Recognize the negative consequences of online anonymity

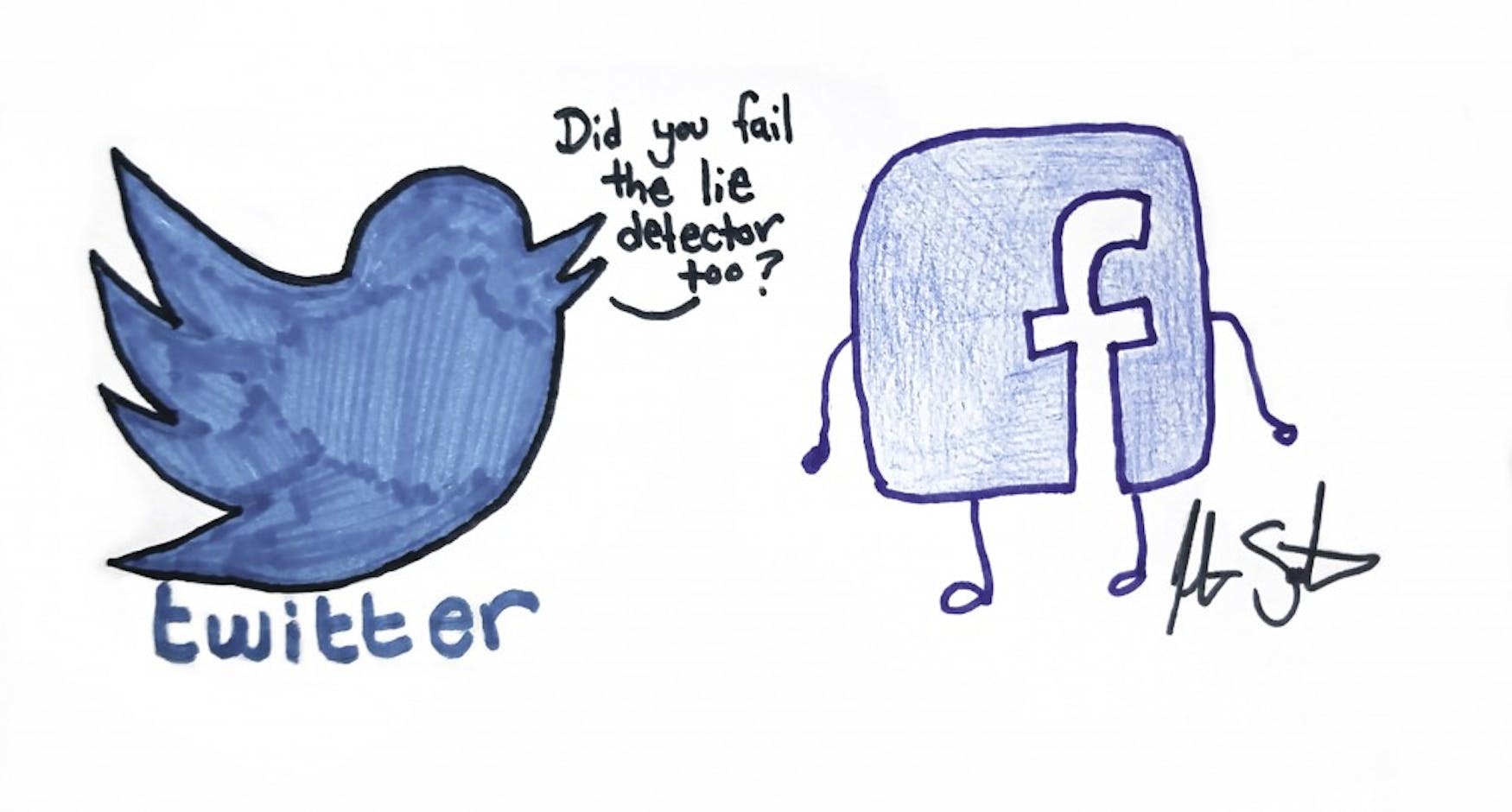

In 2017, who is a person? Our online persona, rather than public records, define our identities, and the internet is an unregulated space where people falsify their identities for their own nefarious purposes. A Sept. 7 New York Times article exposed new details of the Russian influence on the 2016 presidential election — specifically, how Russians created several hundred inauthentic Facebook and Twitter accounts which “spread anti-Clinton messages and promoted the hacked material leaked.” These accounts posed as individuals and “friended” real people in hopes of influencing them with these shared posts. According to a Sept. 6 New York Times article, these fake accounts also purchased over $100,000 in ads targeting divisive social issues such as immigration and gay rights. They did all this under aliases such as “Melvin Redick,” which did not exist in the public records of their states.

