Find practical solutions to rampant grade inflation

Unedited Justice

Last December, I read an article about Harvard University's grade inflation in their school newspaper, the Harvard Crimson. According to the article, Harvard University Dean of Undergraduate Education Jay M. Harris released the median grade as an A- and the most received grade as an A.

I laughed. How silly was it that such a prestigious institution could have such low standards?

Last week, I picked up a copy of the Justice and saw an article titled, "Median fall grades released to the public." I grew excited at the chance to shove Brandeis' higher academic standards in Harvard's face. According to the article, however, Brandeis students received a median grade of an A- and maintain an average grade point average of a 3.4.

I was ashamed and humiliated. All of my pride about working hard in classes to achieve high grades began to dissipate; what did this mean for me as a student? Did this mean that I was taking easy classes and that my grades simply reflected that? Brandeis Senior Vice President for Communications Ellen de Graffenreid defended Brandeis' grade inflation by stating, "The averages and the distributions have been remarkably stable over time, which would not indicate a pattern of grade inflation."

Are we supposed to feel better that grades have always been inflated and that this isn't simply a recent trend? To make matters worse, she later added, "The averages at Brandeis are consistent with those at other elite colleges and universities."

Adapting the old "If you can't beat them join them" ideology is not permissible. Rather than conform to the norm, we should be setting new trends and maintaining non-inflated grades.

Some might offer that everyone receiving high grades simply means that everyone is just doing really well in their classes. But this is incorrect. A high median grade simply indicates that grades have lost value as an intellectual currency. Best put by Syndrome, the evil villain of Disney's The Incredibles, "When everyone's super, no one will be."

There are valid arguments as to why grades shouldn't exist in the first place: they cause competition in an area where some believe competition isn't necessary, they don't always accurately represent what people actually know and they often yield bias to those who test well, among other reasons. But those arguments are irrelevant because, whether we agree with them or not, grades are currently the main metric by which students are evaluated. Grades are weighed heavily on applications for internships, graduate schools and even jobs.

It is concerning to think that we would be disadvantaging our students by issuing comparatively lower grades than other universities. However, if we come out publicly in strong opposition to grade inflation, and call out other elite institutions on their grade inflation, the issue will become more well-known among employers and recruiters, and the issue as a whole can begin to be solved. It's the other schools, not us, who will be disadvantaged.Additionally, Brandeis could even distribute "adjusted for inflation" grades which compare current Brandeis grades against the school's past inflated standards, or against a national average. This would map the C a student might receive against the A- they might have received before Brandeis became conscious of the issue. Rather than passively accepting the standard around grades as a necessary evil, we need to correct it through leading by example.

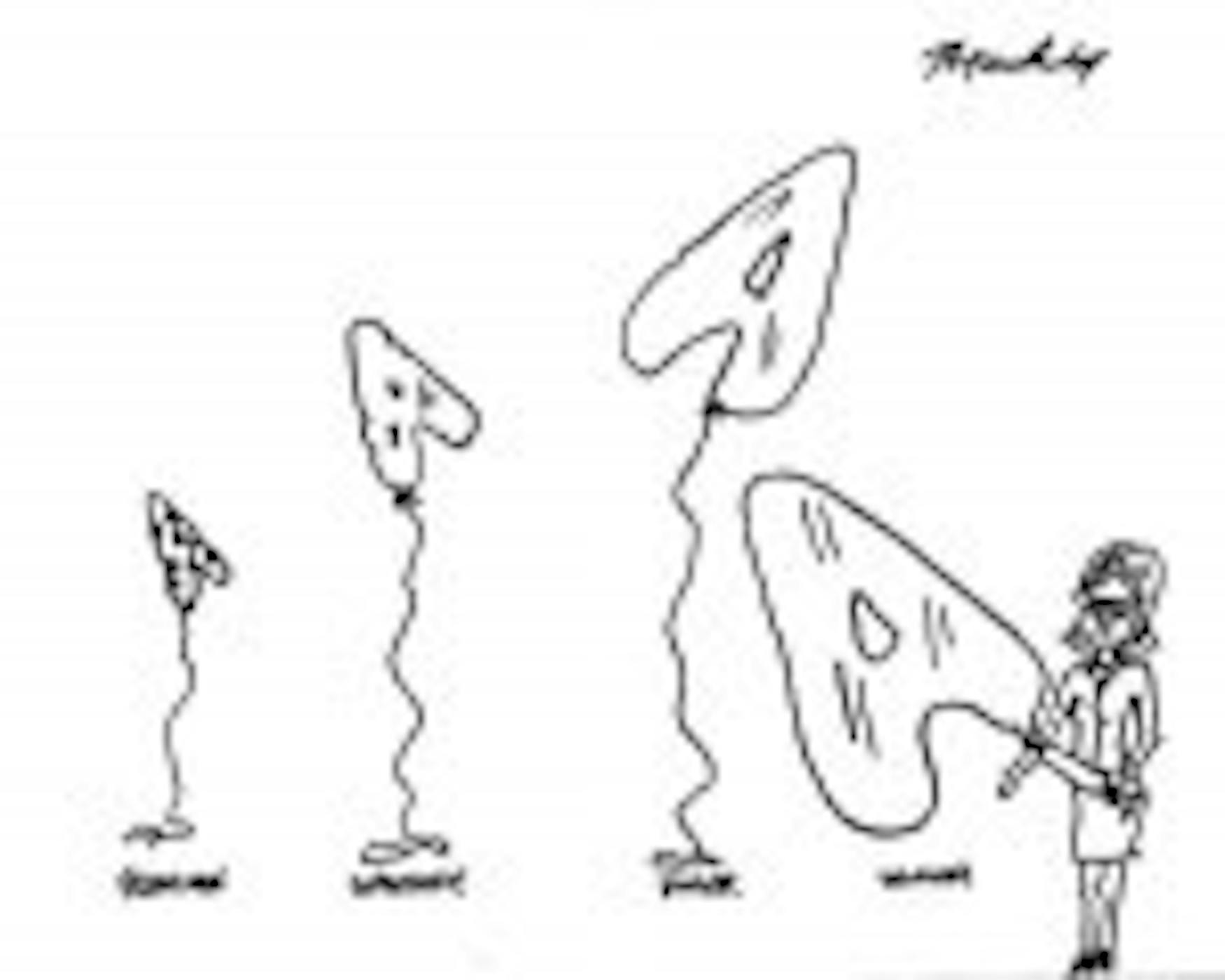

Grade inflation also provides a ceiling for learning-a point at which one becomes complacent with his or her current progress. This is ironic since one of the original purposes of academic assessments was to provide a floor for the basis of knowledge that someone should possess. For example, when lifting weights, you don't set a finite goal of 100 pounds, then reach it and stay there. You constantly increment the weight once your current weight becomes too easy. The process never ends; it's simply revised at each iteration.

If an A- or A is easy to reach, students are able to stop working once they've reached it. And why should this ever be a lesson educators encourage? Learning has no definite starts or stops. But providing an easy-to-reach maximum grade perpetuates the falsehood that it does.

As educators, as students, as lovers of learning, we need to hold ourselves to higher grading standards.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.