A reconciliation of tradition and modernity

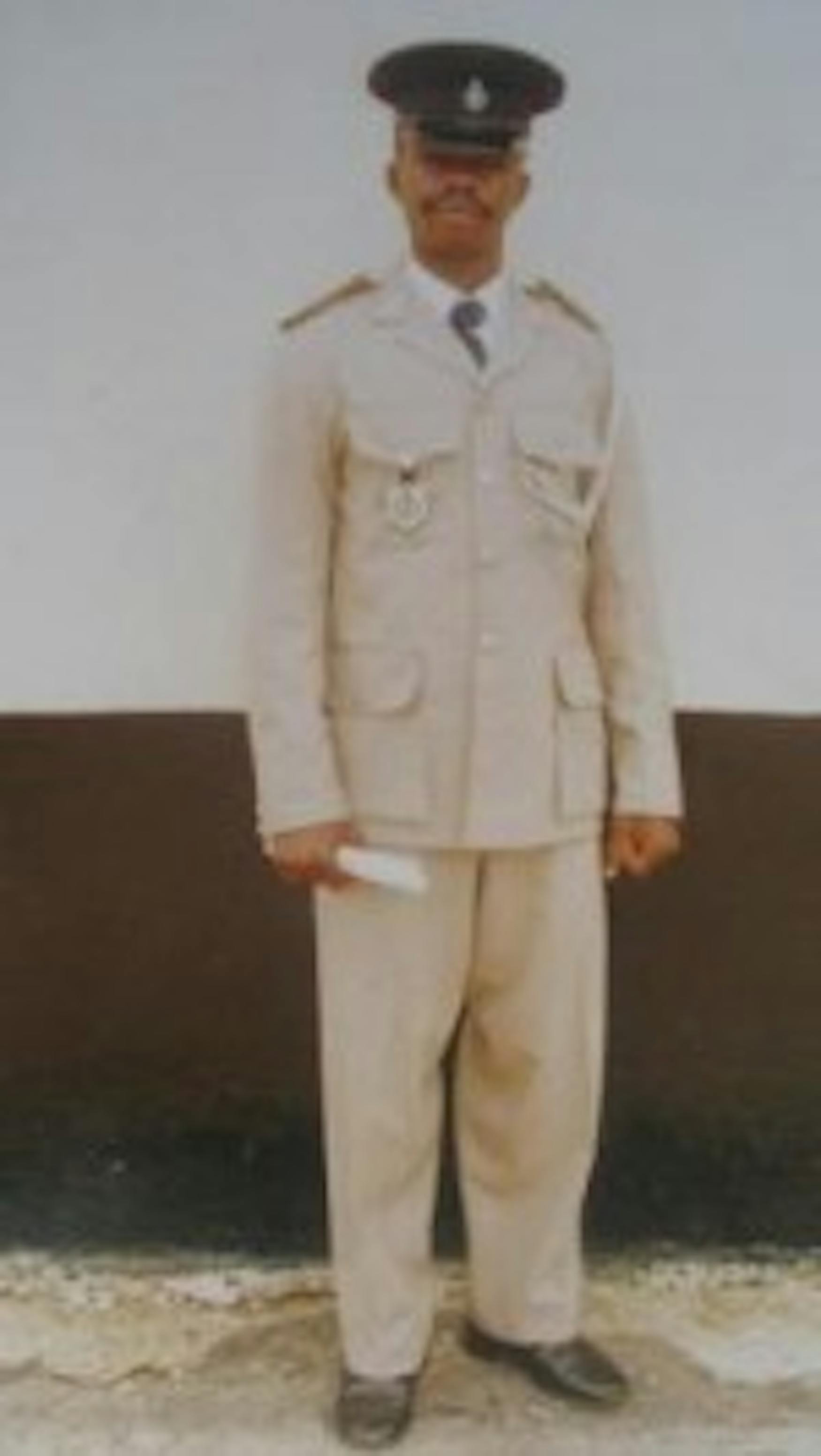

Jerome Kanyog (GRAD) works for peace training for police in Ghana

As Jerome Kanyog (GRAD) rides the Waltham shuttle to campus, he blends in with other Brandeis graduate students from overseas. He wears an indistinctive thick leather jacket, holds a briefcase and squints to prevent the gleam of reflective snow from obstructing his observant gaze. But Kanyog is different from other Brandeis students. At the end of the school year, Kanyog will not apply to internships or take time off to travel; instead, he will return to his job as a policeman in Ghana and work to help create the national police peace-training curriculum for the Ghanaian government. Kanyog, who is 41 years old and has been working as a policeman for 10 years, has been given a year of leave from the Ghanaian government to receive his Master of Arts in Conflict and Coexistence studies. He hopes to use his degree to develop a curriculum on peace education that will be incorporated into the training of reserves at the national police training school.

