Battle directs Ailey Co

Dance is an art of the present. Unlike film, literature or painting, it thrives on live performance. Its emotional and aesthetic effects are lost when seen on footage or, admittedly, recounted in a review. Why, then, has Alvin Ailey's "Revelations," a transcendent hymn to the African-American spirit, become timeless since its debut in 1960? Why are these movements and images, among the thousands of modern dances since created, worth performing over and over again?

Robert Battle, the new artistic director at the Alvin Ailey Dance Company, offered an answer with last weekend's programming at the Citi Performing Arts Center's Wang Theatre (the last performance was on April 29). As proof of Battle's innovative vision, each night brought new dances for the company, including works by choreographer Paul Taylor. More important, as proof of Battle's deference to legacy and history, he ended each night with Ailey's "Revelations." He said in a phone interview that the inclusion of "Revelations" was a "no-brainer." It was an obvious, yet insightful decision.

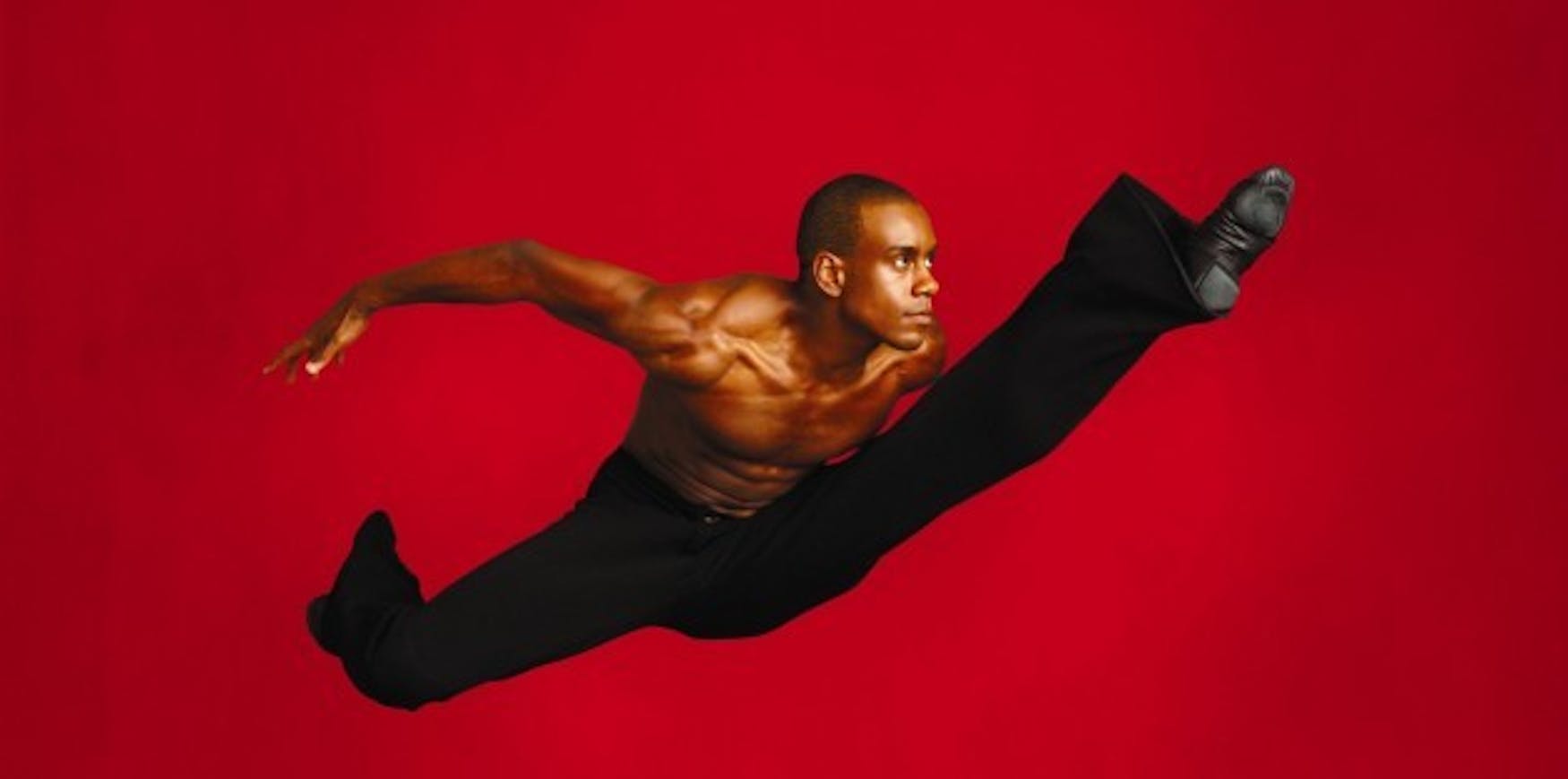

Battle decided to become a dancer after seeing "Revelations" performed in Miami, Fla. when he was 12. He went on to study at The Juilliard School and in Ailey's junior dance company, Ailey II. He also formed his own dance company, Battleworks. After a year of training, he officially became the new director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 2011. By succeeding the great Judith Jameson-who succeeded Ailey-as the company's new leader, Battle fulfilled a Hollywood-esque dream. He has spoken of his excitement and his gratefulness to that inexplicable thing artists like to call luck. He has also discussed his flat-out lack of nervousness as the new artistic director.

Battle took the stage with that same willful exuberance to preface last Friday's performance. After welcoming the audience like a friendly uncle at a Thanksgiving dinner, Battle made way for Taylor's "Arden Court," a classic 1981 piece of hedonistic innocence, if there is such a thing. A rose shines in the backdrop as two intersecting beams of light give the dancers a path to the front of the stage. William Boyce's symphonies fill the theater. The music is something you'd hear at the coronation of a Renaissance king. The royal introduction complements the Wang Theatre's lavish artwork and golden architecture. If dance is a transportation of the mind and soul, then the Ailey company took audiences to some faraway place during "Arden Court."

