WWI propaganda on display in Goldfarb

If you have ever wandered past the small, glass-encased room on the second floor of the Goldfarb Library, you will have passed by an exhibit hosted by either the Robert D. Farber Special Collections or the University Archives. The two take turns hosting these exhibits, all based on materials in the University’s collections. The exhibits have spanned topics ranging from the early days of music at the University to dime novels.

When, a few months ago, it was the Special Collections’ turn to host an exhibit, the Special Exhibits staff looked to their collection of propaganda from World War I for their current exhibit, Patriotism + Propaganda: Poster Art in World War I America. The theme is timely—we are currently in the midst of the centennial years of the First World War. And luckily, Special Collections, which holds rare materials unrelated to the school compared to the University Archives, has almost 80 such artifacts in its collection.

Surella Seelig, Archives and Special Collections Coordinator, one of the two curators of the exhibit, said in an email to the Justice that in choosing what to feature in these exhibits, curators consider “what will be visually and intellectually interesting to our visitors, and what can be exhibited in such a way as to do justice to the materials without endangering them.”

This particular exhibit does not feature the actual works, as Seelig says is common for their exhibits due to the fragility of the objects. Rather, it features color copies of the works.

The exhibit featured a variety of different posters, all divided by their message and audience. There were the classic “I want you” posters on display, soliciting young men to join the army. But there were also posters calling for a variety of other ways to help the war effort without actually going to the front lines, including posters asking citizens to buy war bonds and ration food. The wall text at the enterence to the exhibit alluded to this diversity of the war experience, noting how these posters evoked a sense that a person could be as much of a hero at home as overseas.

The exhibit notes that the most common pieces of propaganda were those urging men to enlist, but the second most common were the propaganda asking Americans to invest in the war effort. There were quite a lot of posters on display asking for people to buy bonds. One fairly direct piece is emblazoned with a blue V on a red background, which, underneath, reads “INVEST.” Another evokes a religious sense of duty. It reads: “THAT LIBERTY SHALL NOT PERISH FROM THE EARTH BUY BONDS.”

“We were interested in trying to understand both the overt and the more subtle messaging that was going on in these posters,” Seelig wrote.

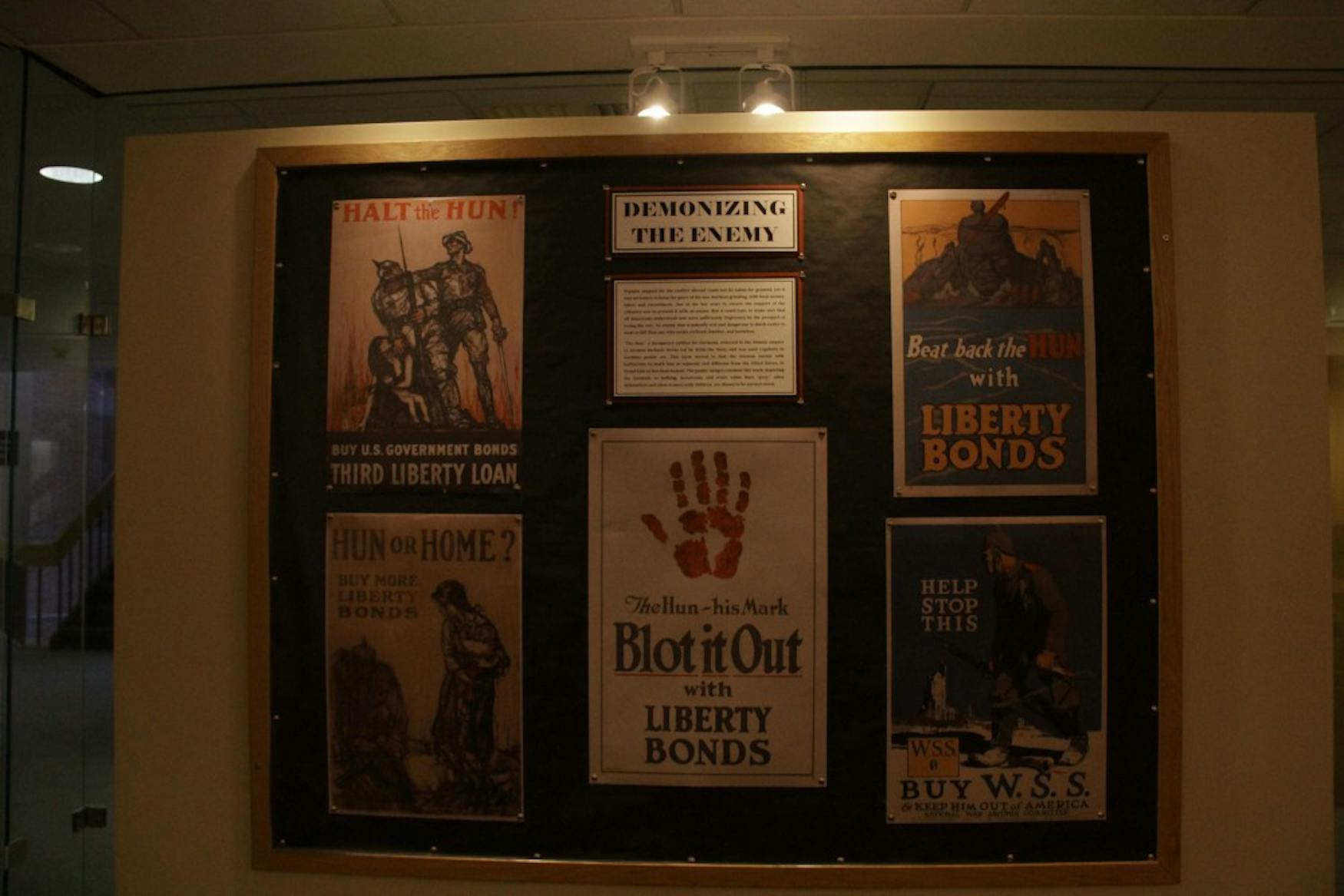

There were also posters meant to evoke a hostile attitude toward the German enemy. One poster presents a large, dark and looming figure, representing a German. The enemies were called “Huns,” as the note says, in order to link the Germans to barbarism. The poster mimics the emotional hostility of the war in order to raise funds. It reads, “Beat the HUN WITH LIBERTY BONDS.” Another, that portrays a red handprint, reads, “The Hun—his Mark Blot it Out with Liberty Bonds.”

The posters are clearly intensely thought-out and rhetorically provocative. One such piece of propaganda, sponsored by the Food and Drug Administration, quoted President Abraham Lincoln, seemingly as a way to evoke a sense of patriotism and nostalgia for America’s history.

When asked about what she would like to see the audience take away from the exhibit, Seelig said that she would like it to remind the University community that the Robert D. Farber Special Collections or the University Archives actually house these rare materials, which are open to the public. The collection is also digitized for the community to see even when the exhibit is not on view.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.