Three Musketeers

The Brandeis Theater Company strikes again for their second show in the 2007 to 2008 season with Alexander Dumas' Three Musketeers, performed by the Double Edge Theater Ensemble in Laurie Theater last weekend. Dumas' novel, adapted for the stage by Stacy Klein and Matthew Glassman is the adventurous tale of sworn alliances, revenge and true love, all proven to govern the impulses and rationality of mankind.The plot is a quite convoluted one, despite being a greatly shortened adaptation, and begins with an introduction to the mighty musketeers, a group of highly skilled, specially trained swordsmen, sworn to risk life and limb for the protection of their beloved king of England. They soon cross paths with the young and pugnacious D'Artagnan, who manages to anger each musketeer until they are driven to challenge him to three separate duels.

Their vendettas are thwarted, however, when guards from Cardinal Richelieu's regiment engage the fighters and force them to showcase their fighting skills. The musketeers, thoroughly impressed by D'Artagnan's abilities, entreat him to join their cause. Soon the four must embark on a quest to recover the queen's diamonds, which she foolishly gave away to her lover, the Duke of Buckingham. The diamonds are desperately needed for the ball that the conniving cardinal arranged for the specific purpose of embarrassing the diamondless queen. What ensues is an expedition rife with deception, betrayal and revenge in which, with a furious clanging of swords, the foursome battle for justice in the name of the king. You know the script-it's invigorating on paper. The quality variance of this play depends upon its execution.

The actors who played the musketeers did a respectable job. They didn't tend to lay on an outrageously thick air of nobility that might manifest itself in the form of megaphonelike vocal projection and overly conscientious syllabic articulation. Other, minor characters fell victim to this hyperbolic theatrical style, but that was not the musketeers' problem. The four men-all Theater Arts students-Robert Serrell (GRAD) '08, Anthony Stockard (GRAD) '08, Brian Weaver (GRAD) '08 and Matthew Crider (GRAD) '08-were largely believable and retained a sense of authenticity. If anything, they did not project and articulate enough, as most of their words could not be accurately comprehended.

Stockard (Porthos) was the only musketeer who upheld a perfect balance of volume and articulation and was almost always fully intelligible. Weaver (Aramis), though not quite up to par in this department, had an eccentrically cavalier style that actually increased the believability of his volatile character. However, other shortcomings among the musketeers existed in their swordfighting, which looked too contrived and choreographed. Up, down, up, down, swished their swords in a predictably repetitive manner, as their foes automatically ducked and lunged accordingly, adding a sense of triviality to the play's action sequences. Other than that and the unavoidably trite-sounding "All for one and one for all" proclamation at the end, the four protagonists performed commendable acting jobs.

