Keaton reminds us to revisit the silent film era

Theaters these days are full of fast-paced movies with modern filmmaking techniques and complex story structures, but sometimes one needs to step on the brakes and go back almost a century to the films that introduced these practices we now take for granted. One must return to the golden age of cinema, to the Hollywood of the late 1920s to early 1960s. So, amid the oncoming onslaught of summer blockbusters which seems to come to theaters earlier and earlier every year (I’m looking at you “Black Panther,” “Tomb Raider” and “Pacific Rim: Uprising”), it seemed just to attend an on-campus screening of a Buster Keaton film.

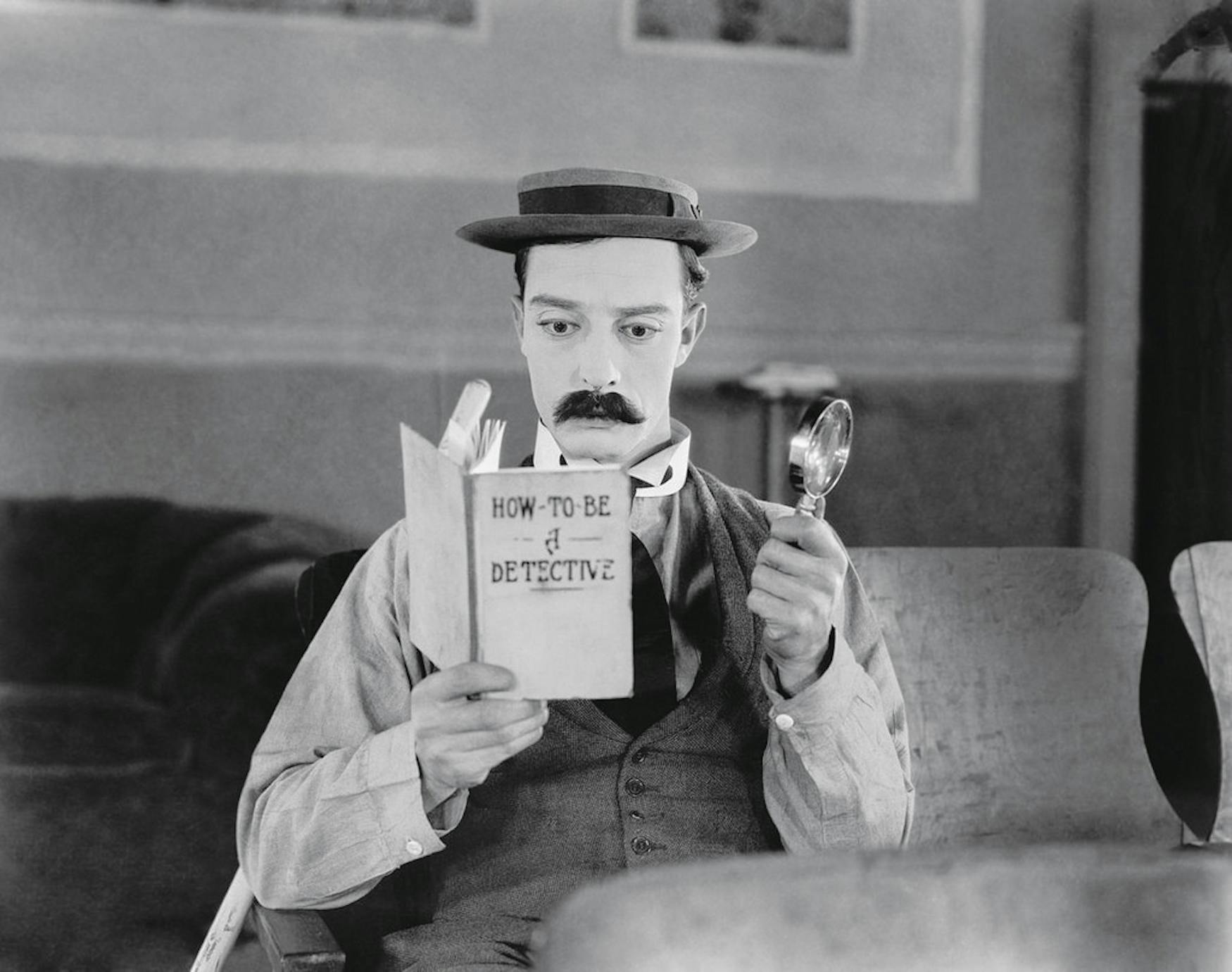

The screening of the 1924 film “Sherlock Jr.” was hosted by the History of Ideas program. The organizer, academic administrator Julie Seeger (PHIL), invited students and faculty to “A Night at the Movies,” one in a series of three movie nights throughout the semester. This first one was, in part, also a celebration of Prof. John Plotz’s (ENG) new book, “Semi-Detached: The Aesthetics of Virtual Experience since Dickens.”

The English professor’s opening remarks brought up themes of inaccessibility to cognitive space and sharing worlds between dreams and reality. Plotz drew parallels between the Keaton film and the boldness of “The Musicians,” a 1595 Caravaggio painting. He explained that both media of art convey an aesthetic experience the audience can only observe from a distance; that we can understand what goes on, but we cannot say that we understand the rules of that reality. The musician in the painting acknowledges the audience with direct eye contact, but with the blank stare of a man tuning his guitar and prioritizing the improving sound of his instrument over his other senses. We, as the audience, are in the room with him, and yet he does not recognize us with a true gaze of acknowledgement.

Keaton similarly introduces his dreams to us in “Sherlock Jr.,” aware he is sharing the world his character inhabits. The film is the first of many to incorporate metafiction (which some might just refer to this as “meta”), the way in which a story acknowledges that it is a piece of fiction and is purposefully self-referential. Keaton’s story-within-a-story via his character’s dream is meta. He warps the film’s story and characters, hoping the unjust accusations thrust upon him are exposed and that he gets the girl of his dreams (in both ways, I suppose).

