POINT/COUNTER-POINT: Adjust Cuba policy to improve US-Cuba relations

On Dec. 17, President Barack Obama announced that after 53 years, the United States will resume diplomatic relations with Cuba and reopen its embassy in Havana. His announcement marked the first diplomatic arrangement between the countries since the Cuban Revolution in 1959. This arrangement severed all relations between the U.S. and the Soviet-supported Cuba. The president noted that this decision aims to end the bitter past that had ensnared the two North American neighbors for more than half a century. He also stated it would utilize a new approach for political and economic change in the island nation.

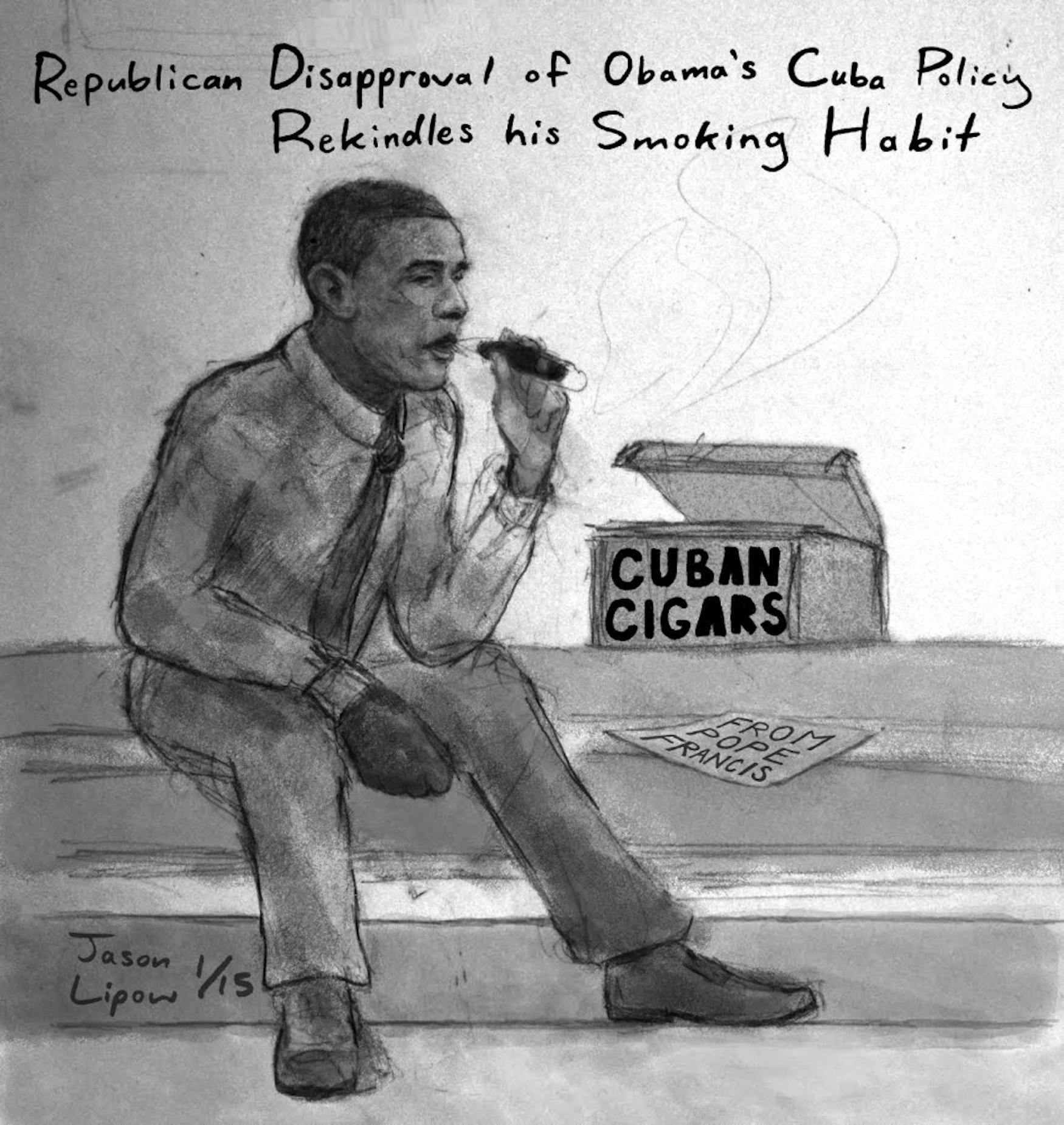

Expectedly, a number of observers have criticized the president’s decision. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) remarked that the reestablishment of relations will do nothing to improve Cuba’s human rights record. Instead, opening relations will allow the Cuban government “the opportunity to manipulate these changes to perpetuate itself in power.” Despite such criticisms, the normalization of Cuba-U.S. relations is right for the U.S. and is in the interest of both countries.

