens of thousands. By the second nomination, the diplomat was presumed dead in a Soviet prison. What happens when a person perfectly personifies the award? Gandhi is the father of the non-violent movement and Wallenberg sacrificed his life in the pursuit of peace. Wallenberg once expressed, “I will never be able to go back to Sweden without knowing inside myself that I’d done all a man could do to save as many Jews as possible.” Might I ask, who is more deserving of this prestigious honor than they are?

If it cannot get any worse, the international community has often administered the award merely as a symbolic gesture. Most notably after he spent only a year in office, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided to award the prize to none other than President Barack Obama in order to encourage him to further his goals of nuclear disarmament, according to Geir Lundestad, the director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute.

In 2013, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons “for its extensive efforts to eliminate chemical weapons” as yet another symbolic gesture. This event was particularly timely as the organization was responsible for ridding Syria of its stockpile of chemical weapons with the attack on Ghouta. Today, according to the New York Times, at least 984 civilians have been killed by exposure to chemical weapons or agents. This exposure is continued, and therefore, one can assume that the OPCW mission was unsuccessful.

The same year, Dr. Denis Mukwege, Congolese doctor and medical director of the Panzi Hospital in eastern Congo, was nominated for the award.

Women in the country travel hundreds of miles to receive medical care for vaginal fistulas as a result of rape and psychological treatment for wounds that can never be healed for Congolese women. Sexual violence in Congo is so prevalent that it is to be expected. In fact, in 2010, Margot Wallstrom, the UN’s special representative on sexual violence in Congo named the Democratic Republic of the Congo the “rape capital of the world.” Despite all of this, and after three nominations, he has yet to receive the Nobel. In 2012, armed gunmen broke into the home of the man who is credited with saving tens of thousands of women. It would certainly be a shame if his work is never recognized.

Perhaps Mugabe winning this Confucius Peace Prize will open our eyes to the inherent flaws in a prize we deem so significant to our global order: the Nobel Peace Prize. This prize should be exclusive to those reexamining this global order, attempting to return to peace and realizing that living is about what you can give to someone else.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.