Novelist makes her debut

As a Brandeis undergraduate on the pre-med track, Nadia Hashimi ’00 didn’t imagine her professional life would turn out as it has. Literature was always something she appreciated, but it wasn’t until she’d settled into life as a doctor that she realized she could pursue writing as a second career.

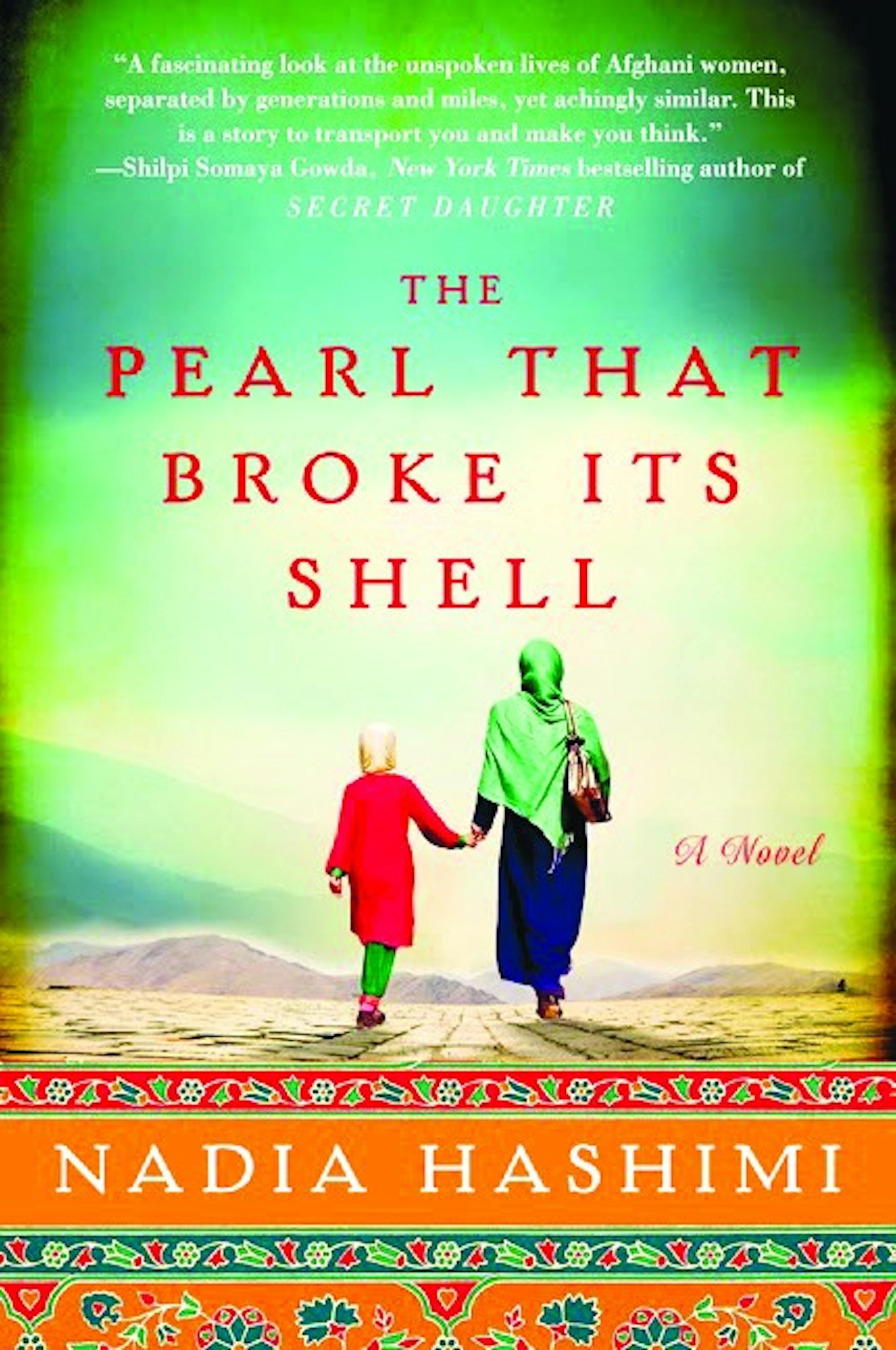

In May, Hashimi debuted her first novel, The Pearl that Broke Its Shell, a book that explores a unique cultural phenomenon that at once sheds light on the particular struggles of Afghan girls while commenting on the universal inequities of women worldwide.

