Sorensen Fellows spend summer working on community building projects

If you could spend a summer working anywhere in the world on a project that promotes social justice with the organization of your choice, how would you even begin to decide what to do? What if the deal got a bit more interesting—let's say you would be backed by a community of peers and ethics experts and you'd receive up to $4,000 to finance your dream?

Every year, a new cohort of Sorensen fellows have the privilege of answering that question, and better yet, seeing their answers realized in a matter of months.

“I worked in business development with very, very small businesses in Nairobi, in a neighborhood called Kibera, which was termed the second-biggest slum in Africa,” Shimon Mazor '16, one of last year's Sorensen fellows, told the Justice. “I was never in Africa, and I was really interested in going.”

Mazor worked with an organization called Kenya Social Ventures, he explained, which partners with smaller organizations in the area to help out with a variety of struggles, like fundraising. Many of the partner organizations the Kenya Social Ventures aids, he said, are organizations like schools. Mazor ended up working with a slew of organizations this way—he helped a small primary school with budget planning and fund raising and worked with an organization called Power Women Group that seeks economic empowerment for women who carry the HIV virus.

“These women work together to create jewelry, to create all kinds of arts and crafts, and they sell it to tourists,” he said. The organization helped the women transition their earnings into more marketable skills, and even their own businesses. “They opened a small hairdressery, or salon, for women to start learning that craft. … We're talking about in the slums; this is all happening within the community.”

“This is a whole mechanism to really promote their inclusion in society and their finding work,” he said. He explained that because the local government views the people who live in Kitera as being there “illegally,” since it is a slum, it's not unusual for the government to try to drive the people out—making work that helps equip locals with skills and support for financial independence that much more important.

Mazor worked with a third organization, Victorious Bones Craft, which takes recycled animal bone, often bought from local butchers, and makes beautiful products from it. “There's a lot of bone workers in these kinds of areas, … hundreds of people who are doing these kinds of things.” He spent time with a group that helped the bone workers improve their marketing strategies, and helped raise awareness about the working conditions of the bone workers among charitable groups in the area.

The Sorensen Fellowship is run through the International Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life at Brandeis. Named for Theodore C. Sorensen, the founding chair of the center's International Advisory Board, the fellowship “seeks to engage Brandeis undergraduates with constructive social change on the international stage” as a tribute to Sorensen's commitment to public service, according to the program's website.