In a bizarre twist, Russian influencers acted out a sinister episode of “Catfish.” If your appetite for reality television is not as ravenous as the average American’s, “Catfish” is a show where online couples who have never met in person are brought together for the first time. Premiering in 2012, the show developed a cult following — not because of any discoveries of true love, but rather because it exposed widespread deception and captivated audiences. It was only a matter of time before the ease and anonymity of social media was manipulated for political gain rather than for dating.

Of course, lying on the internet is nothing new. For a time, every American with an email account was related to a Nigerian prince who was just dying to give them one million dollars — a scam that has existed since the mid 1990s, according to a May 19, 2013 Boston Globe article. The more naïve among us may have hesitated before clicking “delete.” Today, “don’t believe everything you hear on the internet” is common knowledge — passed on to children as the modern equivalent of “don’t talk to strangers.” A poorly worded email, without any evidence or photographs that asked the recipient to believe a practical fairy tale and hand over routing numbers. Come on.

There is no identity test on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram. Users need only an email address — free and simple to create itself — to open an account. This lends the sites a democratic nature, with relatively low barriers to entry. The flip side of this is that there is no test of legitimacy. In a step toward ensuring authenticity, the three platforms have begun offering “verified user” programs, in which users can request to submit identifying information to the network and meet with a representative to confirm their identity. However, the service is limited to accounts “determined to be of public interest,” according to Twitter’s Verification FAQ. This determination is made by Twitter. As of Sept. 9 of this year, Twitter verified 278,000 accounts, out of 328 million monthly active users, according to their most recent quarterly results.

But the line between real and fake has blurred so fast that fake Instagram stars can amass thousands of followers without the hassle of a pulse. Case in point: Instagram “model” “Lil Miquela” generated controversy as fans tried to work out whether she was a real person or a computer-generated image; the general consensus is that she’s a hybrid of photographs and 3D imaging, according to a September 2016 report from Independent. However, her actual identity does not matter to her 277,000 Instagram followers who propelled her music to two million plays on Spotify. Of course, this example seems rather silly, as a CGI model is hardly seen as a serious political figure. Yet Lil Miquela has expressed various — mostly socially liberal — political stances, according to an Aug. 17 Vogue article, and this establishes a dangerous precedent. As the 2016 election demonstrated, we live in a post-factual era of American politics. We value conviction over reality. It seems that America might make room in the political landscape for influencers who strike an emotional chord — their actual identities immaterial.

According to the same New York Times article, fictional Melvin Redick, complete with “photos borrowed from an unsuspecting Brazilian,” made history as “among the first public signs of an unprecedented foreign intervention in American democracy.” The Russian imitators of the 2016 election have exposed a weakness in our reality. According to the Office for the Victims of Crime, identity theft is classified as “fraud and related activity in connection with identification documents.” However, written in 1998, the Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act failed to account for online identities, and the creation of a false persona which purports to be real but does not imitate a specific individual falls into a legal gray area. Increased regulation and policing towards online identity assumption would protect people from imposters but would not necessarily deter efforts like those of the Russians. Perhaps legislators should focus on the process of opening social accounts. After all, they are used for organizing, commerce and much of modern communication. For those envisioning a ‘Facebook DMV’ or thinking of onerous voter I.D. laws, rest assured, a simple video call with a representative to ensure that the account owner is a real person who roughly matches the uploaded photos would suffice. Social networks, in conjunction with municipalities, could launch ‘activation stations’ where anyone could come and use a webcam for free to make this call, in case one was not available at home. The openness of the internet is its greatest attribute, and everyone is better off when we are not getting Catfished.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.