By normalizing diplomatic relations, the U.S. and Cuba will once again have a formal channel they can use to communicate and negotiate with each other. The U.S. can help an economically stagnant country and its people revitalize their economy and begin talks for easing the current U.S. embargo on Cuba. For 53 years, Cuba and the U.S. had virtually no policy dialogue.

The embargo restricted the Cuban economy from accessing many U.S. resources and goods, such as infrastructure components, food and medicines. Ultimately, the embargo has failed in punishing and removing the Castro regime. Instead, it punished ordinary Cubans, who suffered the most as infrastructure and standard of living deteriorated.

Of course, the Cuban government must make its own economic reforms too, such as further liberalizing its state-run economy and introducing more free-market reforms to spur investment. But the U.S. should not make the task more difficult for the Cuban people. Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla cited that since the start of the embargo, 76 percent of Cubans have suffered economically. The country has lost one trillion dollars from the half-century embargo, which has denied Cuba of the opportunity to raise its living standards. Loosening the embargo could introduce benefits of increased investment and trade to Cuba and even persuade the government that more advantages than disadvantages will come from greater economic reform.

In the ongoing negotiations, the U.S. has agreed to lift or relax a number of its restrictions on American activities. Rules, like restricting family visits between the two nations, have dissipated. Also, the president will relax restrictions on American banking and commerce in Cuba, allowing Americans to use credit and debit cards for purchases in Cuba and to bring certain goods back to the U.S., including Cuban tobacco and alcohol.

Although tourist travel to Cuba was not included among these new policies, they provide hope that relations will improve with time. By allowing greater American commerce and investment in Cuba, the country will receive much needed revenues and resources to reinvest in its own economy, allowing ordinary Cubans to raise their standard of living. Additionally, by relaxing restrictions on family visits, the U.S. will not only allow long-separated families to reunite more easily but also better facilitate the people-to-people contact required to repair the severed relations between Cuba and the U.S. that have bred misunderstandings and hostilities between the two peoples. On a person-to-person basis, Cubans may better see that ordinary Americans are not the devils the government has portrayed for more than 50 years.

Moreover, the U.S. has normalized relations with former enemies such as China and Vietnam, communist countries known for their Cold War anti-American views. Normalizing relations had created new economic partnerships between the U.S. and these countries and helped to diminish the legacy of constant hostility and security threats for America and its new partners. If the U.S. could establish relations with China and Vietnam, there is no reason it cannot do the same with a country that is only 110 miles away.

Additionally, normalizing relations with Cuba will improve America’s image as a nation willing to cooperate and make amends with other countries. A bitter, unchanging stance towards Cuba may only exacerbate America’s image as an uncompromising power that cares little about its relationship with the rest of the world. This image will not help the U.S. when it needs to negotiate and cooperate with other countries. Fostering a better relationship with Cuba instead can persuade America’s allies and partners that the U.S. is willing to work with other countries to find solutions to common problems.

Critics of the normalization, such as Senator Rubio, have claimed that this decision will do nothing to improve human rights and promote freedom and democracy in Cuba. Former Florida governor Jeb Bush even criticized the decision as a setback in advancing freedom and democracy on the island.

Despite such criticism, there are more long-term advantages than disadvantages that come with normalizing relations. The embargo is not consistent with past American foreign policy decisions either. The U.S. normalized relations with other former enemies, such as China and Vietnam. By normalizing relations, the chance for democracy may actually improve.

With China and Vietnam, normalized relations have allowed freer exchange of people, goods and ideas between countries at the grassroots level and helped to build a populace that is better informed about the world. In turn, this change has incentivized the authoritarian governments of these countries to become more attentive to the demands of their people.

Increased intergovernmental dialogue and cooperation can allow the U.S. to better insist upon incremental political reforms too; the U.S. can offer economic assistance in exchange for policy changes. It is an alternative to incentivizing reforms through sanctions, which not only have been ineffective but also have increased tensions. Political change ultimately must come from within Cuba itself, but better relations with Cuba can plant the seeds for that change.

Half a century of embargo towards Cuba has not yielded positive results for either country. Therefore, the U.S. needs a new approach in its relations with the island if it still wishes to see change in the country. Change will come only when both sides are willing to cooperate, and the U.S. should do its part to compromise and help foster that change.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.