Artist engages with forms of femininity

As a young girl growing up in the 1950s, artist Christina Ramberg developed a preoccupation with gender roles and the female form, but her untimely death at the age of 49 hindered the spread of her work. Jenelle Porter, a senior curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, has assembled a concise but eye-opening exhibition of the works of the Chicago artist whose work from the years 1971 to 1981 reveals a maturing study of form and shape.

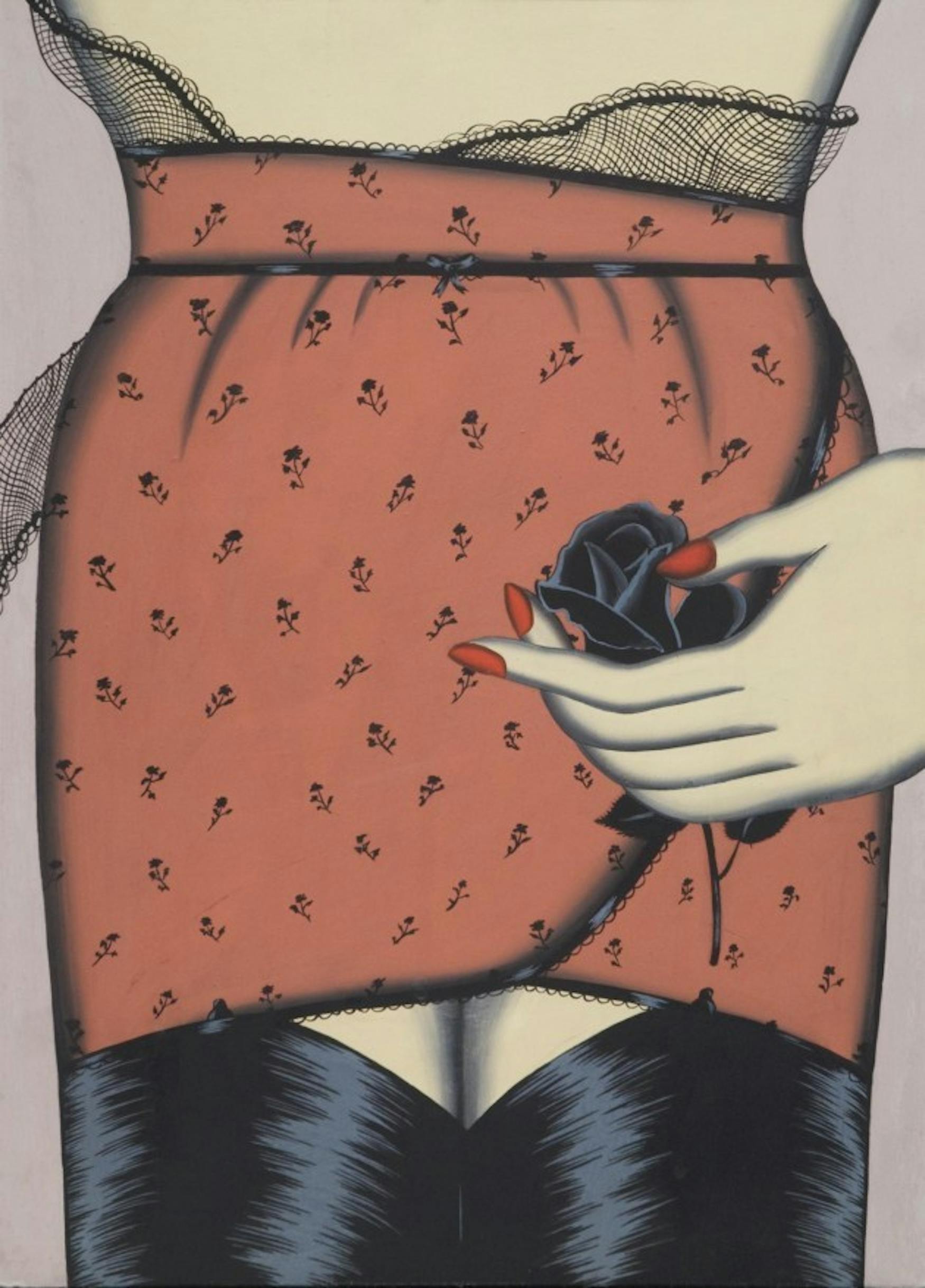

Ramberg's paintings present clear shapes and forms of women's bodies as the women slip their dresses up and over their bodies. The artist chooses to paint only a microcosmic view of the female body. She starts painting at the neck and ends mid-thigh in a somber color palette that appears to connote a Victorian vibe.

Her 1971 canvases "Black Widow" and "Shadow Panel" reference the Western art historical trend, epitomized by the Impressionist artist Degas, of depicting women in the intimate moments of their lives. Ramberg is not painting the soft, delicate toilette scenes of Degas, though-while both Ramberg and Degas rarely depict the faces of their subjects, their implications are different. Degas' anonymous women increase self-identification between the viewer and the woman in the work, whereas the women of Ramberg's works, whose heads are sharply cut off by the frame of the work, appear robotic. Utilizing geometric figurations, Ramberg paints the female body as an assemblage of different parts that are then amalgamated to create one whole. Her early work composes the female body rather concretely as the curve of her subjects' bosoms seamlessly attaches to a rectangular mid-section. Yet, the body is not nude; instead, feminine fabrics and motifs such as lace, ribbons and floral embellishments emphasize form in the way that lingerie and undergarments are used to suck, tuck and more importantly, bind the female body into societal norms of perfection.

As time progressed, Ramberg's style evolved from concrete figuration to an abstraction of form as she uses paint to evoke different textures and fabrics that she uses in place of the body. These images are darker-grotesque, even-as they do not depict the idealized female form. For example, Ramberg's "Wired," completed between 1974 and 1975, creates a headless, insect-like entity with pincers for arms that are composed of squiggles of wire and meticulously-bound strands of hair that tightly bind and constrict the pelvic area. While the image implies an animalistic depiction of the original, it is also indicative of female sexual organs.

On one hand, Ramberg pronounces the similarities between human and animal form. On the other hand, she utilizes fabric to highlight the body not through flesh but instead through cloth and texture. The body becomes mutable as in the 1977 work "Schizophrenic Discovery," in which Ramberg creates the form of the body through thick, rope-like strands of what appears to be hair, clothing and visible undergarments. Alluding to the piece's name, the combination of diverse materials reflects a schizophrenic nature that also works to allude to the increase in mental and emotional dismay in women during the 1950s and '60s as they attempted to adjust and conform to changing societal expectations. A tiered, steel-blue, collared shirt covers the left half of the body in exacting strokes that contrast the right half of the body, which has no visible signs of a shirt with the exception of the pointy collar. Instead, broken strands are haphazardly composed to evoke a sense of shape. In this broken, imperfect depiction of the female form one cannot help but ask: what is it, what ingredients, are needed to be a female?

As an artist associated with the Chicago Imagists, Ramberg combined her art and cultural influences to produce a body of work that not only grappled with cultural issues of gender politics and constructions but also artistic concerns of form and shape. The Christina Ramberg exhibition at the ICA shines light on an artist who chose to contest the use of the female body as a vessel not just historically, but also socially.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.