The novel oscillates between the stories of two girls of the same lineage, separated by generations but linked through a relatively common and normalized practice in Afghanistan known as “bacha posh,” in which families without sons will disguise one of their daughters in order to elevate the status of that family and give the girl an higher degree of personal autonomy.

The novel is focused on a adolescent girl named Rahima, a modern-day, former bacha posh who struggles to adapt to married life as a young adolescent, and Shekiba, Rahima’s great-great grandmother, an orphan living in early 20th century Afghanistan whose life is saved by the same custom.

Although Hashimi has always loved reading fiction and maintained an interest in the Middle East that was reflected in her coursework, her primary career goal while she was a student was to attend medical school. Hashimi said that the decision to major in Islamic and Middle-Eastern Studies “opened my eyes to literature in that part of the world,” while her second major in Biology allowed her to complete the necessary prerequisite courses for medical school.

As an Afghan American, Hashimi’s family preserved many traditional Afghan customs, including celebrating Ramadan and Nowroze, the first day of spring and the in Afghanistan. Yet although she felt connected to her Afghan culture, she did not make her first trip to Afghanistan until after she graduated college. “I wanted to go for myself and see what the country looked like; I wanted to meet some of my extended family members,” said Hashimi.

She went on to graduate from The State University Of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn medical school and complete her pediatric training at New York City hospitals. It wasn’t until she had been practicing medicine for a number of years that she began to consider a second professional life as a novelist.

Hashimi’s first trip to Afghanistan, with her parents in 2002, was unrelated to plans for a future book. But while her novel did not begin to take form until 2008, the trip would color and shape the story she wanted to tell. She visited local hospitals and schools during her trip, as well as many members of her extended family. “Seeing the young girls and how energized they were and how grateful they were to be going to school, that did influence what I ended up writing about. Those personalities are in the story,” said Hashimi.

In terms of research, Hashimi relied on recollections of her trip to Afghanistan and personal accounts from family members for the modern day sequences. Primary research and textual sources informed the part of her book that took place in the early 20th century.

Her interviews with relatives revealed the modern Afghan stance on bacha posh and emphasized a stark contrast between how it is viewed in the Western world and in the Middle East. “Not everyone will do [bacha posh] but it’s something that everyone knows about,” Hashimi explained. “It’s not really all that secret over there. It’s kind of one of these above ground practices and everyone understands why people do it, so it’s not really questioned and it’s not looked at critically,” she said.

Hashimi’s personal view on the practice is complicated. “If you have to dress a girl as a boy to restore honor to your family and will allow her the simple liberties of going to school, or going to the market, or having a conversation with someone eye to eye, then clearly you have a huge gender gap and women are devalued in the culture. That being said, the bacha posh tradition has some benefits for a lot of these girls,” Hashimi said.

Hashimi went on to explain that “a lot of [Afghan girls] have gone on to build up that confidence that a boy would have, and they’ve gone on to become professionals, leaders, have roles in politics and government. Many of these girls refuse to get married because they say they can never go back to a role where they are like basically considered a second class citizen,” Hashimi said.

For Hashimi, the bacha posh tradition was a vehicle for speaking to larger social issues in Afghanistan and beyond.

“For me, the bigger concept is about what it means to be a girl in Afghanistan or any society where there’s a large gender gap,” she said.

The modern portion of The Pearl that Broke Its Shell takes place shortly after the fall of the Taliban regime, where, amid continued fragmentation and corruption, the government is showing semblances of order. There are signs that the tide might finally begin to turn for women in the country, but old traditions hamper progress.

Hashimi spoke to what she sees as the biggest problem facing equal rights for women in Afghanistan, saying, “It’s a big deal to change the mind-set of the country so that people can accept that women should be in the public forum and that they should be involved in government and that they should have a role outside of their home,” said Hashimi.

In addition to her heritage, Hashimi’s job as a pediatrician may have also influenced her novel. “I look at children, I wonder what they’re thinking sometimes. ... A lot of the challenges I see in pediatric patients here have translated into me writing about how it affected the younger people in the novel.”

Hashimi described her current life in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. as a juggling act.

In addition to her life as a novelist, she is a mother of three, and she maintains part-time work as a pediatrician and helps manage her husband’s medical practice.

She is currently in the process of revising her second novel about the plight of Afghan refugees in Europe.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.