As a student, Kanyog has shed his gun and uniform in favor of notebooks and pens. While Kanyog has made some sacrifices in order to pursue his goal-he left his wife and twin toddlers at home-he believes that what he learns here will help police in Ghana understand how to respond to conflict.

"You are carrying a heavy, big responsibility. [You] need some form of training on how to respond proactively to conflict," says Kanyog of being a policeman.

Kanyog uses the metaphor of a fire to explain the necessity of peace training. "When there is a fire outbreak, whether the fire escalates or dies out depends on the reaction of the first person to get there-the first responder. The same is true in conflict."

Mari Fitzduff, director of the master's program in Intercommunal Coexistence and a professor of Coexistence, welcomes security officials into Brandeis' conflict management courses. Fitzduff also says the program has a component of mediation skills, which are now increasingly recognized as an essential skill for security forces.

"We always welcome people from the security forces-army or police-to our program on coexistence, as security forces have a critical part to play in all countries in ensuring social cohesion," says Fitzduff.

As a police officer, Kanyog often faces the challenge of having to reconcile between common, or federal, law and customary, or tribal, law. Although justice can be served according to either in Ghana, it is the duty of the police to enforce verdicts rendered by both judges. Still, common law supersedes customary law when they are in direct confrontation, as common law has labeled certain cultural or customary practices as illegal.

"Customary law is localized, not codified," says Kanyog. "There is often a level of subjectivity and arbitrariness. . In Ghana, the culture is so very strong and the people have a lot of close attachment to anything that has to do with the culture."

For example, one of the conflicting laws Kanyog encounters deals with marriage against a woman's will. While involuntary marriages are illegal under criminal law, customary law does not always prohibit them.

Another conflict arises following divorces performed by tribal leaders. In these cases, women are sometimes told that they must "purify" themselves. Although this "purification" is accepted under customary law, if the ritual she is commanded to perform is "dehumanizing," the state sees it as illegal.

Kanyog believes that in the future customary law must be codified. He also believes that the justice system must be consolidated, as tribe chiefs and kings are currently allowed to arbitrate disputes if they register with the state.

"There are so many places you can go for justice. [Often] there is a level of subjectivity and arbitrariness [in the ruling]," says Kanyog.

However, Kanyog believes it is impossible to disregard local traditions and customs.

"You can't just say, 'Let's abolish it,'" he says.

Nevertheless, many Ghanaians such as Kanyog will never choose to consult a tribal judge.

Kanyog has learned to be patient when explaining complicated and sometimes contradictory policies to Ghanaians who are sometimes illiterate. The care he takes to explain the government's position in rural Ghana has helped him to communicate complex issues to students here at Brandeis. He chooses his words slowly and deliberately when speaking.

Kanyog also has to deal with the issue of "chieftaincy," which he describes as one of the more difficult conflicts facing West Africa. As a result of the chieftaincy system, violent disputes often arise over deciding the succession of chieftains within tribes.

The system of chieftaincy is traditional in some regions but arose several centuries ago in other areas when the British regional colonial masters attempted to enforce a hierarchy similar to the northern Nigerian Muslim Caliphate on the tribes. They felt that a hierarchy would help them to disseminate their orders. Further, during the days of the slave raids, a weaker tribe would request the protection of a stronger leader, who would become their chieftain, serving as protector over the other. Today conflicts arise, often deadly, over who should be the chief of the tribe, such as in Bawku, a region in northern Ghana where Kanyog is frequently deployed.

Kanyog is grateful for the skills he is gaining in America and is living off campus with several other international graduate students, whom he describes as a "lovely group." Still, Kanyog misses the comforts of home and hasn't seen his family since he started school. Kanyog is currently working to get his family a computer with a camera so that he can video chat with his wife and children.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.