Ohad Naharin's "Minus 16," sounds like a surprise for Ailey on paper. The famous dance by the Israeli choreographer features dancers in formal dress engaging the audience by inviting them onstage. Ailey had never done anything like that before, Battle said in a question-and-answer session after the performance. It worked. From its tribal opening scene, in which dancers gyrate on chairs placed in a half-circle, to its jittery climax of improvised dance, the Ailey company made each move a highlight.

Because of the audience interaction, "Minus 16" was the most popular featurette of the night. But "Revelations" was the most important. From beginning to end, the dance was virtually unchanged from the 1960 version, and rightly so. The introduction, titled "Pilgrim of Sorrow," imbues the stage with spiritual purity. How could this classic be any better if it were different?

A church choir standing in the shape of a flock of birds raises their arms in prayer, or in flight. One dancer offsets the unity of the congregation-the uniformity of choreographed dance. A woman raises her hand in abrupt jerks while everyone else reaches skyward in a smooth motion. This is a wonderful thing about modern dance. While any dancer knows that movements are only effective if performed in unison, sometimes bending the rules is better than following them. As a result, out of the congregation, we see the individual. The dancers, previously seen as movable parts within a great machine, are now broken, unique pieces. Of course, underneath the celebratory innocence of "Relevations" is a story about slavery. Underneath the migration of the group is the toil of the individual.

In that sense, "I Wanna Be Ready" is the dance's poignant climax. The solo is performed by Kirven James Boyd, an eighth-year dancer with the troupes who graces the front of the program as well as many billboards. A wide, yellow spotlight shines on Boyd as he spins, ducks, rolls, jumps and prays. The oval shape of the light, and the threshold between light and dark, form a boundary meant to be broken. But Boyd never steps out of the light for too long.

No doubt there were audience members present who simply enjoyed the dance for its visual effects. But a few viewers understood the company's historical significance. One woman at the post-performance talk said she saw the company every year since 1972. Roughly half of those performances were while Ailey was still alive, before he succumbed to HIV in 1989. I didn't have a chance to ask her about that. All she said, over and over, to Battle and the dancers onstage, was "Thank you. Thank you so much."

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.