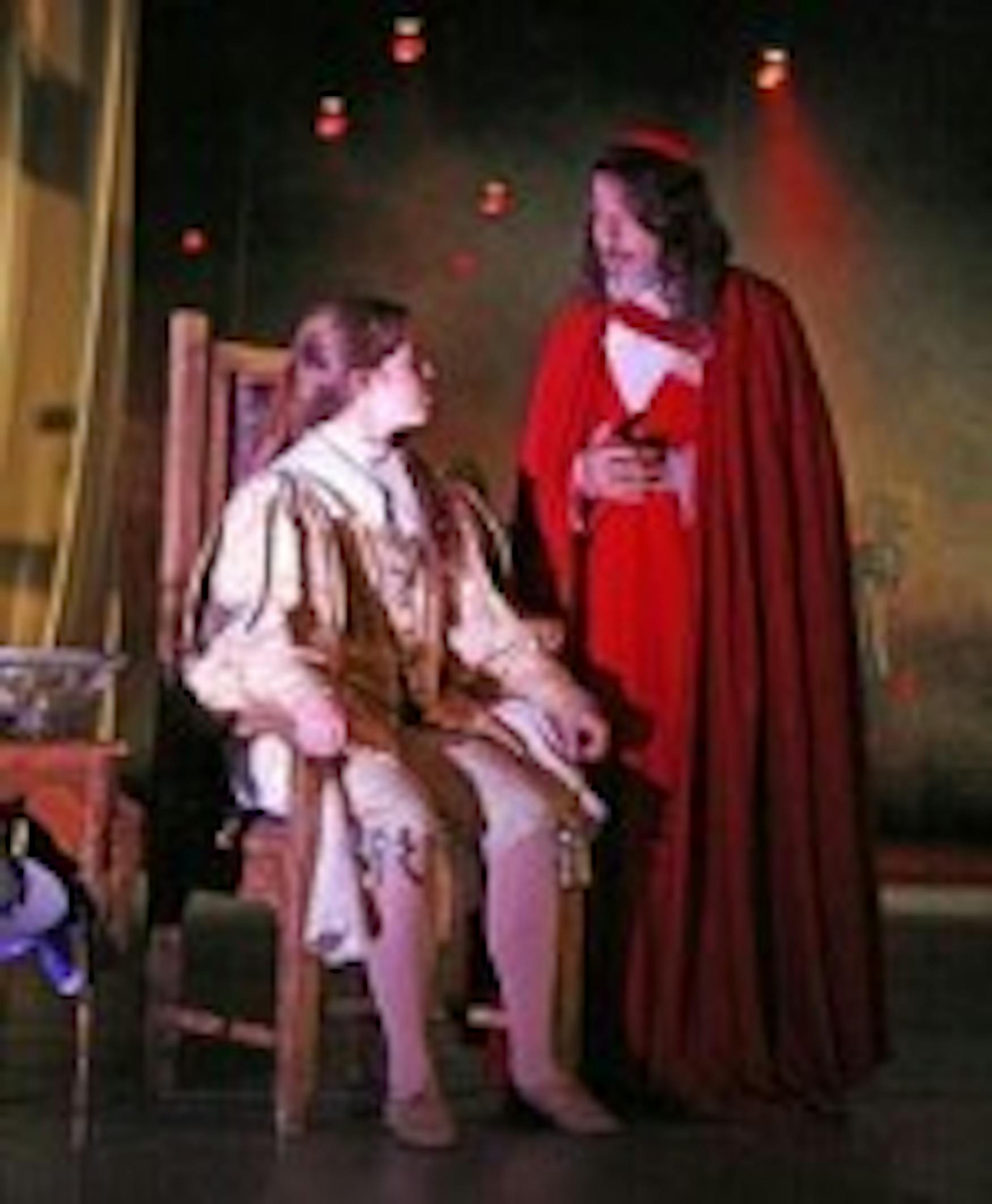

Even so, the most astounding actor in the performance was undoubtedly Carlos Uriona (GRAD) who played the scheming Richelieu. Malevolently floating across the stage in his blood-red robes, Uriona encapsulated the sinister cardinal, speaking with a Spanish accent that gave his evil utterances a gritty sense of authenticity. The same went for his swooning intonation, which caressingly hypnotized listeners. It was a job well-done for this theatrical veteran, no doubt the play's MVP.

But what was most impressive about the Brandeis Theater Company's adaptation, was the innovative set design and layout. The performance reversed audience members' conception of the conventional theater-viewing experience, as they were ushered into the center of the stage to watch the action unfurl around the perimeter of the room. Soon after, the curtains rolled up and the entire play moved from the original theater to an adjacent one. The audience moved with the performance and, as they crossed the between-stage threshold, actors welcomed us into the inn in which the next scene took place. Now the performers were utilizing two stages, which, as creative as this idea was, posed aural and visual problems relating to bodily obstructions and the distance of the actors with respect to the audience. Because most of the audience members had to stand while viewing, there was a good chance that the back of someone's head might obstruct the view. Additionally, as mentioned above, the musketeers did not project enough to be heard from the far stage, so much of the dialogue, and therefore the plot, was lost.

The audience was able to catch a break when they were ushered into seats for the last 20 minutes of the performance. It was then that viewers could fully appreciate the play as a dazzling spectacle. The costumes were acutely detailed, especially those made for the female characters, who donned sparkling dresses and ornate feathered masks. There was a costume moment in the play that escaped the realm of logic but knocked your eyes out anyway, when suddenly a 30-foot tall sparkling white gown with an actress perched on top made an appearance, slowly making its away around the stage and eerily towering over the events taking place below. This type of spectacle was commonplace in the performance, as acrobats, entirely independent of the plot, tumbled frequently and climbed ribbons flowing down from the ceiling.

BTC's adaptation of The Three Musketeers was a refreshing demonstration of out-of-the-box theater. It possessed an imagination that aroused intrigue and titillated the senses. However, it was clear that certain sacrifices, such as those pertaining to audience comprehension, had to be made in order to execute their creative vision fully. Overall though, it was an entertaining spectacle that called to question the basic banal conventions of the theater-going experience.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.