“Sherlock Jr.” is an easily consumable joy to watch. The silence of the film makes way for an elegant and sprightly soundtrack. You have an opportunity to behold a visual style you don’t get anymore, one of universally beloved slapstick comedy infused with dangerous stunts you wouldn’t see most actors do today. You can’t see Adam Sandler sit on the coupling rod of a steam locomotive or Seth Rogen on the cowcatcher of a train like Buster Keaton did in “The General” (1926).

“Sherlock Jr.” featured visual effects that are impressive to this day, especially during a dream sequence with changing backgrounds. The stunts are not only impressive and funny but also add a sense of anxiety. You know Keaton is doing them all himself in set pieces that are introducing danger that promises injury, but he ventures forward with tenacity and commitment. Though “Sherlock Jr.” doesn’t feature anything as dangerous as his famous “falling house” stunt of “Steamboat Billy Jr.” or anything atop the train like in “The General,” Keaton still delivers.

I suggest you all avoid bombastic and CGI-filled movies for a time. Go back to the silent era. There isn’t much to see in theaters other than Oscar nominees building momentum and buzz with general audiences and academy voters. Enjoy some of the classics. Revert to the black and white. I spent my weekend returning to “The General” and some works by Charlie Chaplin. I recommend “City Lights” and “Modern Times,” but if you want to be stirred by some fantastic dialogue, watch “The Great Dictator.” If you want to be inspired, watch it. If you want to be hopeful in our time, watch it. If you want to be assured that evil will never win, watch it. For those of you who know which monologue I am referring to, I implore you to revisit it. I still get goosebumps. Films like these demand more attention; we can’t all only love “Casablanca,” “Citizen Kane” and “The Wizard of Oz.” We must reflect on the pioneering work of the cinema giants that were Keaton and Chaplin.

All of these feelings were stirred up and brought back thanks to the History of Ideas program. The series’ follow-up feature, “Human Flow,” is a documentary by renowned director Ai WeiWei. In the feature, a crew travels to 23 different countries to document the forced displacement and migration of refugees throughout the world. Though I am unaware of the date for this screening, I hope that you all make time to see it. It’s events like these that make me wish the Wasserman Cinematheque at the Brandeis International Business School was used regularly to screen these important films.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.