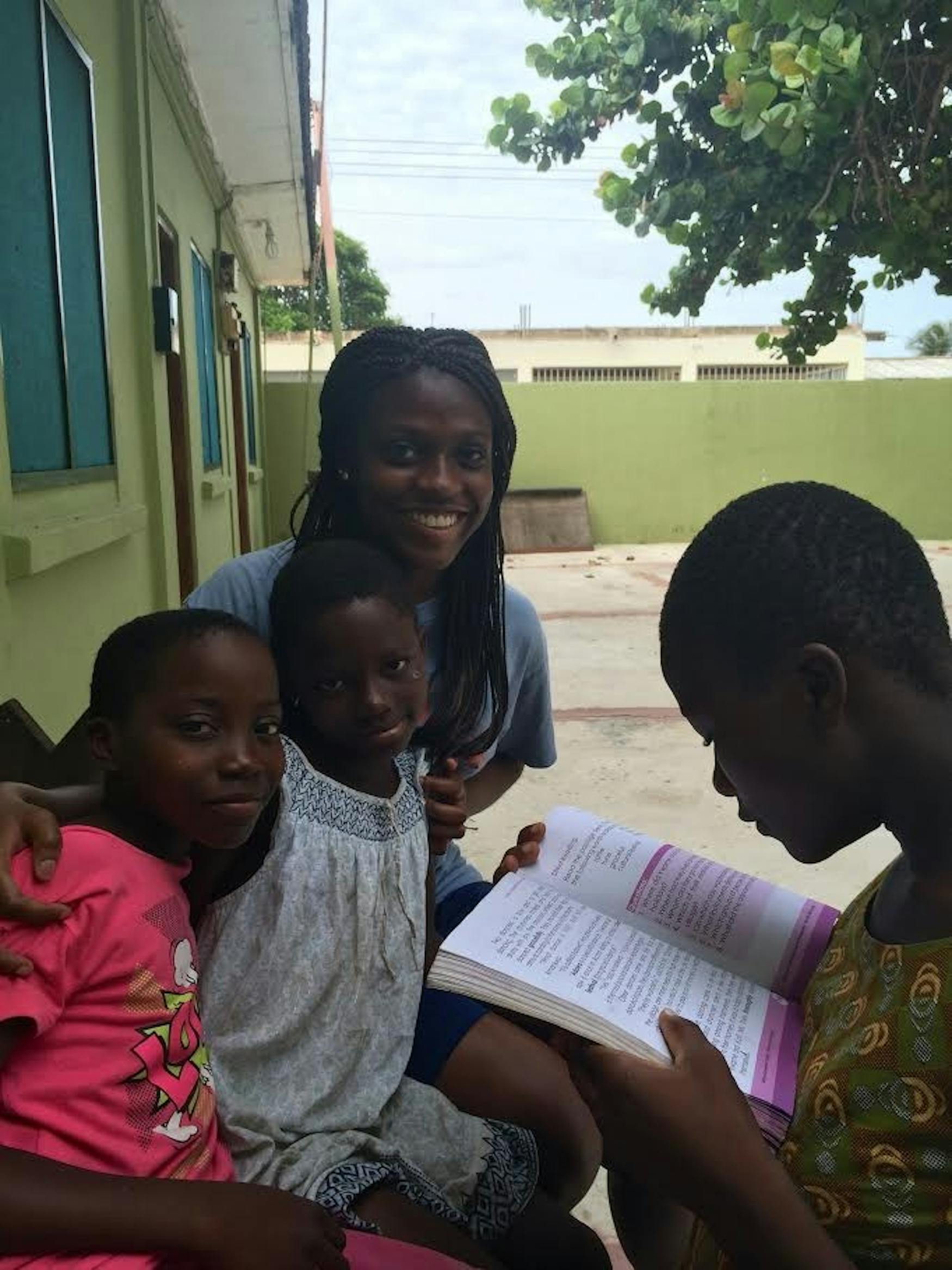

Ngobitak Ndiwane '15, another recipient of the fellowship last year, also spent her summer working in Africa. Ndiwane worked with Atorkor Development Foundation, which is in Atorkor, Ghana—a small, seaside village community in the southeastern part of Ghana.

“I was teaching public health at elementary and high schools,” Ndiwane said. “We would teach a different topic every week. For example, one week would be oral health, the next week would be nutrition, exercise and anatomy.” As a Health, Science, Society and Policy major, Ndiwane said that she expected some of her coursework at Brandeis to transfer to her teaching but was surprised that some of the things she finds intuitive about health were not so for her students.

“We adjusted the lesson plans to the different age groups we were teaching,” she said, “because the students ranged in age from four or five to 24, because some students had to take years off of school for various financial reasons.”

In addition to teaching at the schools, Ndiwane also interned at the local medical center. There, she said, “my job would be to take the blood pressures, weights and temperatures of adults and children who would come.” She worked with another intern to conduct a community health assessment, going door-to-door to collect demographic health information. “We took surveys to the villagers so that they could fill them out, and we also took blood pressure at the same time. This was all done so that we could record it, and then give the information to the health center... so that the staff could follow up with different households or members of households who were at risk for different chronic illnesses.”

Last year, along with Mazor and Ndiwane, the recipients of the fellowship included Ibrihima Diaboula '16, Elad Mehl '16, Sneha Walia '15 and Shane Weitzman '16. The students applied before winter break last school year and prepared for their summer internship experiences by taking specially-chosen courses in the spring. After coming back from their summer internships, this fall semester, the fellows all took a course together, focusing on reflecting and writing about their summer experiences.

Gathering together all that they've learned, the fellows' writings about their programs are combined into a publication each year, released by the Ethics Center. This year's publication was appropriately titled From Looking to Bear Witness.

“Once the papers were completed,” Cynthia Cohen, the director of the Program in Peacebuilding and the Arts wrote in an introduction to the publication, “the class discovered a common theme: the importance of building trusting relationships in order to facilitate transformations of the kind required for personal growth and for community development.”

“Going in, I knew that I was going to teach, but I already suspected that I would be the one who would learn the most out of the experience,” Ndiwane said. “Just getting to be with a different community and having them accept me—by learning more about them, … I was still able to learn so much about myself.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.